What the Politics of "20,000 Leagues Under The Sea" Mean

Bringing a Jules Verne Classic to the big screen means diving into real issues.

American audiences hold numerous misconceptions about the proto-science fiction and surrealist writer Jules Verne. In his native France, Verne is hailed as an artist of great depth and peculiarity. In America, he is basically considered a font of source material for movies. To be sure, Disney cartoons have furthered his legacy, but they’ve also denuded much of his work of its original significance.

Though history may look askance on some of Verne’s opinions (he didn’t, for instance, believe in evolution), it’s worth noting he did have opinions — lots of them. Verne’s stories are about squids and dinosaurs and trips around the world, but they are also about technology and the way humans interact with it and harness it for good and evil. Verne wasn’t unique among writers in taking the Industrial Revolution seriously, but he took it way more seriously than most.

English-speaking readers can be forgiven for not appreciating the depth of Verne’s metaphors because the truly awful translations that have proliferated stateside strip out anything resembling subtlety. This makes reading Verne a bit of a misadventure, but it also makes the work more attractive to a broader audience. And you better believe Hollywood noticed.

Verne’s 20,000 Leagues Under The Sea is already a famous movie that aged poorly and it soon will be again. Bryan Singer, director of the X-Men reboots, announced last week that he’s written and will direct a remake of the classic. Interestingly, the novel was supposed to be remade by Director David Fincher, but, according to rumors, Disney sunk the project over Fincher’s desire to keep the nationality of the main character French. Fincher, it seems, got a little too close to the original material.

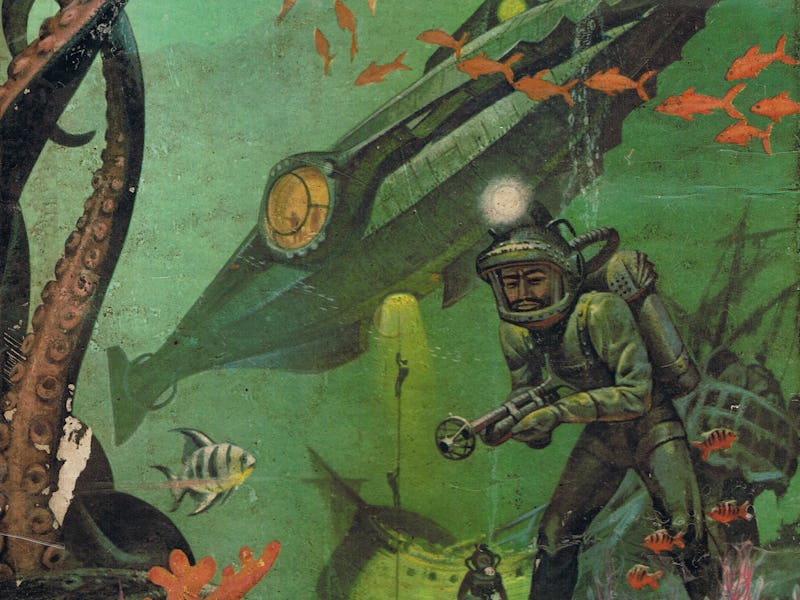

And the original novel was intended to be controversial. Captain Nemo, the sort-of protagonist of the story, is a Robin Hood of the seas, a brilliant, moody, vengeance-minded researcher who, due to murky circumstances, has been cast out of civilization. Nemo’s high-powered submarine, the Nautilus, has to remain secret from discovery lest its cutting-edge innovations be stolen. He fears the nascent military industrial complex, is deeply suspicious of colonial states (he’s Indian so that’s pretty understandable), and believes that innovation is the domain of a sort of self-nominated elite. Basically, he’s a libertarian in the Peter Thiel mode.

Interestingly, Verne first conceived of Nemo as a former Polish military man, a scarred rebel avenging the Russian Czar’s murder of his family. It was Verne’s editor, the publisher, Pierre-Jules Hetzel, who changed Nemo to an Indian scofflaw, a subject rebelling against the reach of the crown. Verne’s reluctance to incorporate this changeover was captured in a fascinating correspondence with Hetzel that played out as 20,000 Leagues was being serialized.

“I see now that you are imagining a fellow very different from my own,” Verne wrote of Hetzel’s change to Nemo. “You have said to me that abolition of slavery is the greatest economic fact of our time. I agree, but it is totally irrelevant here. We must keep vague [Nemo]’s nationality, his person, and the events that threw him into this strange existence…. If Nemo wanted to avenge himself on the slavers, he would only need to serve in Grant’s army.”

Hetzel held final editorial control so Nemo stayed out of the Civil War.

“In social matters my taste is order,” Verne remarked during a late-in-life run for political office. “[M]y hope is to create within the present government a reasonable party that balances respect for justice and religious belief with consideration for people, the arts, and life itself.”

In the end, it’s a difficult task exploring the murky leagues of Verne, Hetzel, and the creative collaboration that went into the adventurous masterpiece — exactly the sort of murky task that would excite David Fincher. But don’t expect Bryan Singer’s Nemo to get too political. He’s going to have a CGI squid to fight and politics stops, as they say, at the water’s edge.

Will we see an edgier version of Verne than we’re used to as Americans? Probably. But we won’t see the French version and we’ll never see a Polish Nemo.