As the 1990’s edged towards mid-life, the Mighty Morphin’ Power Rangers were a ubiquitous franchise that reached frenzied levels the post-Reagan economy could only dream of. Parents fought for toys at Christmas. Ratings went through the roof. A live appearance with the cast shut down Florida.

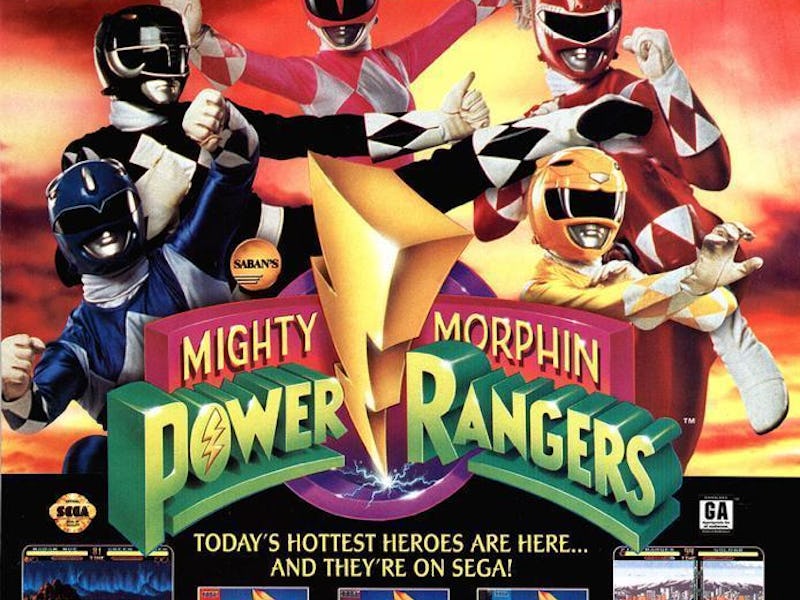

Video games, then dominated by Sega and Nintendo, were a natural extension of that marketing machine. In 1994, Power Rangers invaded gaming with a blitzkrieg, with a game on every console fathomable at the time. But each game was different, and on the Sega Genesis the Power Rangers went Street Fighter.

Even in the mid-‘90s, gaming standards were high. Doom II, Final Fantasy VI, the revolutionary Donkey Kong Country, the hotly-anticipated Sonic the Hedgehog 3 — there was no way could a cash-in Power Rangers game could compete. Especially in the fighting game genre, where Mortal Kombat changed everything and Killer Instinct and Tekken reigned supreme. What the hell would Power Rangers do? Predictably, not a lot.

A super-abridged version of the show’s first season, Mighty Morphin’ Power Rangers was a single-player kumite where you select one of the five Power Rangers to duke it out with a monster sent by Rita Repulsa, an evil alien queen and master of the occult. It’s best of two in each fight, because that’s how superheroes always beat the villains, with Olympic-style rules. Defeating the monster grows them in size, starting the colossal kaiju beatdown with the Megazord just like every Power Rangers episode. And just like those episodes, playing it is just as unpleasant to watch.

Whether as a Ranger or a Megazord, the combat mechanics are as shallow as this audience’s side of the swimming pool. There’s no strategy like you’d find in Street Fighter II. None of the Rangers have any “better” moves than the other, and all the villains fight nearly exactly the same. Every strategy to beat them is “get the hell out of the way.”

Stringing combos are a chore. There’s a noticeable time delay, a fraction of a fraction of a second, that prevents alternating punches and kicks in succession. When you actually do, the roundhouse kick sends them flying to the other side of the screen, stopping any euphoric sense of accomplishment or skill.

But that’s the hook: It was a basic, stripped-down fighting game for a preschool audience. Kids of this age can be intimidated by ultra-complicated fighting games — I certainly was. That’s how I gravitated towards this game, besides the Power Rangers being slapped on it, and set the groundwork for when I’d eventually get to Dead or Alive and Tekken.

The multiplayer is the only chance of any kind of enjoyment for players past age six. (Or adults with access to alcohol.) Every character is unlocked from the get-go, including the Green Ranger and the hella sweet Dragonzord (but no Dragonzord Fighting Mode, LAME) and this see-saws the value: you can save time and get to playing, but there’s no reward for time and effort so what the hell is the point in any of this.

Perhaps there wasn’t. Like the show, the purpose feels empty and hollow as its kingdom of toys. It’s just to play. For a six-year-old, that’s all they just want.

Today, even for some adults, purely playing is the only purpose.