You'll Soon Be Able to Pay $1,000 to See Your Genetic Map

Veritas Genetics cracks long-sought affordable genome sequencing.

The head of a Massachusetts genetics company says anyone with $1,000 will be able to chart their genetic makeup “sooner than you’d think.”

“Ten years from now we’re going to look back and say ‘Why did we ever guess?’” Veritas Genetics CEO and co-founder Mirza Cifric tells Inverse. “You exercise and eat well and don’t smoke and think, ‘I’m doing all the right things’ but how can we know what the right things are for us, if we don’t fully understand who we are?”

Veritas Genetics planted its flag within the race for affordable sequencing Wednesday with an announcement it would offer full genome sequencing to Personal Genome Project (PGP) participants for under $1,000.

Since 2001, when the phrase was first used to described the impending era of personalized medicine, the “$1,0000 genome” has been the mantra of genetics researchers racing to stake their claim in a business that some estimate could be worth an annual $25 billion by 2021.

For now, the mapping is only available to the early adopters in the PGP (three of Veritas’ founders have work experience on that project) but Cifric says once the company has worked it out with federal regulations, a public offering is ready to go.

For just a hint of the possibilities this opens, scroll through the dozens of responses to Nature Genetic’s 2007 Question of the Year:

“What would you do if it became possible to sequence the equivalent of a full human genome for only $1,000?”

To start, we could:

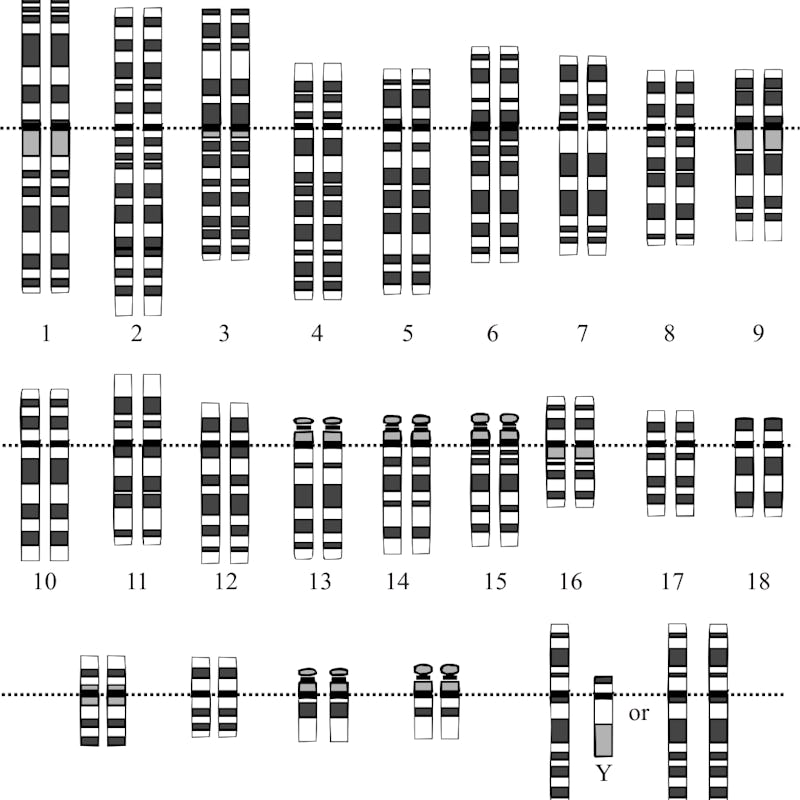

- Discover how many genetic variants inclining toward disease each of us carry (on average)

- Track the genetic lineage of entire villages and peoples

- Weed out abnormal and recessive genes

- And, maybe, get rich investing in data storage companies because, damn, are scientists going to need a whole lot of space to keep this information

It’s a big leap for a company that only launched its first product in June. Veritas’ myBRCA is a genetic screening test that identifies risks for ovarian and breast cancer. “The genome has been the Holy Grail for a while, but it turns out there’s many Holy Grails,” Cifric says.

Cifric advises potential patients to consider Bloomberg reporter John Lauerman, who in 2012 volunteered as a self-described genome crash-test dummy. His report uncovered an extremely rare JAK2 variant gene, often seen in people with cancer-like blood diseases as well as 90 percent of people suffering an oversupply of red blood cells called polycythemia vera. It can also be used to diagnose primary myelofibrosis, of which one in 10 cases will develop into leukemia. A 2010 Copenhagen genetic study found 14 out of 18 people with the variant developed some form of cancer, and at the time Lauerman was reporting his story all 18 patients with the variant were dead.

“In my opinion, that test absolutely saved his life,” Cifric says. “He went on to augment his lifestyle and his health choices, and that is one concrete example of how this is going to help people. The focus is around prevention, and living a longer and better life.

The Global Genes patient advocacy group estimates about 80 percent of rare diseases are genetic, and always present even if there are no apparent symptoms. About 350 million people worldwide are projected to be living with a rare condition.

The cost of sequencing itself has become affordable (it cost $2.7 billion to sequence the first human genome in 2003), so the challenge for Veritas is interpreting the data. Is your exercise and nutrition plan 8 percent of your overall health given your genetic base, or is it 80 percent? With your risk for lung cancer would you be better off moving to a city with cleaner air, or is that Thai place around the corner that irreplaceable?

There’s also the matter of privacy. Cifric calls the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act of 2008 a prescient law that already provides some protection from the culture that might spring from everyone’s most intimate histories being held on file, and while he declines to speculate on how future laws might interpret who has access to that information, says that as a private company Veritas would not release your results unless you requested them.

“If you chose for this to become part of your medical record that is entirely between you and your doctor,” he says. “This is not something that is done in a hospital, and it’s very different than how it would be done in a hospital. We do everything in our power to protect your information so that no one sees it without it being your choice.”

But if a few million Americans did get mapped, then decide they were fine with those results being made available to researchers, it would be an unprecedented pool of information.

“Academia and federal funding has done a phenomenal job here, but this business model could also be a real force for good,” he says. “A grant that lets you do 1,000 genomes is great, but what if you could get 10 or 25 million people? That’s what scientists are really after.

“That’s how we really move the needle not just in terms of prevention but saving lives.”