Candida auris: This "urgent threat" could be the next big superbug

The deadly fungus first appeared in an ear.

Nearly a decade ago, a strange and life-threatening fungus emerged in the far-flung corners of the globe. In 2009, it appeared in the ear of a patient in Japan. By 2013 and 2014, it was in Venezuela, India, South Africa, and Kuwait. By 2016 the fungus had moved to New York and now, in 2020, it’s solidified its place as a “serious global health threat,” according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The fungus, called Candida auris, is a type of yeast that can linger on the skin, and cause nondescript symptoms like fever and chills. It usually affects patients who are already sick and the elderly — it appears to thrive in places like retirement homes and hospitals. When it gets into the bloodstream, it’s incredibly dangerous: the CDC estimates that one in three patients with an invasive C. auris infection die. It’s important to note that many patients are already suffering from other conditions, so it’s hard to tell the role that C. auris plays in their demise.

Regardless, in 2019, the CDC put C. auris on its list of urgent threats. That “urgent threat” status is the CDC’s category of highest concern and places the fungus in the company of infections like super gonorrhea.

Scientists are particularly concerned because C. auris can develop the ability to resist three major classes of antibiotics and it showed this dangerous capability in three separate patients described in a CDC report released Thursday.

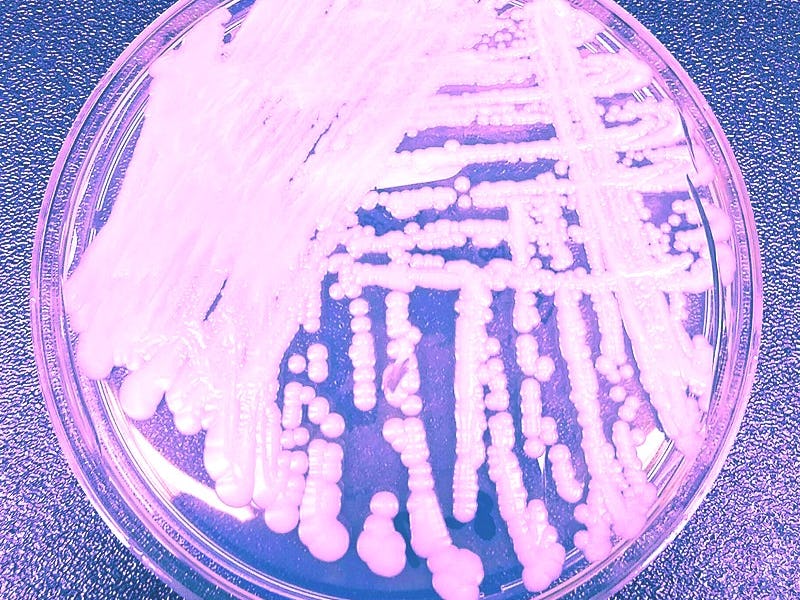

C. Auris, an emerging superbug that the CDC has classified as an "urgent" threat.

Tom Chiller is the chief of the CDC’s Mycotic Diseases Branch. He tells Inverse that this report contains “concerning” information showing that C. auris can develop resistance to a class of antibiotics called echinocandins. These target the fungal cell wall.

That’s concerning because echinocandins are the first thing doctors reach for to treat the disease since it is often already resistant to other antibiotics.

“What’s particularly concerning in the New York report. and what we’ve seen elsewhere, is that strains can develop resistance to echinocandins as well, making them ‘pan-resistant,’” Chiller says.

Here’s what we know so far about this emerging superbug.

C. auris and antibiotic resistance

There have been reports of C. auris cases in 40 countries. In the United States, it has turned up in 13 states. Illinois, New York, and New Jersey have all had over 100 cases. In the US the vast majority of cases have occurred in New York: According to the CDC report, there were 801 cases this June.

The recent CDC report provides information on two groups of C. auris patients in New York who were analyzed on two separate occasions — indicative of just how resistant C. auris can be to antibiotics.

C. auris cases in the US as of October 2019.

In the first batch of 277 patients, 99.6 percent were resistant to fluconazole (which is a member of one class of anti-fungal drugs). Furthermore, 61.3 percent were resistant to a second class of antibiotics. Fortunately, in this case, none of the fungi was resistant to the to a third wave of antibiotics — echinocandins.

However, that luck didn’t quite last: In the second group (331 patients). 3.9 percent of patients had developed resistance to those echinocandins as well.

In this group, three patients had C. auris infections that were resistant to all three classes of those drugs — which, in Chiller’s words, makes them “pan-resistant.” Those patients were all over 50-years-old and lived in New York City.

Two of those patients died of infections that may have been related to C. auris, though the CDC is unsure of how the fungus played a role in their deaths. The third patient died of underlying medical conditions.

Importantly, these patients had no connections to one another, which means that the fungus developed the ability to resist all three kinds of antibiotics three separate times. Those “pan resistant” C. auris isolates are still rare, the CDC report cautions, but adds that their “emergence is concerning.”

Where did C. auris come from?

A paper published in The Journal of Fungi in July 2019 found that C. auris’ genetic makeup suggests that it has “been on Earth for many years.” But oddly, scientists have not been able to find any traces of C. auris in nature or in animals.

The closest thing we have to a trace of a sample of C. auris that didn’t emerge from humans was found in a swimming pool in the Netherlands, though that was just one isolated report.

However, regardless of how long C. auris has been around, the enduring mystery is: why it has only shown up in humans within the past decade? It’s especially strange because it has seemingly spontaneously emerged on three continents at the same time, in patients with no connections to one another.

A timeline of C. Auris spread in the 2010s. Into the 2020s, scientist are still concerned about the rise of this antibiotic resistant superbug.

There are a few explanations (none are conclusive). The authors of the July 2019 paper suggest that increased access to medical care may have brought people carrying C. auris into close contact. Others studies suggest that global climate change has made C. auris more “thermally tolerant.” That means that it’s better at thriving in hot environments, like the human body.

How can we stop C. auris?

What we do know is that C. auris thrives in hospitals. Chiller’s previous presentations note that it can survive many different cleaning materials and tends to linger on surfaces in patient rooms, like tables, chairs, railings or beds.

"Early detection and infection control in hospitals and nursing homes is the most important way to stop its spread."

Places in hospital rooms where C. Auris tends to persist, according to Chiller's July 2019 report.

“Early detection and infection control in hospitals and nursing homes is the most important way to stop its spread,” says Chiller.

As for treatment, this report from New York alone doesn’t provide enough information to provide insight on how to deal with it. For now, the first line of defense is still echinocandin medications. But, given its threat level, scientists may need to come up with a plan B — just in case.