Making Adult Friends Is Easier Than We Think, Harder Than It Should Be

Americans spend a lot of time worrying about not having friends and even more time having them.

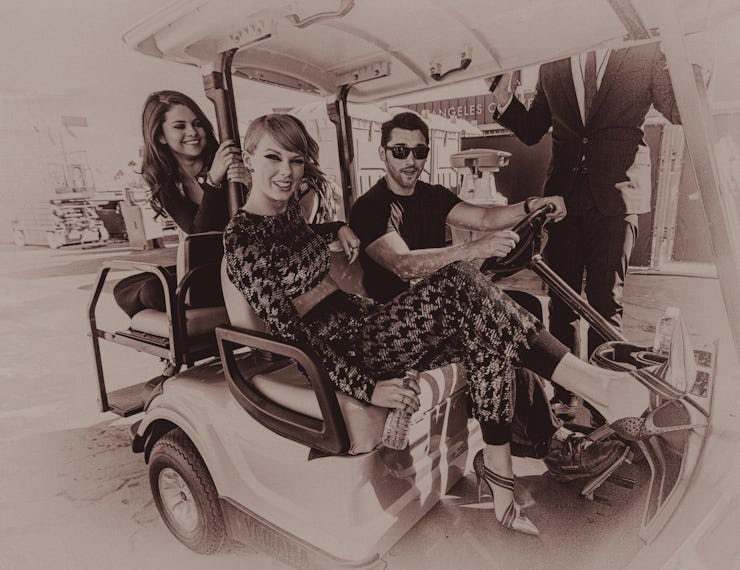

Drake, walking curse to treasured American athletes, once decreed, “And we in the club screaming / no new friends / no new friends / no new friends.” Meanwhile this summer, needing all the friends, Taylor Swift led the internet to set itself aflame with thoughts of squads. She didn’t start #squadgoals but the internet got distracted by slideshows, got really excited about think pieces about BFFs, and forgot. Clutching a copy of Bowling Alone, The New York Times harrumphed in the corner and said well actually you don’t have friends at work so don’t get too excited about the state of your relationships.

Depending on who has the microphone, adult friendship are either everywhere or nowhere. I’m an adult with friends but I can’t say too many of the newer ones began as complete strangers, like the friends I made at college. The process of turning acquaintances into actual we-go-hang-out friends is a weird one.

“If you look at our friends, everyone is from work or school,” says Arielle, who is 25, and yes, my friend. “Is this like, our peak of friend making? I mean, how many times have we gone to parties and realized we didn’t want to talk to anyone else.”

According to the majority of social science research, American adults don’t really need to worry that they’ll end up without pals. In a 2010 paper, University of Buffalo Assistant Professor Hua Wang writes, “Panic about the decline of social connectivity is an old story…. Despite these contentions, there has been continuing ethnographic and survey evidence of the abundance of supportive ties with friends and neighbors.” Pooling data from a survey of 2,000 households, Wang found that from 2002 to 2007, American adults between 25 and 74 had an abundance of friends. This whole debate of whether Americans are socially isolated should have been put to rest in 2012, argues Sonoma State University Professor Brian Gillespie, when the sociology pair Paik and Sanchagrin concluded that methodological flaws in prior research discounted the opposing argument.

However, Gillespie does point out that there is an increasing sense of the importance of friendship among American adults. Demographic trends like staying single longer, having smaller families, and living farther away from other family members all contribute to a growing emphasis on having a wide social circle. And besides the obvious pleasantness of not being lonely, this drive for friends is a good thing: People with more friends live longer, have better physical and mental health, and are generally more hopeful.

Then why does making adult friends feel so much harder than it used to? For one thing, studies have shown that our increase in social network size, after growing during adolescence and young adulthood, hits a plateau between our mid-‘20s and early ‘30s. Friends are lost and gained in almost equal measure during a tumultuous period of moving, getting new jobs, and having kids. Two camps are debating why our network fluctuates so much. Their theories essentially represent the opposing ways people think about change. On one side: the socioemotional selectivity theory, which argues that our social relationships change as we age because of our shifting perspective on how much time we have left to live. This theory is supported by Stanford psychology Professor Laura Carstensen, who says that at big life events, like turning 30, people try to get perspective on the here and now. “You tend to focus on what is most emotionally important to you,” Carstensen told The New York Times, “so you’re not interested in going to that cocktail party, you’re interested in spending time with your kids.”

On the other side: the social convoy theory, the idea that people have a network of social relationships of inner and outer circle friends that accompany them throughout their life. The level of closeness with certain people is affected by changes in one’s circumstance, and there is a natural assumption that outer circle friends are going to be less stable relationships. Which theory you personally feel is correct depends on whether you think altering circumstances or altering emotions is more likely to affect your relationships.

Stepping away from the theoretical, there are some nitty-gritty barriers that keep you from expanding your social circle. For example, researchers believe that it takes about five years to form a truly meaningful friendship. Close relationships that are formed quicker than that are usually because you’re both in a situation of insecurity. That’s why it took you years of company Christmas parties for you to realize Ryan from marketing was actually cool and one week of study abroad to put Kim in your mental list of future bridesmaids. Residential population doesn’t affect your number of friendships, so don’t think moving to a bigger city will automatically increase your crew. Adding to that, our potential network of meeting friends-of-friends basically maxes out at 250 people, and you’re likely to only really have up to a dozen people in your inner circle, a.k.a., “the sympathy group.”

You best be good to the friends you already have, ‘cause these people are basically your core group until you’re flirting away at a nursing home. The internet isn’t turning us into lonely hermits, but unlike say in elementary school, you’re not necessarily going to be friends with people just because you may see them everyday. If you are insistent on making new friends fine, ignore Drake and be a Taylor. Just please don’t call them your squad.

One thing you could do is just get drunk with who you want to be friends with. A 2015 Australian study found out what most people realize in college, which is that drinking, especially when “similar levels of intoxication are achieved,” builds intimacy. The study also found that recounting drinking stories and talking about them on social media strengthens friendship, but I can’t recommend the later because you also want to have a job. At the same time, the study warns that drinking can potentially damage new friendships, because nobody wants to take care of a drunk person you don’t feel particularly close with. As in all matters, watch your cups.

What you could do, and what you really should do, is up your capacity to be honest with a new person. New friendships among adults are based less on shared activities (like your adult kickball team) and more on self-disclosure. In the Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, authors of a 2010 paper argue that a moderate level of self-disclosure early on in a relationship increases the likelihood that people will become attached to each other. People who share more about themselves with their friends are likely to be more satisfied in their relationships, build new relationships, and receive more emotional support.

Geetika, who is 23, is one of the few new friends I’ve made in New York who doesn’t share the same alma mater. We joke that the building of our friendship felt a lot like dating — making dinner dates, talking about all the big stuff, generally making an effort.

“Outside of this setting [academia], when I meet new people today, it’s usually in a bar or at a party and there’s this rushed feeling where you have to decide right then and there whether or not you can be friends,” says Geetika. “But I think we became such good friends because we’re just two people who get along really well, and we were both really open to each other when we met. Basically, you can’t be friends with everyone. But you should be open with everyone.”

There’s a methodology to everything, including making friends. If people aren’t receptive to your friendship, forget them. Literally. Your brain can only remember about 150 people meaningfully, so you might as well make them the best you can.