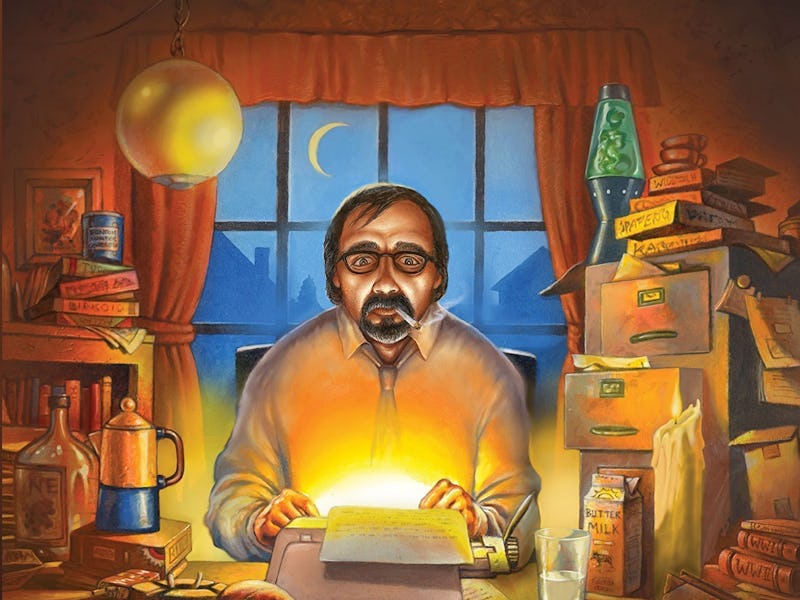

How Dungeon and Dragons Creator Gary Gygax's Leveled-Up the Real World

The story of the storyteller behind the greatest role playing-game of our time.

Gary Gygax has touched your life, even if you don’t know who he is or you’ve never rolled a saving throw. Gygax created that role-playing game to rule them all, Dungeons and Dragons. Author Michael Witwer, whose biography on Gygax, “The Empire of Imagination” hits shelves Tuesday, sees the legendary game designer’s influence not only in those dungeons and Game of Thrones dragons in our popular culture. With his biographical account of Gygax’s life, Witwer hopes to make the case for Gary’s expanding legacy. Witwer spoke to Inverse about how Gygax leveled-up his world — and ours.

Since you were five or six, you’ve been a D&D player — what spurred you on to look into the origins of Dungeons and Dragons?

I saw all of these pop culture phenomenas that found their origins in role-playing games. That is to say that they were originally unique to tabletop role-playing games and have since become mainstream-type stuff. To give you an example, there are elements to social media, that found their roots thematically in tabletop roleplaying games. It goes without saying things like massively multiplayer online role-playing games — MMOs — are derivative of role-playing games and tabletop role-playing games. Obviously computer role-playing games are derivative. Even first-person shooters. What I started to think about was, “Well, gosh. The guy that created these games really created an important following. He laid the foundation for all of these huge pop culture phenomena, this huge multi-billion dollar industry and, to a certain extent, he’s relatively unknown to the mainstream.”

I knew who he was — I grew up during the Satanic Panic, so I had some insight that there was this character out there named Gary Gygax, who was the subject of a witch hunt on one side and the other side he was kind of revered for being this tremendous pop culture icon. But there really wasn’t that much material out there about him and what he had done.

You write the book from Gary’s point of view, and include the way he’s thinking and his feelings. You have all of these interviews and his first-person writing, but you have to spackle through the gaps. (Gygax passed away in 2008, half a decade before Witwer began his book).

The conclusion I came to was, how do you tell the story of a story teller? And it didn’t feel right to tell the story in a traditional nonfiction, data-driven sort of way. It felt way more organic to tell the story, what’s happening, what’s going on with this guy, what’s he thinking, what’s he feeling, even if I had to push the envelope a little bit to get the spirit of every individual event. What happened? Why? How? It’s important to me for people to celebrate Gary and the events and the victories with him and also agonize the defeats. I don’t know if you really get that with traditional nonfiction style. So you take all these elements, and the cap on this whole thing for me was I love reading fantasy fiction. And the readers, they probably also love fantasy fiction like I do. Well, not just fantasy fiction because that’s the wrong way to put it, but fiction. It would be like reading fiction, you know, storytelling or roleplaying gamers, we like to cast spells or whatever. And so I really wanted a book that was nonfiction that read like fiction.

I was writing some chapters in a traditional non-fiction style, but I couldn’t get out of my head the scenes that were happening as I’m reading them. I’m reading letters, or I’m reading a Dragon magazine article, and I can’t get it out of my head when I’m reading these things. Not just what’s being said, but what’s happening. I was very inclined to see a lot of these things as scenes.

I went to unbelievable lengths to try to make sure this story was accurate, that is was properly qualified in places and areas where I was taking some artistic liberty.

It seems like Gary’s narrative arc, if you will, lends itself really well to this sort of psychological and emotional telling of the story. It’s rags to riches to, if not rags in the end, at least bittersweetness. It’s a sort of sad ending.

His personal life had all kinds of ups and downs. And you layer onto that the story of his game, which had all of this interesting intrigue. It was accused of being psychologically dangerous to teens. There were allegations that it was a recruitment tool for Satan worship. Then finally, you’ve got this company TSR, that he started, that prints the game. That story has all of the intrigue that the Apple-Steve Jobs story has or the story of Facebook. There were copyright conflicts, there were company lawsuits internally, there was staff fighting, and it ended in hostile takeover. I saw a multi-layered story here that tied together a lot of things.

Something about the whole thing, you know, the fact that he never necessarily got the riches he was due. But I think he was very much at peace with what he had done as well. He had really fallen into a kind of level of peace and redemption within himself and all the choices that he had made. But everything from when the company was sort of ripped out from right under him, until the very end you know, I think it’s a very up and down story and it certainly has a lot of sad elements. But I think it’s also often a story of victory.

Was there anything that jumped out when you were looking through Gary’s life?

Gary was a grinder. Gary was married before his 20th birthday. He was an everyman, to a certain extent, except he was blessed with an extraordinary intellect. After he gets married he has a bunch of kids. He gets into a regular job that he has the potential to excel at, but he’s struggling with the fact that he’s frankly obsessed with his hobbies and a lot of other things going on. So he’s grinding away, and by the time he invents D&D, he’s on the ropes, he’s almost on welfare, he’s a cobbler working for 50 cents a shoe, fixing shoes out of his basement. He’s trying to make ends meet and then all of a sudden, everything clicks and comes together and he comes up with an unbelievable game.

The next couple of things that I think really surprised me is that, you know, not only the simple binary things like not having a driver’s license, not going to high school, but the fact that this guy really pulled himself up by his bootstraps. That he was really on the ropes and this was kind of his one chance for greatness. And he absolutely nailed it.