These Feces-Carrying Navigators Use Earthly Cues to Avoid Poop Battles

For a dung beetle, poop is life.

Let’s get it out of the way: Dung beetles eat poop. They need to eat the poop — all animals need nitrogen to build protein, and dung beetles get their nitrogen from the feces of warm-blooded herbivores. They also need the poop because it becomes a nursery for their beetle babies. Accordingly, poop is a very hot commodity that dung beetles battle over.

But battling also means you’re at risk of losing your poop, so dung beetles have evolved some unique skills to keep their spoils. On Monday, scientists announced in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences that they’ve discovered a particular dung beetle ability that allows them to transport precious poop away from competitors. A series of indoor and outdoor experiments demonstrated that dung beetles sometimes use the wind as their guide, especially when celestial cues are not available.

We can rewind there: Like the navigators of yore, some dung beetles use the skies above to transport feces. While 90 percent of beetles transport poop by tunneling underground, the others either dwell in the manure full-time, or they pack the dung into round balls and roll it away.

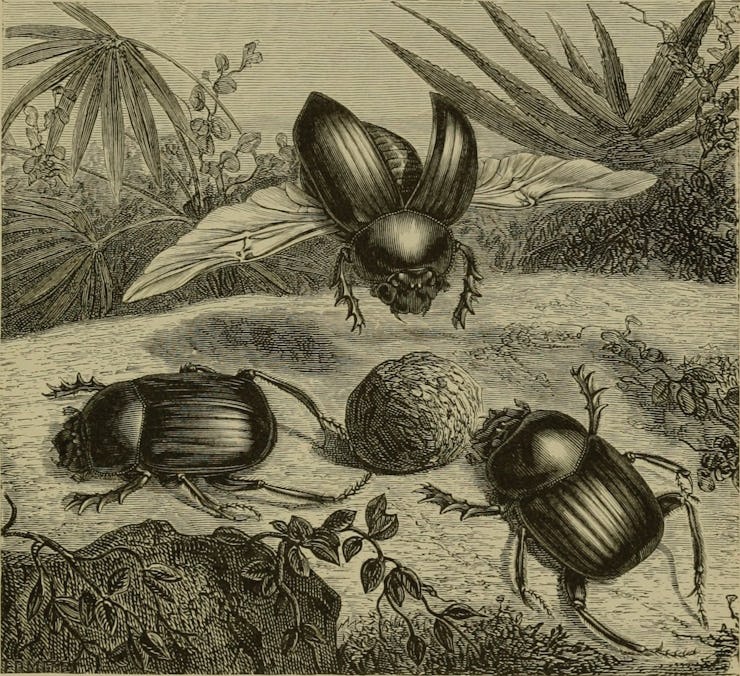

Two dung beetles fight over a ball of poop.

These beetles, the rollers, have been documented moving in straight lines away from dung. The lines are possible because they have special photoreceptors in their eyes that allow them to detect patterns of polarized light that appear around the sun. In turn, the beetles use the light to orient themselves and transport the ball of poop away to a safer spot.

The question asked by this study was How do these rollers still manage to move in straight lines when sunlight isn’t there? Previously, scientists found that one species of dung beetle, Scarabaeus satyrus, uses the Milky Way as its guide on moonless nights. However, the dung beetle Scarabaeus lamarcki is only active during the day — ruling out the star-guide option.

So the scientists took S. lamaracki and evaluated how it moved with its dung-balls, both outdoors and in lab settings. They observed that when the sun is at its highest elevation during the day, the beetles had the hardest time using the light to move in a straight line. However, when this happened, they started to rely on another element that the scientists hypothesized would help: wind. The wind has previously been shown to help insects like ants and cockroaches accurately move toward their nests.

A roller begins its roll.

In the beetle’s natural environment, the scientists noted that when the sun reaches its highest elevation, wind speeds tend to peak. In the indoor setting, the scientists saw that when sunlight was taken away, wind cues also improved the precision of the beetle’s orientation. To understand what mechanism could be driving the ability to use the wind as a guide, the scientists amputated some of the beetles’ antennae. When the experiment was repeated, these beetles could no longer orient themselves correctly.

Because dung beetles are capable of transferring sensory cues between the sun and wind compasses, the researchers hypothesize that these navigational abilities are united by a common neural network for spatial memory.

“The directional information can be transferred between these 2 sensory modalities, suggesting that they are combined in the spatial memory network in the beetle’s brain,” the paper’s authors write. “This flexible use of compass cue preferences relative to the prevailing visual and mechanosensory scenery provides a simple, yet effective, mechanism for enabling precise compass orientation at any time of the day.”

And with a keen spatial network, beetles are able to get dung away from piles as quickly as possible — a resource so important, scientists compare it to finding a bag of money on the street.

Abstract:

South African ball-rolling dung beetles exhibit a unique orientation behavior to avoid competition for food: after forming a piece of dung into a ball, they efficiently escape with it from the dung pile along a straight-line path. To keep track of their heading, these animals use celestial cues, such as the sun, as an orientation reference. Here we show that wind can also be used as a guiding cue for the ball-rolling beetles. We demonstrate that this mechanosensory compass cue is only used when skylight cues are difficult to read, i.e., when the sun is close to the zenith. This raises the question of how the beetles combine multimodal orientation input to obtain a robust heading estimate. To study this, we performed behavioral experiments in a tightly controlled indoor arena. This revealed that the beetles register directional information provided by the sun and the wind and can use them in a weighted manner. Moreover, the directional information can be transferred between these 2 sensory modalities, suggesting that they are combined in the spatial memory network in the beetle’s brain. This flexible use of compass cue preferences relative to the prevailing visual and mechanosensory scenery provides a simple, yet effective, mechanism for enabling precise compass orientation at any time of the day.