Nobel Prize in Physics Awarded to Neutrino Hunters

These are the guys that found out neutrinos are shapeshifters.

Ask a member of the public what a neutrino is or what they’re good for, and you’ll probably get a blank stare. But any physicist can tell you that the tiny, neutrally-charged particles have some big implications for the universe.

A pair of physicists — Takaaki Kajita from the University of Tokyo and Arthur B. McDonald of Queen’s University in Kingston, Ontario — were jointly awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics on Tuesday for their work in neutrinos. Kajita and McDonald both discovered that neutrinos are able to change identities, and in order to do so, they must possess mass — contrasting with previous conclusions about them.

Let’s back up here a moment and get some background information out there: Neutrinos are the second most abundant particles in the universe. They are everywhere, drifting around the universe at near the speed of light since the Big Bang, and also being created by nuclear reactions and radioactive decay.

Yet for more than 80 years, physicists have only had a glib understanding of how they worked. They carry no electric charge, and don’t play a very conspicuous role in the many physical interactions — barely interacting with matter. It wasn’t even until 1956 that neutrinos were actually confirmed to exist.

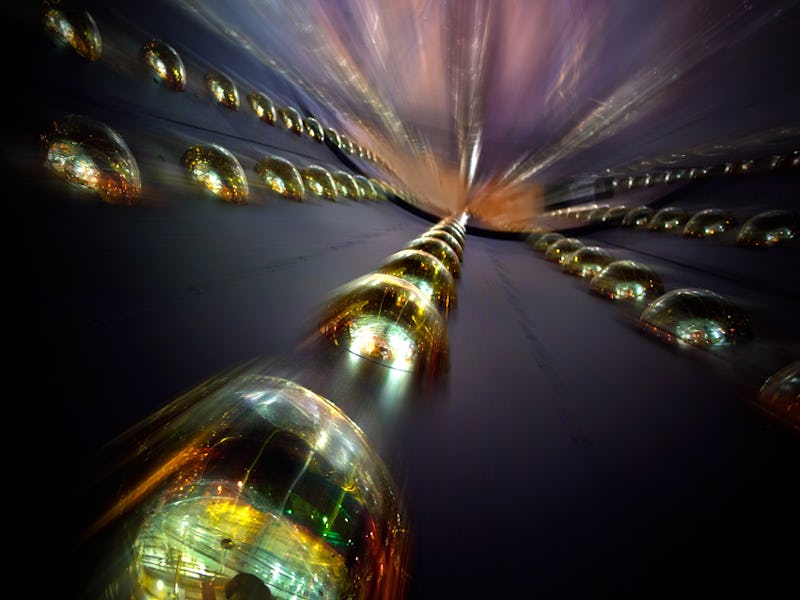

Collectively, Kajita and McDonald demonstrated that neutrinos can flip back and forth between three different “flavors.” Katie was able to demonstrate this in 1998, when an experiment conducted by him and his colleagues showed neutrinos flipping between two identities while en route to the Super-Kamiokande detector (3,300 feet underground).

The three flavors are referred to as muon, tau, and electron. Yum.

Meanwhile, in 1999, McDonald and his team found a third identity of neutrinos that were traveling from the Sun toward the Earth, using a new detector underground at the Sudbury Neutrino Observatory in Kingston, Ontario. That detector is 6,8000 feet underground.

The new discovery has already helped cosmologists understand more about the universe and its origins. Many have already started building on the research in hopes of learning how the sun works and moving forward with developing and perfecting fusion reactors.

“The discovery has changed our understanding of the innermost workings of matter and can prove crucial to our view of the universe,” said the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences in a statement posted on their website.

The winners get to split the $960,000 prize, along with the bragging rights of course. In a news conference at the University of Tokyo, Kajita told the audience he wanted “to thank the neutrinos, of course.”