Phoenix is a remarkably young city. The 13th largest city in the U.S. was still an outpost a hundred years ago, but spent the latter half of the 20th century growing at an extraordinary rate while creating an identity for itself as a city with a less than cosmopolitan outlook, but tremendous ambition.

Darren Petrucci, an architect and professor in The Design School at Arizona State University, knows all about Phoenix’s rise to prominence. But his focus isn’t the past. His focus is considering what the city needs to do to prepare itself for the next few decades in order to survive heat and demographic change and internal politics.

Inverse spoke to Petrucci about the future of Phoenix, and here’s what he had to say.

What’s the state of the current infrastructure in Phoenix?

Phoenix didn’t really become a thriving city until the invention of air conditioning. It was fairly inhospitable to live here year-round. The city itself is arguably 75 years old. So our infrastructure is in pretty good shape. The water infrastructure dates all the way back to the indigenous people that were here, who were the Hohokam Indians. They developed the canal system we have. So when we look at Phoenix, the roads are in fairly good shape, the water issue hasn’t yet become an emergent issue in the public’s consciousness, there’s a nuclear power plant to the west, and there’s hydroelectric energy being produced by the Hoover Dam. A lot of the federal funding coming in for infrastructure hasn’t been used necessarily to make new or innovative infrastructure, but it has been used to maintain and upgrade things.

How has the city changed as it has grown?

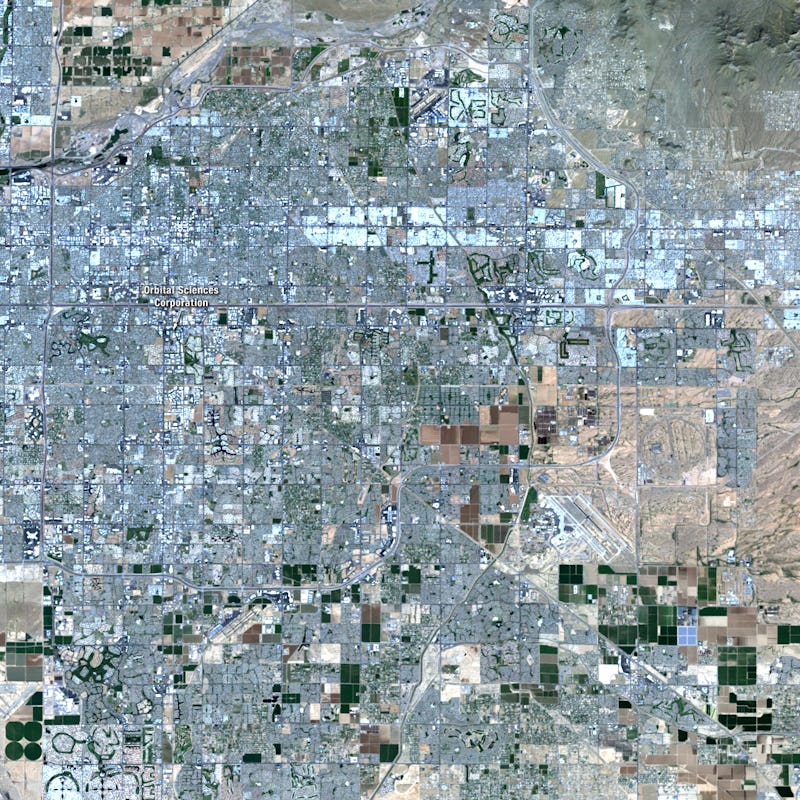

One of the interesting things about Phoenix is how it’s a sprawling city. It’s larger in land area than Los Angeles. It’s around 520 square miles. And that’s largely because of water rights. Unlike other cities that you might fly over, like Boston or Atlanta, where you see small hamlets and villages and towns and then the city, here there’s just literally nothing — and then all of a sudden you see this city. It’s because you have to be connected to the grid. You have to be connected to the water. You can’t just jump out in the middle of the desert and dig a well. But there’s now a big concerted effort to in-fill now. A lot of developers are starting to do more high-density projects.

But it’s a young city, so we don’t have many of the challenges a lot of old cities have. The freeway traffic isn’t bad, because the grid layout of the city is probably the most relentless of any city in the U.S. It doesn’t divert, there’s only one diagonal road [Grand Avenue], and if a street hits a mountain, it hits one end and picks itself up on the other side of the mountain.

So it feels livable despite being, well, arid?

There are some innovative things done in the metropolitan area. One is the Indian Bend Wash, which is an 11-mile long hydrological corridor that runs down the spine of the city. In the ‘60s, the Army Corps of Engineers was going to turn it into a giant concrete culvert, similar to the L.A. river. And the city said this would be horrible because it runs right down the middle of a long linear city [Scottsdale]. So the citizens and the city convinced the Army Corps of Engineers to turn Indian Bend Wash into a series of parks and amenities that also operate as a water management system. And that was one of the most innovative projects at the time.

Now, L.A. is trying to reclaim their concrete river as a riparian project, and break down the concrete. So things like that are very progressive for the Phoenix area.

What are the changing conditions that will affect Phoenix’s growth in the next 25 to 50 years?

Clearly the three big things are climate change, a rapidly urbanizing area, and water.

With climate change, it’s going to get hotter here. This summer, we had temperatures in excess of 110 degree Fahrenheit for many more days that we have in the past. It’s a dry heat, so it’s not like Dubai where the buildings are sweating.

One of the conditions we experience here is the “heat island effect,” which is where the hard surfaces in the city end up retaining the heat created in the day, and cause nighttime temperatures to go up when that heat is released. So the nighttime temperatures are increasing, and that’s not good. In my opinion, one of Phoenix’s unfulfilled destinies is to become a nocturnal city in the summer. For example, a lot of the peewee football is played at 10:00 p.m. at night, when temperatures are much cooler. It would be interesting to think about a city that switches to nighttime activities more during a part of the year, and shuts down more during the daytime. I think there’s that opportunity, but we have to reduce the heat emitted by the surfaces.

But high temperatures have always been an issue, and the public infrastructure has always been in line or now getting in line with that. When it gets to 110 degrees in New York, people die. That doesn’t happen here. So when it comes an increase in a few degrees in temperature, we’re already prepared for it in some ways.

We’re also going to see more rainfall in the winter. That’s partly because I think you’re going to get warming oceans off of Baha, which are going to create more storms off the coast of Southern California, which is going to come across and hit Arizona.

The challenge is, we don’t have very good rainfall harvesting codes or incentives in Arizona. Last fall, we got half the year’s rainfall in one day. When you get three of the year’s seven inches of rain in one day, that’s not good. The water doesn’t flow back into the aquifers and recharge them — it just flows out the city and down the river.

And then there’s population. When I moved here in 1997, Phoenix was the most rapidly urbanizing city in the U.S. Obviously with the recession, we slowed down, but it’s picking up again. Phoenix — for all intents and purposes — has no natural disasters. Unlike California, where you have mudslides and fires and droughts, Arizona has stability for companies, with 320 days of sunshine. So solar power and those kinds of things make a lot of sense. And we’re seeing more of that happening. But the infrastructure and policies will need to keep up.

Can you talk me through the solutions that we know about?

Rainwater retention is a big thing. We have to figure out better ways to collect that rainwater onsite. We have literally no serious water conservation in Arizona, other than the street trees. If we find ways to conserve water, we can make a big impact for the water we already use.

Reducing the heat-island effect is necessary. One of the most innovative things they’ve done here is to use what’s called rubberized concrete and asphalt. It reduces noise, obviously, but it also reduces the mass of the surface, so the roads retain less heat. But that’s a small change.

Shade is a big deal. It’s becoming more and more of an issue. I’ve worked on projects here where we’ve creating new city details for a shade canopy that acts as signage. If you can imagine every sign in a city like Phoenix acting like a shading device, then you can imagine a shaded city.

What a lot of people don’t know is that it takes less energy to cool than it does to heat. So there are lot of people working on things like desiccant cooling systems. Imagine solar-powered air-conditioners, where you make very hot water using the sun, that you make very cool using desiccant cooling, and create air-conditioning. From a thermodynamic standpoint, air-conditioning could turn out to be a cost-effective process.

Temperature increases are inevitable, if we start to employ smart practices and technologies I mentioned we should be able to adapt our lifestyle accordingly. We just haven’t done any of them yet. We’re Americans, so unfortunately, it takes some type of catastrophe before we start to do those things.

Are there any specific projects that come to mind that you’re really excited for? That you think will meet these challenges?

There’s nothing big right now that I know is in the works, but there are a lot of incremental things happening. There are large infrastructure projects like light rail, which developers like. When you create light rail, it’s permanent. It’s not like a bus system that could be fleeting. Once you put rails in the ground, that increases surrounding property value. The first phase of the light rail was very successful, and I think with the next few phases we’re going to see higher density in-fill development and transit-oriented development around the light rail. That will be the next big thing in Phoenix.

We’re also seeing more places deploy shade canopies over parking lots, especially solar-power canopies. [At Arizona State University] I belive we have more solar than any other university in the U.S. All of this reduces the heat island as well produces energy.

Are there lessons from other countries or cities in the U.S. that could be applied to Phoenix?

I think the country that’s leading the charge on things like climate change right now is Germany. They have supposedly more solar power energy per capita than any other country. They’re leading the world in green roofs and in reconceptualizing the notion of the heat-island effect.

There’s also the Netherlands. I look at them a lot when I think about Phoenix. The Netherlands are all built on completely artificial islands they created. In many ways, Phoenix’s existence in the desert is completely artificial. So looking at how the Netherlands thinks about their infrastructure is really quite remarkable.

That’s the way for us to think about Phoenix. It was technology that helped us to conquer the area and build Phoenix. As we move into the 21st century, we have to look at adaptable technology and infrastructure.