Gnarly lungs found in a museum basement rewrite the history of measles

Measles and cities may go hand in hand.

Measles made an unexpected return from the brink of elimination in 2019 when the disease spread through unvaccinated groups around the world. Even though we have a vaccine for measles, it’s still an old disease that still spreads quickly and devastatingly.

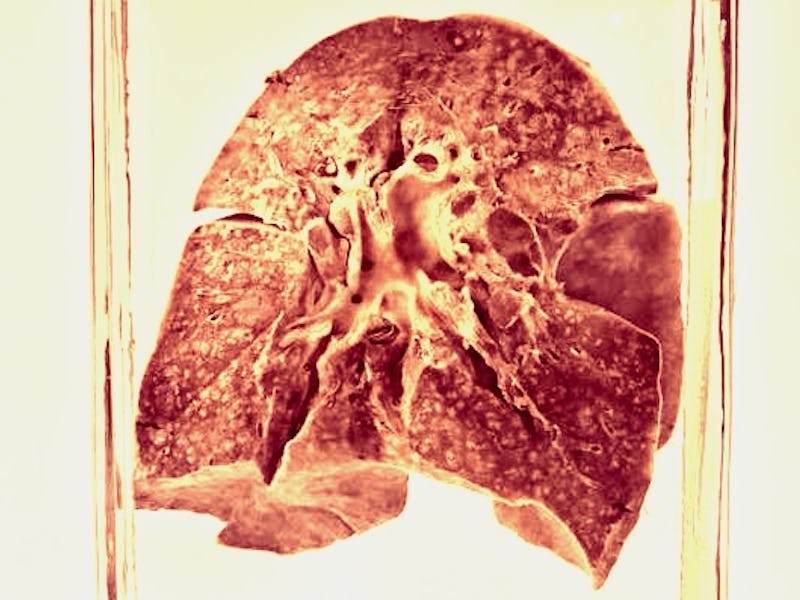

And some newly discovered gnarly lungs from a basement in Berlin show us when this whole problem began.

Analysis of lungs from a two-year-old girl who died in 1912 have pushed back the origin of measles by 1,500 years. “We sequenced the genome of a 1912 measles virus and used selection-aware molecular clock modeling to determine the divergence date of measles virus and rinderpest virus,” write scientists in their research paper.

What they found was that these 1912 lungs suggest that the human measles virus arose in the 4th century BCE, which roughly corresponds with the height of classical Greece.

Historical accounts from 10th century Persian physicians, or from battles in eighth century France hinted that the measles may have arisen around 1,000 CE — though that was just a rough estimate.

In the paper published on the pre-print website BioRxiv the authors argue the 4th century BCE may be the “earliest possible date for the establishment of measles in human populations.”

Preserved lungs from 1912 have pushed back the emergence of measles by 1,500 years.

The lungs were originally collected during an autopsy after their original owner died of measles-related bronchopneumonia on June 3, 1912, according to the paper’s supplementary material. Then, they remained untouched for over a century.

As Science magazine reported, these lungs were found by the study’s senior author Sébastien Calvignac-Spencer in a basement at the Berlin Museum of Medical History. That museum is already known for a collection of organs suspended in jars, reminiscent of Snape’s potion classroom.

When scientists analyzed the lungs, they found that they contained traces of a measles virus, which they compared to another sample of the measles virus from the 1960s, and other records of measles genome. Ultimately, they found that the previous estimates couldn’t account for the number of genetic differences between the virus found in those lungs, and other genetically distinct measles viruses in the family tree.

These lungs on their own can’t confirm that measles arose in the fourth century, but they do suggest that the 4th century is a “lower bound” of possible dates. Their interpretation of these findings also rewrites measles’ history, and links it to the emergence of cities large enough to enable the measles to thrive.

The red zone is the rough period of time when these scientists believes that measles became infectious to humans. The dotted line represents a threshold of 250,000 people, which the measles virus needs to sustain itself. The author argue that measles emerged just as humans started gathering in large enough groups to allow continuous transmission.

Measles is a “fast-evolving virus,” the authors write. They argue that it first arose in large populations of cows or other ungulates (animals with hooves) in about the 3rd century BCE. During that time, one genetically lucky virus may have evolved the ability to jump ship from animals to humans.

That alone though, wouldn’t be enough for measles to become the powerful, infectious disease we know today. To become a persistent threat, these scientists suggest that measles needs a critical community size of about 250,000 to 500,000 people. If the population is that large, the disease can sustain itself indefinitely.

If humans had been living in small, isolated groups, those hosts would be “dead ends.” Measles confers immunity once you get it once. Before the safe and effective measles vaccine, the disease could wipe out a small population, leave survivors immune, and leave the virus with nowhere else to go.

If measles arose during this time period, the team believes that it happened to coincide with a time in history when century caused humans to reach that critical population threshold, which allowed the virus to thrive.

“Indeed, antiquity witnessed an important upsurge in population sizes in Eurasia and South and East Asia,” they write.

It’s hard to know for sure if these cities were large enough to sustain measles transmission, or if the disease really did manage to catch hold in some of our earliest urban environments. But if it did, these ancient cities could have tipped the balance, and helped create the virus that would go on to define define centuries of infectious disease.

Abstract:

Many infectious diseases are thought to have emerged in humans after the Neolithic revolution. While it is broadly accepted that this also applies to measles, the exact date of emergence for this disease is controversial. Here, we sequenced the genome of a 1912 measles virus and used selection-aware molecular clock modeling to determine the divergence date of measles virus and rinderpest virus. This divergence date represents the earliest possible date for the establishment of measles in human populations. Our analyses show that the measles virus potentially arose as early as the 4th century BCE, rekindling the recently challenged hypothesis of an antique origin of this disease.