An ancient asteroid may have had a delightful effect on Earth's sea life

Asteroid dust smothered Earth, leading to a cooling effect.

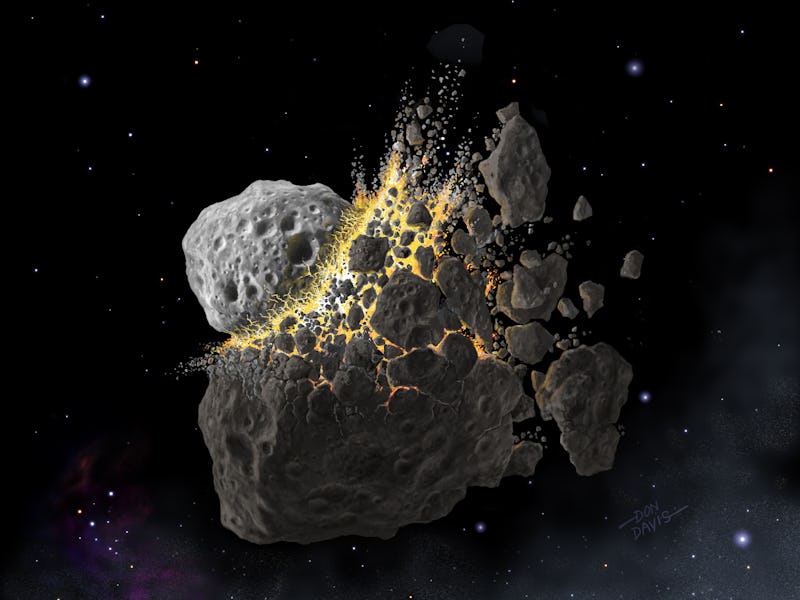

About 466 million years ago, a massive, 93-mile-wide asteroid disintegrated somewhere between Jupiter and Mars, sending waves of dust that shrouded the Earth. New research in the journal Science Advances suggests that this asteroid collision in outer space may have triggered an ice age down here on Earth, leading to a huge increase in the number and diversity of living things in the ancient oceans.

The study, published on Wednesday, presents evidence that the fragmented asteroid’s dust filled the inner solar system to the point that it shaded the Earth from the sun’s radiation. As the planet got cooler, ice began to build up at higher altitudes near the northern and southern poles, causing sea levels to fall.

By tracking down traces of space dust in two formations of sedimentary rock, one in Sweden and one in Russia, the scientists behind the new study made the connection between this major cosmic event and the concurrent cooling event down here on Earth by matching the timelines of the two events together.

Marine organisms like trilobites proliferated during the ice age that came after the asteroid's dust cloaked Earth.

Birger Schmitz, Ph.D., a geology professor at Lund University in Sweden and the first author of the new study, tells Inverse that he had been trying to prove this hypothesis for decades.

“I had a gut feeling for 25 years that there was this relation between the fossil meteorites and this very strange sea level fall,” Schmitz says. “It just clicked, it took a couple of seconds and then it was absolutely clear.”

Space dust falls onto Earth all the time, but the rock formations Schmitz and his colleagues investigated showed evidence of an exceptionally large amount of space dust. He compares it to taking the dust bag out of your vacuum cleaner and flinging it open in the middle of your living room, essentially covering the entire room in dust.

“This is what happened, at a much larger scale,” he says.

The team of scientists tracked down the space dust in ancient rocks that once covered sea floors on Earth. In order to strip the rock down to its cosmic insides, the scientists treated samples with acid that disintegrated the stones, leaving behind the bits that came down from space.

Researchers identified a clear line in sedimentary rock formations where matter from a broken-up asteroid had fallen to Earth.

Prior to the space vacuum bag explosion, the Earth was a largely warm world where different regions were all more or less around the same temperatures. And warm worlds tend to be more homogenous than those with varying temperatures, where different species survive in different climatic circumstances.

The ice age that the team suspects was triggered by the asteroid dust may have eventually led to an increased biodiversity on Earth by creating different climate zones. This explosion in biodiversity, too, is evidenced in the fossil record.

“This is the first time that it has been shown that dust can cool the Earth, this is perhaps relevant when it comes to mitigation of global warming,” Schmitz says.

This section of sediment, in Kinnekulle, Sweden, shows evidence of asteroid dust that coincided with the beginning of an ice age on Earth.

In 2012, researchers from Scotland suggested triggering the partial destruction of an asteroid to deploy space dust around our planet in order to shield Earth from solar radiation and combat global warming effects. And Schmitz believes that it is a realistic solution, since his recent findings suggest that it has happened before.

By continuing to look at geological events from an astronomical perspective, Schmitz hopes to inspire the growth of a field of research that combines the two disciplines.

Another trilobite that evolved during this particular ice age.

“We want to connect the history of space with the history of life and Earth and this is what we have done with this study,” Schmitz says.

“A lot of things happen in space around us…and it’s a little bit weird that Earth scientists, geologists have never thought in these lines.”

Abstract: The breakup of the L-chondrite parent body in the asteroid belt 466 million years (Ma) ago still delivers almost a third of all meteorites falling on Earth. Our new extraterrestrial chromite and 3He data for Ordovician sediments show that the breakup took place just at the onset of a major, eustatic sea level fall previously attributed to an Ordovician ice age. Shortly after the breakup, the flux to Earth of the most fine-grained, extraterrestrial material increased by three to four orders of magnitude. In the present stratosphere, extraterrestrial dust represents 1% of all the dust and has no climatic significance. Extraordinary amounts of dust in the entire inner solar system during >2 Ma following the L-chondrite breakup cooled Earth and triggered Ordovician icehouse conditions, sea level fall, and major faunal turnovers related to the Great Ordovician Biodiversification Event.