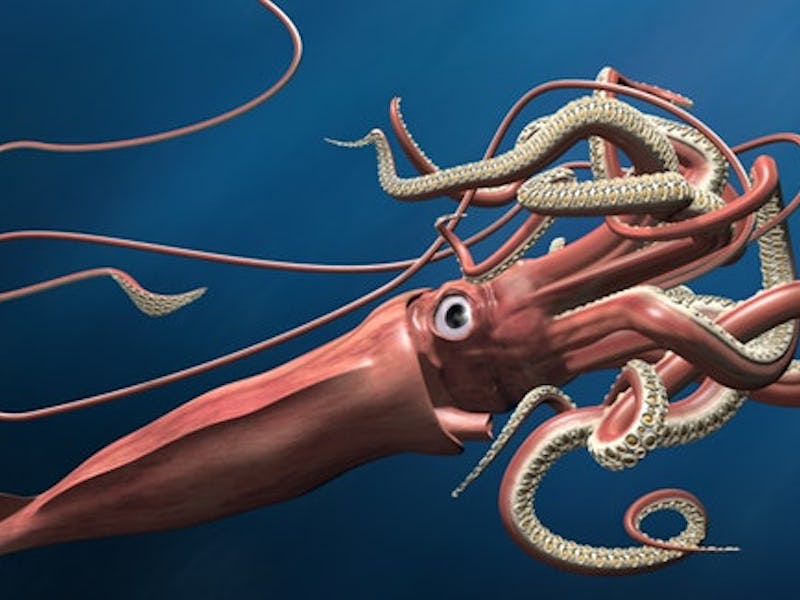

Inverse Daily: giant squid, decoded

There's more to these ocean-dwelling giants than legend would suggest.

Whenever I walk through New York City, I’m struck by the vast amount of sculpted concrete, from its bridges to its looming buildings. Sometimes I feel like I’m walking through the dark, dense city of the movie Blade Runner, where I look forward to meeting a beautiful, human-like robot (“replicant”) that will cause me to question the nature of my own existence.

Yet the concrete-filled, dense city envisioned in Blade Runner may actually be on its way out, especially if the world wants to meet its climate goals. Inverse’s Sarah Wells has the story on how scientists have come up with a new, more climate-friendly substance known as “living concrete.” This concrete of the future can perform some biological functions, like reforming when split in half.

This article is an adapted version of the Inverse Daily newsletter. Subscribe for free and earn rewards for reading every day.

Wow, the future is alive! Be sure to check out our other stories on the sheer strangeness of life on planet Earth, from legendary, giant squids to prehistoric scorpions.

INVERSE QUOTE OF THE DAY

“A genome is a first step for answering a lot of questions about the biology of these very weird animals [squids]”

— Caroline Albertin, the Hibbitt Fellow at the University of Chicago.

- Read More: “Gene study reveals giant squid may be intelligent.”

Concrete is alive!

Concrete is all around us — as roads, bridges, and, arguably, ugly Brutalist architecture. And while it may seem innocuous, the production of this material is generating more than double the CO2 emissions of the whole aviation industry. To escape the concrete prison we’ve made for ourselves, a team of researchers thought outside the box to build greener, easily reproducible living concrete.

The concrete is made using a scaffold of sand and hydrogel and a bacteria called Synechococcus. The bacteria draws nutrients from the hydrogel in order to grow and mineralize — kind of like a seashell. The researchers found that this approach maintained the same strength as concrete, but in a much greener way. They also found that reproducing the material was much easier. Just like a worm that self-heals when cut in half, the team found that a single sample could be divided into up to eight pieces.

Researchers say this makes it an attractive candidate for extraterrestrial construction. (Looking at you, Mars.) But, while a promising proof-of-concept, this material is far from ready for commercial rollout. One particular hurdle the researchers have yet to overcome is the material’s sensitivity to temperature and humidity. The material only performed its best when at a comfortable 50 percent humidity and 68 degrees Fahrenheit. But honestly, can you blame it?

Read more:

The legendary, giant squid, decoded

The giant squid is a scientific mystery that’s puzzled humans for centuries — since it was first observed in the mid-1800s. Swimming deep in the ocean, the elusive creature has been historically tough to study. We’ve never caught one and kept it alive, for instance. So there’s much about them that we have yet to discover.

A new research development is a step toward those discoveries. Researchers were able to sequence a giant squid’s genome, determining that it has about 2.7 billion DNA base pairs in its genome. For context, we humans have about 3 billion. Based on the squid’s genes, scientists also learned that the animals might be incredibly intelligent.

With the new findings, the researchers say they’ve set the stage to answer long-standing questions about the monstrous sea-dweller — like how it came to be so huge and how it survives at the ocean’s depths.

Related stories:

This paddleboarding giant squid may have died from sex injuries

America, the sedentary

Who’s the fittest of them all? Americans are some of the sickest and heaviest people on the planet. And in a new series of country-wide maps, the United States’ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) paint a bleak picture of one lifestyle factor driving these negative health outcomes: physical inactivity.

The maps show over 15 percent of adults in every single state report leading a sedentary lifestyle, which means a lifestyle that involves little to no physical activity whatsoever. Instead of walking the dog or going on a hike, it seems like a lot of Americans are sitting at home on the couch, in their cars, or at their desks.

Overall, people living out West were the most physically active, while Southerners were the most sedentary. Colorado scored the lowest, where 17.3 percent of people in the state report being physically inactive. But over in Mississippi, the least physically active state, one in three adults lead sedentary lifestyles.

Word to the wise: Getting active doesn’t require a gym membership or proximity to the mountains — people can add exercise “snacks,” or quick hits of movement to their day, like taking the stairs or walking to the grocery store.

The data are not suggesting that Southerners are lazy and Westerners are fit. There is a complicated array of cultural, socioeconomic, and environmental factors that make regular movement and physical activity easier for some people compared to others.

But ultimately, the researchers say Americans aren’t moving enough, and staying still has enormous costs to our health and longevity.

Related stories:

- CDC maps

- A surprisingly short period of inactivity can damage your health, scientists learn

- 9 common myths about exercise, debunked

Old, old scorpions

Apart from their quick reflexes and venomous sting, scorpions have something big to offer: Their long line of ancestors stretches back to the earliest years of animal life on Earth. So new research uncovering the oldest scorpion on record is particularly exciting for scientists studying how animals left the sea in order to thrive on land.

“Prior to this, all of animal life is in the ocean,” lead author Andrew Wendruff tells Inverse.

The newly found fossil is from the early Silurian period, dating back approximately 437.5 to 436.5 million years. The new species, Parioscorpio venator, came from Waukesha Biota in Wisconsin. It unseats the previous oldest-ever scorpion fossil, Dolichophonus loudonensis, found in Scotland.

Scorpions’ place in both prehistoric and modern times are part of the reason studying them is so fascinating, Wendruff says: “Scorpions are interesting because they are among the earliest terrestrial arthropod groups found in the fossil record that are still around today.”

Related stories:

- Terrifying dinosaur-age fossils resemble fanged spiders with tails

- Scientists have invented a scorpion-milking robot

Do you have a sugar addiction?

Have you ever bought a big stash of candy and then noticed — by way of a mysterious chain of events — it disappeared. How did you eat it all so fast? And why?

It turns out that candy — and sugar, more specifically — can be addictive. “Sugar alters brain circuitry in ways that are similar to, for example, cocaine, which is well-known to alter the dopamine and opioid systems in the brain,” said Anna Landau, an author of a new study on sugar’s addictive potential. But is it chemically addictive or psychologically addictive?

Well, the scientific jury is still out on that one.

Related stories:

Meanwhile …

- A new theory explains how life arose after the dinosaurs went extinct.

- Elon Musk revealed construction of Starship is rapidly moving forward with a new photo.

- PS5 leaks reveal Sony may debut next-gen console in “less than four weeks.”

- Rise of Skywalker theory explains why Anakin’s Force ghost never showed up.

- Why we need Captain Picard more than ever in 2020.

Inverse Loot

Subscribe to Inverse Loot and learn about these deals first.