Congress Members From Obese States Question the USDA's Dietary Advice

Our fattest states' representatives don't seem to think so.

Outrage surrounding the proposed U.S. Dietary Guidelines hit the floor of Congress today as pols peppered top government officials with criticisms. Though the discussion was about health, feedback largely pertained to the wellness of agricultural and processing industries.

Health and Human Services Secretary Sylvia Burwell and Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack soaked in barbs from members of the House over an advisory report, published in February by the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee. While its core recommendations aren’t unusual — suggesting a diet that’s heavy on fruits and vegetables and light on red meat and sugar — its guidelines on the overall makeup of our diets raised specific concerns in specific states.

Representative Mike Rogers of Alabama (the fifth-fattest state), defended food production in his district and criticized the advisory report’s recommendation that Americans maybe consider eating less red meat.

“Wouldn’t red meat be part of a list of things you should eat, as long as you eat lean?” asked Rogers.

“It is,” replied Vilsack.

“I’m sorry, I thought you said you should put it in a list of things not to eat.”

“Sir, what I said was, if you’re concerned about over-consumption of food, generally, then obviously you’re going to suggest that people should eat less of something they are eating a lot of,” Vilsack explained. “That’s the key.”

It went on like that for a while.

Vilsack talking Congress off the ledge.

Other representatives suggested the DGAC’s review of the science wasn’t thorough enough. Concerned that low-calorie sweeteners weren’t recommended in the guidelines to help combat obesity, Representative David Scott, a Democrat from Georgia (which claims the 19th-highest obesity rate), cited a study showing they could lower “adiposity” and asked why, like so many other studies, it wasn’t considered in the report.

If a Dietary Guidelines assessment is going to happen every five years, Vilsack explained, there will inevitably be a cutoff for the papers that can be considered. But more than 4,000 papers were considered by the DGAC, he said, and it would be “unfair to the committee and unfair to the process to suggest that we’re not looking at the science.”

Representatives appeared to be confused about the difference between the Advisory Report, which is meant to advise the federal government — and the official Dietary Guidelines themselves, which have not yet been finalized. A significant part of the hearing was dedicated to explaining this difference.

But what about the candy bars though?

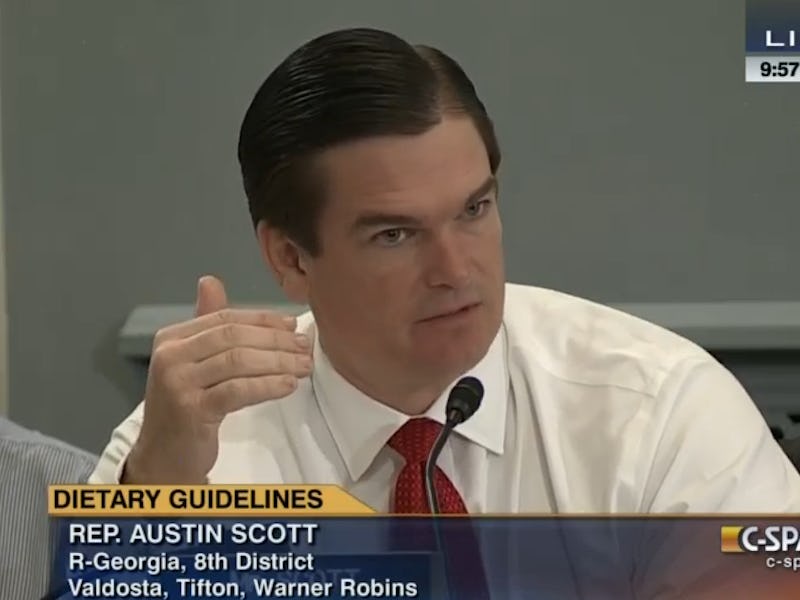

“There’s a belief that the people on the committee entered with a bias, and we’re searching for the science,” said Austin Scott, a Republican from Georgia (a state that’s generally unhealthier than 31 others, who later read a text from a Dad:

“They’re being told they can’t sell candy bars to raise money,” said Scott, with a straight face.

“Folks can sell outside of school, which is what these candy deals are,” Vilsack said, also with a straight face.

It’s understandable that the American public might be losing trust in the USDA’s guidelines, as Representative Collin Peterson of Minnesota (which has the 36th highest obesity rate, if you were wondering) suggested during the hearing. When recommendations change drastically from one year to the other, it’s hard to know what to believe.

Burwell

But the point Burwell and Vilsack consistently drove home with not an insignificant amount of patience was that science evolves — and the recommendations have to change with it.

“It is essential that the guidance that comes out of this process can be trusted by the American people,” said Republican Michael Conaway, Chairman of the Committee. (He’s from Texas, home of the 11th highest obesity rate.) He’s right — but the American people need to trust the people developing the guidance first.