How the Casual Cult of 'Back to the Future' Changed Movies

Robert Zemeckis created the culture of modern fandom then avoided all the pitfalls.

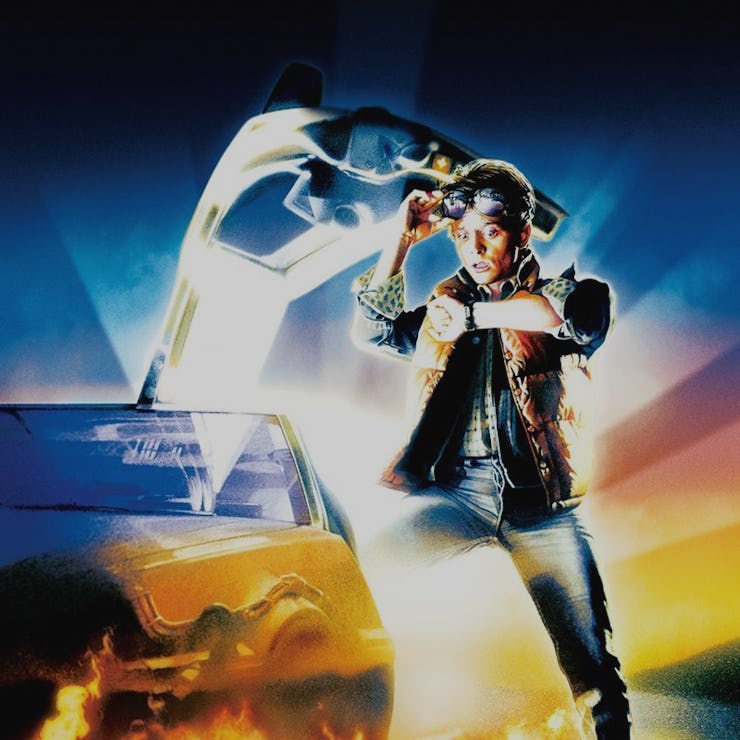

Robert Zemeckis’s time-traveling trilogy will constitute the first line of an obituary that might also mention Forrest Gump or that time he made a live action feature film with a cartoon rabbit years before computer animation. His masterwork will forever be a triptych, three movies he made about a crazy old scientist and a high school teenager getting stuck in 1955, 2015, and 1885. No wonder October 21, Back to the Future Day is going to see so many celebrations.

The reason for this isn’t Back to the Future so much as it is Back to the Future fans. It’s beyond unusual that such a something-for-everyone franchise inspired a loyal cult following. But it did, presumably because of those beautifully bifurcated plotlines, a bit of John Hughes interwoven with Steven Spielberg. The film is impressively mainstream and impressively ridiculous, which is a hell of an achievement whether or not Zemeckis intended to create the urtext of the basic nerd canon. And that is what the first movie became. By salting an accessible story with quotable lines and absurd pseudoscience then casting the ultimate everyman (Michael J. Fox) and the ultimate not everyman (Crispin Glover) as his rival/wingman/father, Zemeckis checked boxes no one even knew about at the time.

The first movie is so likable that it gets away with having incest as a subtext, a dubious accomplishment that has more to do with Christopher Lloyd’s arch performance contextualizing the narrative than the narrative itself, which is downright Freudian. Perhaps what’s most impressive about the film as a piece of pop culture is how finely tailored its weirdness is to its time. Like the DeLorean, an impractical car chosen over product placeable alternatives, Back to the Future is a product of a culture obsessed with the idea of looking forward and ill equipped to do so.

The “anything can happen” feel of the 80s — some of which must be blamed on a lack of basic engineering education — was doubly profound in Hollywood, which became a breeding ground for batshit, high-concept ideas. Imagine the pitch meeting on Back to the Future happening now.

Robert Zemeckis: Then, at the dance, he invents rock ‘n’ roll and there’s a time loop involving Chuck Barry.

Executive: Get the fuck out of my office.

It would be impossible to get the movie made as anything but an homage to the eighties (cough, Hot Tub Time Machine, cough). But back when Zemeckis was walking around with the script, there was an openness to both new ideas and silliness. Movies were broad and young audiences were fine with it. Risks were rewarded more regularly than they are today. Tickets sold.

The kids watching these movies had fewer entertainment options and felt more strongly about their choices, particularly when their choices didn’t involve Molly Ringwald. They wore out the VHS tapes and grew up pretending to escape from Biff and his goons on a hoverboard. These are the people who paved the way (lack of need for roads aside) to Comic Con, but Back to the Future still doesn’t attract the same constant fervor as something like Star Wars or even Lord of the Rings. The upcoming Back to the Future Day celebrations are one thing, but an anniversary is hardly the kind of pervasive intensity found in other equally as influential properties.

Instead, the BttF trilogy inhabits some sort of inter-geek purgatory where dude-bros and nerds alike can live in pop-cultural harmony, safe to reference their love of jigawatts and the Enchantment Under the Sea Dances without fear of backlash. People can quote it incessantly, and have adopted its vernacular by calling tough situations “heavy,” or mentioning that “when this baby hits 88 miles per hour, get ready to see some serious shit.” But it rarely goes beyond mere mutual recognition of its total and complete awesomeness.

You’d think a movie series as popular as Back to the Future would maybe earn enough clout to gets its own festival or ubiquitous merchandising empire. Where is its version of the Star Wars Celebration? Where is its Wizarding World of Harry Potter at Universal Studios? This month’s “We’re Going Back” 30th anniversary is one such event, but it’s still so relatively small it won’t break free from its niche. It did have its own ride at Universal Studios for 16 years, but that got shut down in 2007.

Questions about marketability and pervasiveness are not as nebulous as they seem. Zemeckis is the big bad guy in that regard, standing in the way of potential reboots or universe building. He intends to let the whole thing be and move on. Moving on has resulted in a lot of weird choices (see: Real Steel, Beowulf), but that’s no indictment. The kid, no longer a kid, stayed in the pictures. He’s a producer on The Walk, the Twin Towers tightrope picture currently in theaters. In a way, that film isn’t so different that BttF. It’s about a return to a certain sort of innocence and the love of the improbable. The French accents are just a bit grating.

The one thing about BttF that sets it apart from almost any other franchise is how often it’s screened. Nary a summer goes by when Back to the Future isn’t on a collapsable bit of cloth in a major city’s most major park. That’s because it isn’t good in the abstract, or interesting, or ironic, or requiring of any other qualifier. The movie is pure joy to watch.

The uniquely muted level of fanaticism around these films is beautiful because it’s a product of the movies themselves, not a hype machine or product tie-ins. Back to the Future reveled in the moral simplicity of the 50s and, in so doing, gave an audience access to a simple, joyful experience. Being a fan is an uncomplicated, borderline tautological experience because no one doesn’t like the movie. It’s the shared thing at the very edge of fandom’s culture of possession.