Life in the cosmos may depend on these 4 key ingredients

Alien hunters take note: Whether exoplanets host life comes down to a few essential criteria.

In 1992, astronomers Aleksander Wolszczan and Dale Frail were observing a pulsar star located some 2,300 lightyears away when they noticed something strange. The usually regular rhythm of its pulsating light seemed to be skipping a beat.

The reason behind its off-beat pulse led to a discovery that would change the course of astronomical exploration: The star had two planets orbiting around it.

These were the first planets ever observed outside of our Solar System. And so, the study of exoplanets — and the search for those that may support life like that found on Earth — was born.

So what essential ingredients do you need for life? Inverse spoke to the experts to find out what they think are the key factors for habitability elsewhere in the universe.

How many exoplanets are there?

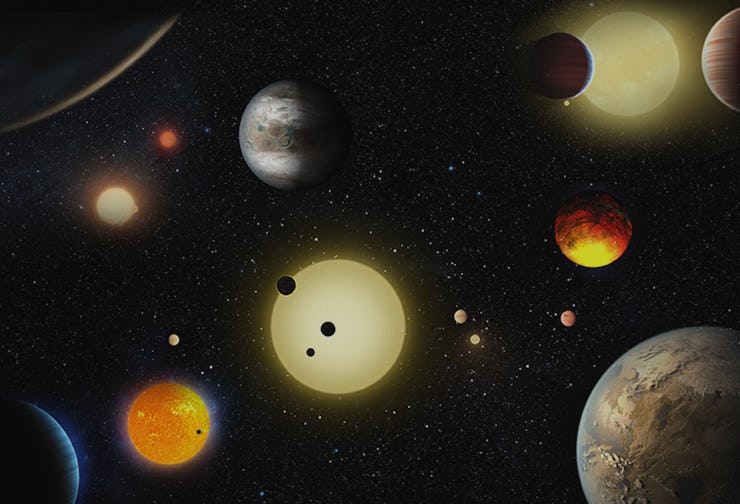

Currently, we know of about 4,000 exoplanets orbiting around all types of stars — and 3,000 more suspected exoplanets are awaiting confirmation.

The explosion in exoplanets is thanks to NASA’s Kepler mission and the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) missions. Kepler zooms in on stars to see if there are planets orbiting within their habitable zone, while TESS surveys 200,000 of the brightest stars in the sky.

The hope driving these efforts is that we might find worlds similar to our own — in other words, capable of supporting life. Doing so might finally answer the question of whether or not we are alone in the cosmos.

Are we alone in the universe?

But what, exactly, habitable means — or, more profoundly, what life might look like — for these far-away planets is one of the hottest debates in astronomy.

Part of the problem stems from our current isolation. We only have one example to base our expectations for other planets off, says Billy Quarles, a researcher at the Georgia Institute of Technology’s School of Physics.

“There’s been lots of debate over what we should expect,” Quarles tells Inverse. “But the easiest thing is to look for what we know.”

Exoplanets need an atmosphere

The first thing that scientists try to detect on an exoplanet is whether there is an atmosphere and, if yes, what it’s made of. “The main thing that you need is to get better information about what the atmosphere is made of,” Emily Lakdawalla, a planetary geologist at The Planetary Society, tells Inverse.

A planet’s atmosphere needs to be thick enough to transfer heat and offer insulation. If the Earth didn’t have its atmosphere, for example, the temperature at the surface would reach as low as -20 degrees Celsius, Quarles says.

Earth’s atmosphere is what makes it habitable compared to its neighboring planet Venus. Although the two planets have many similarities, Venus can’t sustain life because its atmosphere — which is mostly carbon dioxide, nitrogen, and sulfuric acid — makes it the hottest planet in the Solar System.

Venus has been described as an Earth-like planet, but with a hellish atmosphere

But it’s hard to get a handle on the atmosphere for exoplanets that are located very far away, Lakdawalla says. “There aren’t very many planets from which we get enough signal.” Improving upon the tools we have now would be a “good first step” for furthering the search for life in the cosmos, she says.

Exoplanets need water

When a planet is in its host star’s habitable zone, that means it is a comfortable-enough distance away from the star’s heat and close enough from the extreme cold of space for liquid water to exist at the surface. This delicate balance of neither too hot nor too cold gives this special region its other monicker: The ‘Goldilocks zone.’

On Earth, water acts as a solvent, meaning that it dissolves other substances, enabling it to transport chemicals, minerals, and other molecules that are the building blocks of biology.

Earth is currently the only celestial body proven to have liquid water flow through it.

However, Lakdawalla points out that while water may be the best solvent, it is not the only one. Scientists have long suspected that life may exist on Titan, Saturn’s largest moon, even though its bodies of liquid are filled with methane and ethane rather than water, but could still support some form of methane-based biological existence.

Exoplanets need an energy source

A lot of attention is paid to exoplanets that fall within that Goldilocks zone. But if it happens to be outside of the host star’s habitable zone, all is not lost. It could still sustain life if it has a different source of energy. Energy can come from a planet’s host star, but it could also come from chemical or geothermal sources.

This is true for Europa, one of Jupiter’s 79 moons. Europa is outside of the Sun’s habitable zone, but the radiation created by Jupiter’s intense magnetic field is provides enough energy to the moon that some believe it could sustain life on its icy body.

Although Europa is outside of the Sun's habitable zone, it has a source of energy to sustain life

Europa (and Venus) goes against the very idea of a ‘habitable zone.’ “Some people are against that term, because they want to go to Europa and say that there’s life there,” Quarles says.

Exoplanets need the right star

Our Solar System owes whatever habitability is has in part to the Sun’s disposition. Our host star is a relatively calm, predictable star. That’s not always the case for other planetary systems, which may be orbiting around a volatile, highly chaotic star.

Stable stars that don’t switch up their brightness or radiation in an unpredictable manner, nor send out violent solar flares capable of eradicating life on its orbiting planets, are an essential ingredient in making life on other worlds possible.

“That may be one of the hardest criteria to satisfy,” Lakdawalla says. “You need the environment to be stable over time. Our star is a stable star, but most other stars aren’t.”

Will we find life in space?

The search for exoplanets with habitable environments could one day lead to the holy grail of astronomy: Answering for once and for all whether or not we are alone in the vast cosmos.

“The idea is if you look at places that are ‘Earth-like,’ you might find life and you might not,” Lakdawalla says. “That’ll answer whether we’re common in the universe or we aren’t.”

But there is a fundamental difference between searching for habitability and finding intelligent life that resembles our own species, or the myriad advanced societies of Star Wars. Life may exist in different forms — some familiar, some totally, well, alien. Mars, for example, is theorized to house microbial life beneath the planet’s dusty surface — scientists think it may also have hosted life on its surface at some point. Meanwhile, on Titan, a moon orbiting Saturn, scientists think there’s a chance life would be based on hydrocarbons, like methane — that would look very different to life as we know it.

A view of Titan, where some scientists think methane-based life could have arisen.

If we do find life out in the cosmos, we would run into a more mundane problem. Back-and-forth messages would take hundreds of thousands of years to go between Earth and the planet, because most exoplanets are just so far from our own.

If humans wished to pack up and migrate to a habitable planet, they’d run into the same problem: The trip would simply take too long.

“We would need some new physics,” Quarles says. “We would have to discover something completely new in order to close that gap.”

Of course, there are other — more human — reasons to study the strangely familiar planetary bodies in the distant universe.

“There’s a lot of us who are studying exoplanets just because they’re cool,” Lakdawalla says. “We only have eight planets in our Solar System, and we’re finding a wide variety of completely different planets out there.”

Variety, after all, is the spice of life.