What would make you trust a robot?

A new study says that if robots explain what they're doing, they can foster that trickiest of emotions in humans: trust.

People don’t trust self-driving cars. They trust themselves to drive. Yes, a robot doesn’t fall asleep or get drunk or look at their phone. But people don’t care. They don’t trust self-driving cars. How much? Well, AAA’s annual automated vehicle survey from March 2019 found that 71 percent of people are “afraid” to ride in fully self-driving vehicles. Scientists are trying to get people to trust A.I robots more. How? By having them explain themselves.

“In the past, robotics wasn’t closely tied to psychology. This is changing,” says Dr. Hongjing Lu, a professor in the department of psychology and statistics at UCLA, speaking to Inverse during a press conference about her team’s recent study offering a potentially new way forward for A.I. “Trust is a central component of humans and robots working together.”

You interact with artificial intelligence everyday. There’s a strong chance that it’s part of the reason you’re reading this right now, and from here data points will be gathered and some algorithm will take this story into account as it decides what ads to present on social media. Apps like Google Maps and Uber use it all the time to find the best routes for cars.

These examples feel passive—anyone who has used social media or Google Maps can attest to their ease and quickness. Users can assume that some work is going on behind-the-scenes but can’t look underneath the hood. It’s enough to make their algorithms feel invisible, like the editing of a good movie. But just as editors never get their due, the UCLA team feels that the hidden nature of algorithms has made people suspicious of them in larger, more active scenarios.

But, of course, what is trust?

“Trust is a very complex psychological construct,” Lu says. “It can emerge in different ways at different stages of the relationship development. So therefore, we started from the very first set of trusted development. When they say I trust you to do X as we do the past acts, they basically have the believe that do the past acts with competence and we can predict that you will actually do the task right in the way, so conveying under the impression of competence and the predictability is important for fostering human trust and human robotics business.

So to agitate on such impression the machine not only and need to achieve past performance, but it also needs to provide good explanation for it’s behavior. That’s one of the core ideas in this paper.”

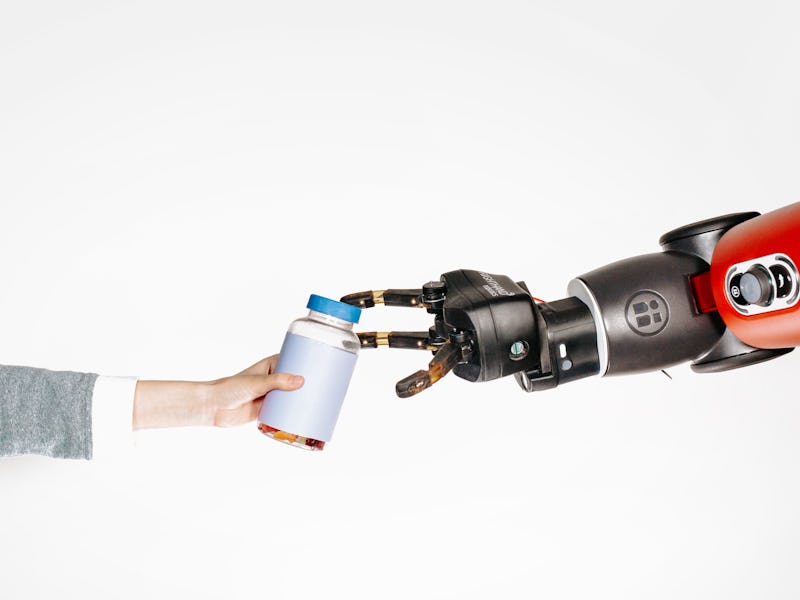

Scientists decided that opening a pill bottle would provide enough of a challenge for their robot to be a worthy test. It’s a complex task, as any human with a headache can attest. There’s the act of it requires “pushing on a lid or somehow subtly manipulating the lid using force, and the robot learns to mechanisms to complete the task,” says Mark Edmonds, a PhD Candidate in Computer Science at UCLA who also participated in the teleconference.

The robot learned these actions from human demonstrations. Not purely visual either—the human who first opened the pill bottle were wearing haptic gloves that allowed but their motions and their applied pressure to be recorded. The gloves were able to capture the subtlety of human action, and the robot arm followed. The AI was then able to produce a series of explanations for each of its actions.

One hundred and fifty students participated in the study’s next part. They observed the robot’s different explanations for its actions, either in visualizations or in text summaries. “Ideally, these explanations convey why the robot is executing the current action and can foster trust from humans,” says Edmonds.

“After we asked humans to give a rating for how much they trusted the robot after observing different explanations,” he continues.

The explanations were able to foster trust, but not all explanations were equal. “Both the haptic and the symbolic explanations fostered those trust in the highest production accuracy,” Edmonds says, referring to physical explanations or visualizations. The worst at fostering trust? The written word.

Edmonds and the other scientists were caught off guard by the lack of trust given to a written summary. “This is all a bit surprising because the summary description actually provides an explanation for the critical portion of the task and so one might think that this would be enough to foster trust, but it looks like for a sequence of tasks it’s not, and additionally the robot formed best when using both be haptic information to make decisions,” he says.

The finding could play a huge role in fostering trust with future AI. Edmonds tells Inverse that lifting the curtain on A.I could be crucial in the coming years, as the technology takes an increasingly proactive role in people’s lives.

“I think part of the purpose of providing these explanations may not be the always provide them or like you can always record them like doctors you would think, but maybe another purposeful of this would be to establish trust. So, I mean most machine learning and robotics right now is largely black box. So, you really don’t understand what’s happening in the middle. All you understand is what is the input and what is the output, and if the system is performing well on the output, then you don’t really worry about what’s going on in between.

I guess with more important domains and applications like autonomous driving or something like that, understanding why or how the machine makes a decision is important for someone to get in the car in the first place. So, would people be willing to get in a car where you don’t really understand how to make decisions. So, providing these explanations at least initially or having them be available can help people actually trust the machine, trust the machine is going to behave reasonably and not do something dangerous.”