Humans Can Reverse Their Biological Age, Shows a 'Curious Case' Study

In a yearlong clinical trial, three drugs rolled back participants' epigenetic clock.

Someone call Brad Pitt, because it might be time for a sci-fi spin on The Curious Case of Benjamin Button. New research shows humans may be able to reverse their epigenetic clocks, a measure of biological age, with a trio of drugs that are already on the market.

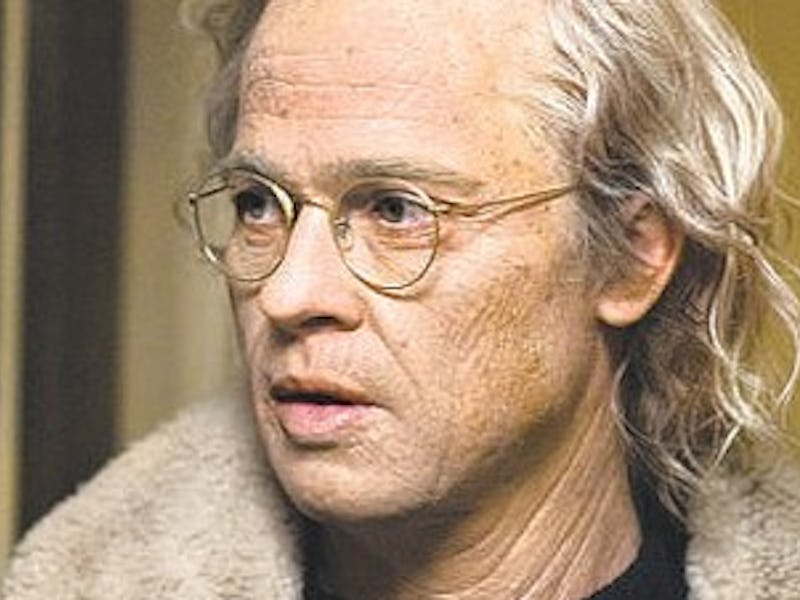

In a small, 1-year clinical trial published Thursday in the journal Aging Cell, nine participants took three common medications — growth hormone and two diabetes drugs — and reversed their biological age by 2-and-a-half years on average. Greg Fahy, Ph.D., lead author of the study and chief science officer of anti-aging therapeutics company Intervene Immune, tells Inverse that this research proves the concept that biological aging may not be unstoppable.

“One of the lessons that we can draw from the study is that aging is not necessarily something that is beyond our control,” he says. “In fact it seems that aging is largely controlled by biological processes that we may be able to influence.”

As opposed to chronological age, the number of years a person has lived, biological age is how old a person seems. It’s measured by looking at epigenetic markers that indicate chemical changes to DNA over time — like “decorations on your DNA,” Fahy says.

One such marker is the addition of methyl groups to DNA, a process called methylation. Previous research led by University of California, Los Angeles professor Steve Horvath, Ph.D., who conducted an analysis of this clinical trial, has shown a relationship between aging and methylation. Horvath found the process to be a key metric in developing epigenetic clocks.

Epigenetic markers indicate a person's biological age, which is different from their chronological age.

Those clocks can be “a beautiful tool for people who want to study changing aging,” Fahy says. In the past, conducting a trial to determine how a therapy affects lifespan would require following the person until, well, the end of their life. Using epigenetic clocks to determine biological age means getting those answers much sooner.

“If this really all works, and we can show it’s really as safe as we believe it is, this is something that can be used to treat aging very soon,” Fahy says.

That’s in part because Fahy’s trial used three common drugs that are already FDA-approved: recombinant human growth hormone (rhGH) and two diabetes medications, dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) and metformin.

The goal of the trial was to regenerate the thymus, the “master gland of the immune system,” Fahy says. The gland takes white blood cells from bone marrow and converts them into T-cells, which fight off diseases including bacteria, viruses, and even cancer. “It’s an essential process for staying alive,” Fahy says.

But humans begin to lose that function around the time they hit puberty.

“The thymus starts to wither and die around the age of 12 or 13,” Fahy says.

Growth hormone has been shown to reconstitute the thymus in animal studies, but it can also raise insulin levels. So Fahy and his team gave participants metformin to keep those levels in check.

Fahy and his team say biological age and chronological age don't have to remain the same.

The third drug, DHEA, was included because of a theory of Fahy’s. Young people have higher growth hormone levels without the increased insulin — and Fahy believes that’s due to their higher levels of DHEA.

To test out his hunch, Fahy used a peculiar subject: himself. He took human growth hormone for a week, and his insulin levels increased by 50%. Then he added DHEA, and “the increase was 100% reversed,” he says.

"Before I try anything on anyone else, I like to do it on myself first."

After the yearlong trial, Horvath’s analysis of the participants’ epigenetic clocks shocked Fahy. He expected to see changes in the thymus, but not necessarily an overall clock rollback.

“We really didn’t know it was going to have a broader benefit of reducing aging in a more generalized way,” Fahy says. (He admits there had been hints, however, including obscure research conducted in Italy that indicated thymus transplants in older animals would rejuvenate the liver, brain, insulin response, and thyroid hormone status.)

Fahy’s study didn’t have a control group, and it included only nine people, all white men. The next steps, he says, are to conduct more research that include more groups of people. But first, Fahy plans to do a bit more self-experimentation.

“Before I try anything on anyone else, I like to do it on myself first,” Fahy says, to “make sure it’s safe and make sure it works in the way I think it will.”

Fahy says his team has a lot more to learn, but he’s encouraged by the preliminary results. “It’s so exciting that we’re able to ask the question now,” he says, “even if we can’t answer it.”