Scientists Discover Stress Comes From an Unlikely Source in the Body

“Bone was invented in part to escape danger.”

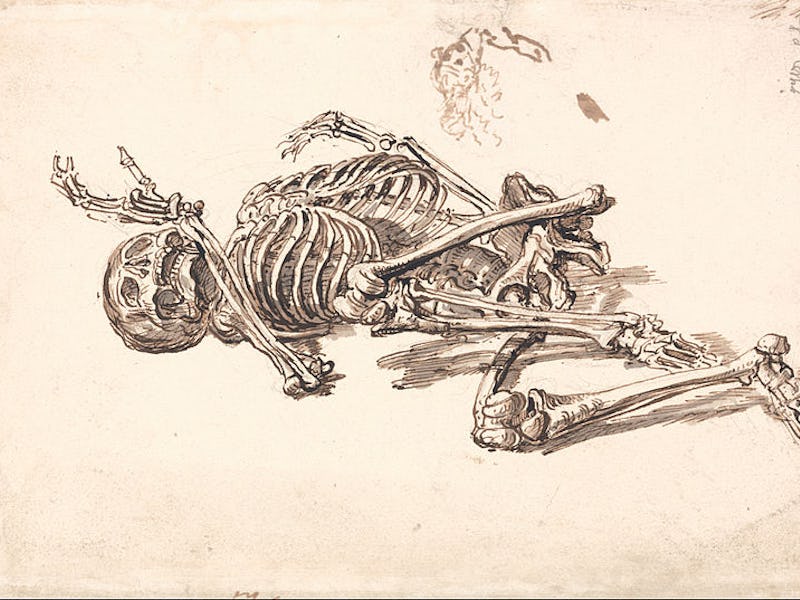

Bones are more than just the scaffolding for our body lumps. Bones are rigid organs filled with a honeycomb-like matrix, and while they do protect our internal organs, they also secret several hormones — including one that’s closely tied to our ability to handle stress.

That hormone is called osteocalcin, and it’s been linked to crucial human physiological processes like brain development, the ability to exercise, and male fertility. In a study released Thursday in Cell Metabolism, scientists took our understanding of osteocalcin one essential step forward with the big reveal that bones release osteocalcin in response to acute stress.

Senior author Gerard Karsenty, MD, Ph.D., tells Inverse that this finding verifies an earlier hypothesis: “Bone was invented in part to escape danger.”

Is stress stored in the bones?

The traditional understanding of how the body reacts to stress, commonly known as the “fight-or-flight” response, is that when a person perceives danger their brain’s amygdala sends a distress signal to the hypothalamus. Once the hypothalamus receives that signal, it activates the sympathetic nervous system by sending signals through the autonomic nerves to the adrenal glands. Then, the adrenal glands pump epinephrine, otherwise known as adrenaline, into the bloodstream.

This triggers a number of physiological changes meant to help you deal with whatever you’ve perceived as scary — whether someone is chasing after you or you have a public speaking engagement. But interestingly, previous work established that patients and animals who lack cortisol and additional molecules produced by adrenal glands still have the same physiological response to acute stress.

So how’s that possible?

Bones, in part, evolved to help vertebrates escape from danger in the wild.

This study says the answer could be bones. Karsenty and his colleagues have long suspected that bone-derived hormones may contribute to the acute stress response because bones are so good at helping us respond to danger in general. After all, bone, through osteocalcin, contributes to energy metabolism, reproduction, memory, and the ability to exercise. Since all of these functions help animals survive hostile environments, the team surmised that “bone evolved to enable vertebrates to overcome acute danger.”

So they tested the idea with mice, and in turn discovered that when they restrained the mice for 45 minutes, the level of osteocalcin in their blood rose by 50 percent. Then they upped the sense of danger by exposing the mice to stressors like a mild electrical shock to the foot or the scent of fox urine. Fifteen minutes after exposure to these stimuli, the mice’s level of osteocalcin rose by 150 percent.

When they asked human volunteers to speak in public or undergo cross-examination they found a similar response: The stressors corresponded to a significant rise in the participants’ circulating levels of osteocalcin. At the same time, the levels of the other bone hormones stayed the same, stress or not.

To double-check whether osteocalcin was definitely triggering the fight-or-flight mode, the team also genetically engineered mice to not make osteocalcin. When these osteocalcin-less mice went through the same stress, nothing happened — the hormone didn’t rise, and the mice did not appear afraid. But when regular mice were then injected with osteocalcin and were not exposed to a stressor, they still displayed fight-or-flight symptoms.

Analysis of the brains of these mice revealed that osteocalcin is released into the bloodstream by osteoblasts — cells that are responsible for bone formation — and this release subdues activity in the parasympathetic nervous system. That’s the system that tells the body that it’s okay to chill and feel calm. When this system is subdued, the body goes into full-stress mode, and adrenaline is released.

That connection to adrenaline is why the team suspects a “bone-derived signal is necessary to develop an acute stress response” — and demonstrates that the osteocalcin could be more useful to animals in the face of danger than the adrenal glands. If anything, it’s good to know that our bodies have got our back — especially the bits that explain why we have a back in the first place.

Abstract:

We hypothesized that bone evolved, in part, to enhance the ability of bony vertebrates to escape danger in the wild. In support of this notion, we show here that a bone-derived signal is necessary to develop an acute stress response (ASR). Indeed, exposure to various types of stressors in mice, rats (rodents), and humans leads to a rapid and selective surge of circulating bioactive osteocalcin because stressors favor the uptake by osteoblasts of glutamate, which prevents inactivation of osteocalcin prior to its secretion. Osteocalcin permits manifestations of the ASR to unfold by signaling in post-synaptic parasympathetic neurons to inhibit their activity, thereby leaving the sympathetic tone unopposed. Like wild-type animals, adrenalectomized rodents and adrenal-insufficient patients can develop an ASR, and genetic studies suggest that this is due to their high circulating osteocalcin levels. We propose that osteocalcin defines a bony-vertebrate-specific endocrine mediation of the ASR.