Space travel may change the human heart

The results shed light on what life in space might do to the human body -- and what happens after returning to Earth.

Spending time in the microgravity environment aboard the International Space Station appears to alter gene expression in the human heart. The results shed light on what life in space might do to the human body — and what happens when that body returns to Earth.

Humans have been venturing out into space for over 50 years now, but very little is known about the toll microgravity might take on the human body. With the age of commercial space travel fast approaching, it is increasingly critical to understand how our bodies adapt to space flight.

“Space is our next frontier. In the next 100 years, humans will be traveling through space all the time,” says Joseph Wu, Stanford University professor and senior author on the study.

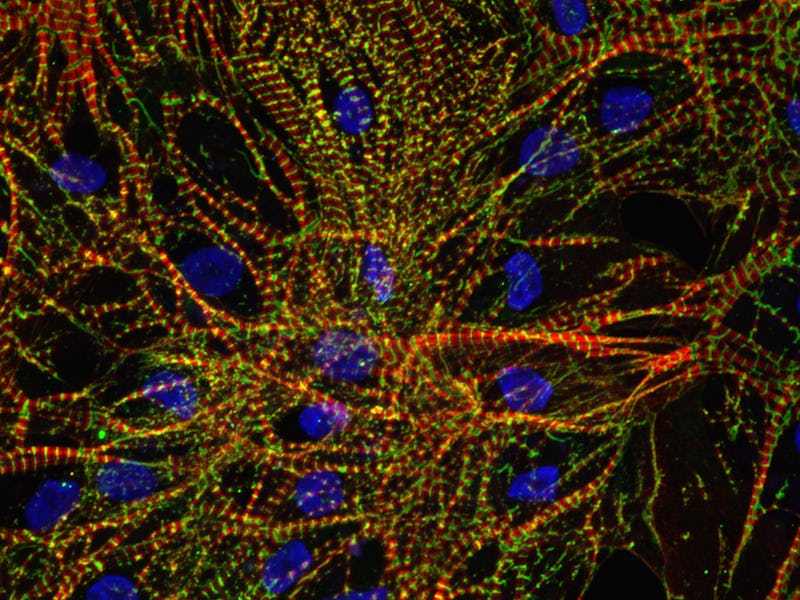

To understand the effect of space travel on our most crucial, blood-pumping organ, in 2016 Wu’s team sent beating, human-induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes, a kind of heart muscle cell, to the International Space Station.

Astronauts examined the cell culture plates onboard the ISS

The results, published in the journal Stem Cell Reports, show that time in a microgravity environment alters gene expression in the heart muscle cells, but most of these changes revert after the cells are back on Earth.

This is the first study to look at the effects of microgravity on a cellular level, the researchers say.

Modeling the heart in space

To create the stem-cell model, the researchers harvested blood cells from three people, none of whom had a history of heart disease. They then reprogrammed the cells to become cardiomyocytes. The cells were sent to the ISS and cultured aboard, staying in the microgravity environment for a total of five and a half weeks before being flown home.

By comparing the cells’ gene expression in-space, on return and to controls, the researchers found that time in space altered the expression patterns in 2,635 of the cells’ genes. Most of the altered genes are related to mitochondrial metabolism, the process by which nutrients are converted into energy and used to carry out different functions in cells. Expression patterns looked similar to controls after 10 days back on Earth — a possible sign that the body can reverse adaptations to life in space.

“We do know that heart muscle cells can adapt. It’s hard to tell if these changes are necessarily negative or if they are natural adaptations,” says Alexa Wnorowski, a graduate student at Stanford University who was involved in the study.

“It’s hard for us to come up with a conclusion of what that means. It gives us a future direction to look into,” she says.

The team plans to use the data and compare it with both records of physiological changes in astronauts during missions and with symptoms of heart disease in order to get a better sense of these adaptations’ long-term effects.

The study could also have implications on heart health for those that don’t even plan to travel beyond the stars, say the researchers, offering insight into how the environment may affect gene expression in heart cells here on Earth.

“That’s one of the hopes for the directions that this type of research might go,” Wnorowski tells Inverse. “If we figure out that microgravity is able to replicate some of the gene expressions we see in diseases on Earth.”