Self-driving robotic glider can hear nuclear explosions underwater

There's a whole world of sound down there.

The mysteries of the ocean deep may not be such a mystery after all.

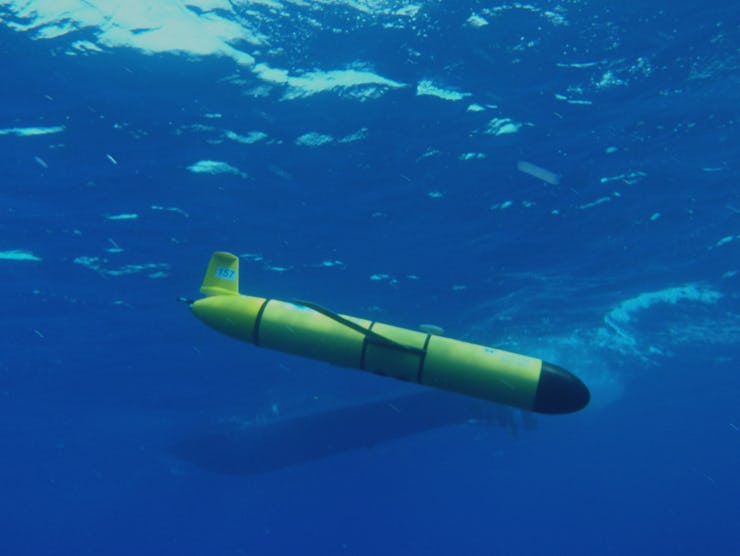

A team of researchers at Oregon State University and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration have created a robotic glider that can measure sounds from the ocean. Unlike previous systems which used underwater microphones attached to ships, the gliders are cheaper, quieter, and capable of covering a lot of ground. The research was published Wednesday in the journal PLOS ONE.

Although listening to the sound of the deep blue sea may seem like a niche hobby, sticking a microphone into the ocean could reveal a treasure trove of data. It can be used to spot huge events like tsunamis, earthquakes, or even nuclear explosions. It could also help protect marine life.

“Healthy marine ecosystems need to have noise levels within particular ranges,” said Joe Haxel, an assistant professor in the College of Earth, Ocean, and Atmospheric Sciences at Oregon State and part of NOAA’s Pacific Marine Environmental Lab Acoustics program. “As an analogy for humans it’s the difference between living in the country or living in the city or somewhere really loud.”

As the world looks to better protect the natural environment, it could come at an ideal time.

Diving with the glider.

The glider: how it works

All current systems that measure ocean noise have limitations.

One method is to attach a hydrophone, or an underwater microphone, to a fixed mooring. This is popular but means the microphone doesn’t move around. Another option is to use a research ship, but this costs a lot of money and can also disturb the marine life it’s meant to be measuring.

The autonomous glider could offer an answer without compromise. It measures five foot long and weighs 120 pounds. These contraptions usually carry a multitude of sensors for surveying the ocean, and see regular use among researchers.

The team sent the craft on an 18-day voyage, moving between Gray’s Harbor in Washington and Brookings in Oregon. That’s a distance of around 285 miles. The glider worked along the continental shelf break, around 30 miles away from the shore and the point where the sea depth starts to drop a lot more. This is a migration path for animals, making it an ideal area of research.

Gray's Harbor and Brookings.

After the glider collected the data, the team then used an algorithm to remove the noise made by the glider in its operations. The team then used that recording and compared it with the recordings from moorings during the same time. The results were impressive, showing the system could offer greatly improved data from hydrophones, moving through the water to collect sounds with ease.

The glider is not the first robot that could help locate nuclear activity. A team from Princeton University explained earlier this month how its “inspector bot,” equipped with neutron counters, could be used to autonomously survey test areas and check for nuclear warheads.

As companies like Rolls-Royce also look at automating shipping routes, it seems the ocean of the future could be increasingly automated and provide more data than ever.