Seiichi Miyake: 3 Ways Inclusive Design Is Revolutionizing Urban Planning

Seiichi Miyake showed that inclusive design makes cities run more smoothly for everyone.

Monday’s Google Doodle commemorated Seiichi Miyake, a little-known Japanese inventor who pioneered the use of tactile walkways to make it easier for visually impaired pedestrians to get around.

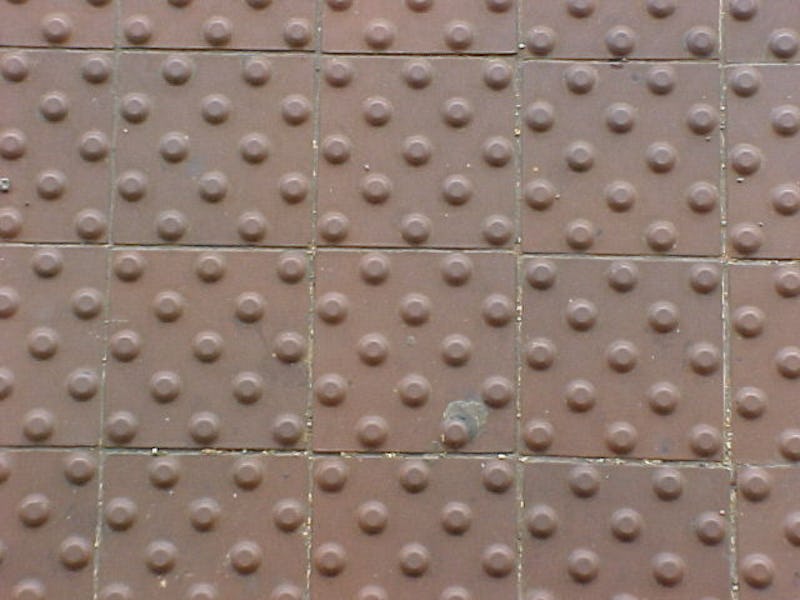

Invented in 1965, the first so-called Tenji Blocks — Japanese for “Braille” blocks — were installed in 1967 near the Okayama School for the Blind in Okayama City, Japan.

By 1984, the Japanese Ministry of Construction issued guidelines making them the law of the land for all transportation terminals and public streets, according to a 2000 paper presented at the Jipea World Congress about Tenji Blocks and their history.

The Google Doodle honoring Seiichi Miyake, inventor of tactile blocks.

Similar laws were later adopted in the United States after the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act, which mandates the use of tactile blocks on all “sidewalks, in all train stations, and on public thoroughfares that coincide with motorized traffic areas.”

The many uses that urban planners went on to find for Tenji Blocks — which Miyake was inspired to develop after a friend began losing his sight — are a perfect example of how inclusive design has been at the foreground of many efforts to make cities run more better for everyone, whether you have a disability or not.

3. Multi-Purpose Walkways

Tactile blocks are a big part of how urban planners are making it easier for people to get around cities without using cars, whose presence can exacerbate pollution, traffic, and congestion.

Developments in New York, Miami, and Dublin, among many others, used tactile pavement to set up efficient lanes for walking, cycling, or wheelchairs, notes the American Planning Association, an organization that promotes “universal” or “inclusive” design.

Retail park in Dublin uses tactile paving to split its sidewalks into pedestrian and cycling lanes.

2. Beacon Navigation Systems

Even with the installation of Tenji Blocks, public transportation hubs — particularly train lines that run under- or above-ground and require stairs to access — can be an accessibility nightmare.

But a new effort in the city of Melbourne, Australia is changing that using Bluetooth beacons and an audio app to help visually impaired customers get around.

As the Guardian reports, users who opt in receive audio cues to help them navigate and also receive alerts if, say, an escalator is broken or out of service.

Anyone who’s ever been a tourist or moved to a new city — and has been forced to navigate sometimes labyrinthine transit arteries — should be able to see how beacon-based navigation systems could be helpful for everyone.

Facebook even tried to develop a special A.I. that could learn to guide tourists around New York City, with mixed results. If Melbourne’s pilot is successful, then, you could soon be braving foreign metro stations with the help of your very own transit guide.

1. Hospitals That Help You Heal

Norway is at the foreground of establishing universal design thanks to a law that pushes the country to make the practice widespread by 2025. As CityLab reported in November, the poster child for this effort is St. Olav’s Hospital in Trondheim.

The hospital instituted a number of inclusive design elements which benefit everyone. Floor to ceiling windows make sure everyone gets enough natural light, and all patients receive a private room.

As CityLab notes, there’s also a path to a garden with different types of terrain for people in wheelchairs to practice on, and the entire hospital grounds are structured to feel more like a small city, instead of a single facility.

Miyake might not be as widely known as he probably deserves. But by proving that urban improvements which seem directed at a tony population can actually benefit everyone, his impact on future cities and their design is sure to be felt for generations to come.