How a Brutal Murder Had a Profound Ripple Effect on Scientific Thought

A viral story of 38 do-nothing witnesses changed sociology, psychology, and neuroscience.

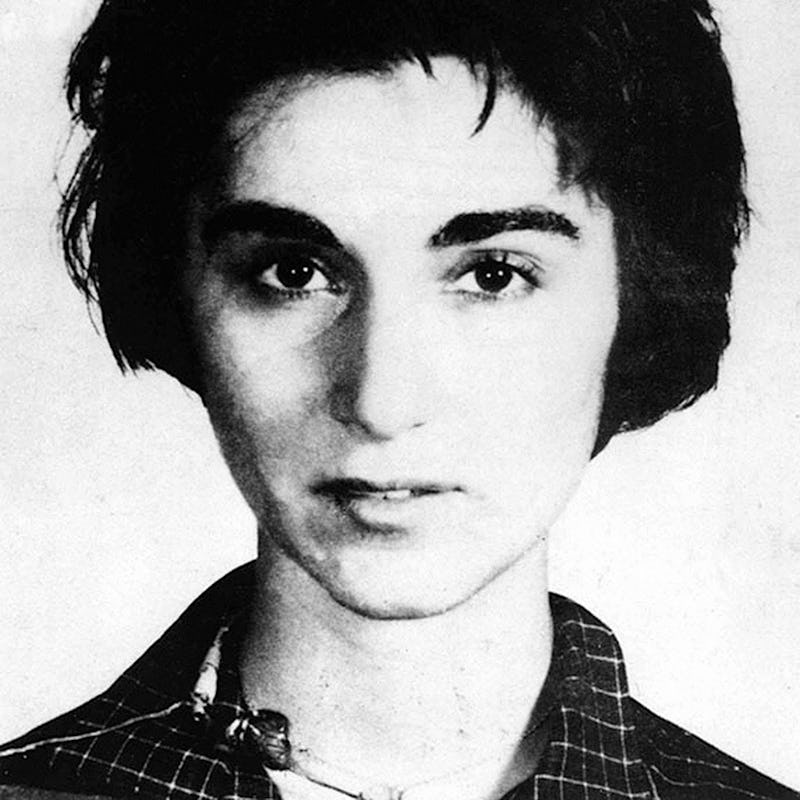

When 28-year-old Catherine Susan Genovese was killed outside her apartment in Kew Gardens, Queens, 38 people reportedly witnessed the attack but didn’t get involved.

Known to her friends as Kitty, she had only lived at 82-70 Austin Street for a year with her girlfriend, Mary Ann Zielonko, before returning on the night of March 13 from her job managing a bar.

Two weeks later, the assault and murder of this charming and bright-eyed woman became headline news.

In his book, Kitty Genovese: The Murder, the Bystanders, the Crime That Changed America, journalist Kevin Cook reports that the 38 figure, which would later prove to be incredibly influential, is inaccurate. “Thirty-eight” was tossed out by New York City Police Commissioner Michael Murphy while at lunch with the city editor of the New York Times, A.M. Rosenthal.

The 38 number was never reported as a lie from the police, and might have been a clerical error that was more reflective of those home at the time rather than people staring in horror from their windows. When Murphy used the number while telling Rosenthal about the capture of the murderer, Winston Moseley, it stuck.

Cook tells Inverse he thinks it stayed with the journalist because of the precision; if the police and the New York Times say it’s 38 witnesses, “one thinks they must know what they’re talking about.”

Genovese’s murder shaped the social dynamic of cities and how Americans are taught to perceive their place as one person within a multitude. Those truths are powerful, even if a key aspect of Genovese’s murder is demonstrably false. The reported refusal of 38 witnesses to help a 28-year-old woman who was being killed on the street started a national conversation about the danger of urban apathy and spurred decades of research on an influential social psychology subject called the “bystander effect.”

Today, 55 years after the Times reported on the crime, it’s clear that while the figure is false, it had a massive impact.

On March 27, 1964, reporter Martin Gansberg reported these facts of the incident in this way:

“For more than a half hour, 38 respectable, law-abiding citizens in Queens watched a killer stalk and stab a woman in three separate attacks in Kew Gardens. Twice the sound of their voices and the sudden glow of their bedroom lights interrupted him and frightened him off. Each time he returned, sought her out, and stabbed her again. Not one person telephoned — the police during the assault; one witness called after the woman was dead.”

Here’s what actually happened:

There were two attacks, not three, as was thought at the time, and as Gansberg’s report reads. Afterward, two people called the police.

A 70-year-old woman held Genovese in her arms until an ambulance arrived, and she died en route to the hospital, not on the street.

More than 38 people were home in the apartment complex that night, but closer to 12 — while not seeing the crime — heard suspicious activity.

A photo of Genovese that appears in the 2015 documentary about her, 'The Witness'.

The myth of 38 was crucial in the virality of Genovese’s story. By the time it was repeated in Life magazine, in the column “The Dying Girl That No One Helped,” the country was in a state of national soul-searching: Was this really a country where people couldn’t turn to help their neighbor?

The police insisted that if someone had called, it would have made a difference. Cook says it’s fair to say that the Genovese case was a significant factor in the rise of Good Samaritan laws, as well as Neighborhood Watch programs and the 911 system.

"Apathy at Stabbing of Queens Woman Shocks Inspector"

The number 38 was also a major influence in the decision to conduct a landmark study, which resulted in the 1968 paper “Bystander intervention in emergencies: Diffusion of responsibility.”

From this study, something called “the bystander effect” emerged — a social psychological phenomenon that posits individuals are less likely to offer help to a victim when other people are present.

Since that first paper was published, evidence for the bystander effect has become more robust and well-replicated; today it’s even seen as a reason why the modern circumstance of cyberbullying persists.

But the replicability of the bystander effect, and the fact that Genovese’s murder was the most-cited incident in social psychology literature until the September 11 attacks, doesn’t change the reality that the initial research was prompted by a false narrative.

“A Diffusion of Responsibility”

In a 2007 paper published in American Psychologist, Rachel Manning, Ph.D., a senior lecturer in psychology at the University of Buckingham, argues that the 1964 murder “paved the way” for the development of the bystander effect, as well as the most influential and persistent account of that effect, “the idea that bystanders do not intervene because of a diffusion of responsibility and that their perceptions of and reactions to potential intervention situations can be negatively affected by the presence (imagined or real) of others.”

Manning tells Inverse it’s difficult to say whether the bystander effect findings would have still emerged if there was no 38 witnesses story. It’s even more difficult to say whether it would have emerged in the absence of the murder of Genovese.

Manning reasons that the lack of evidence for the 38 witnesses story doesn’t detract from the social and psychological research that has been undertaken on the bystander effect since.

Is there value in a falsehood about 38 witnesses who didn’t stop a murder? It might be that it at least creates material for insight into the relationship between social psychology research and the social world in which we live.

A researcher’s framework for understanding the world influences the sort of social psychological knowledge that we gain, and, in turn, attempt to use to create our own framework.

“The form and timing of the story, the nature of the social psychology and social psychological responses it inspired at the time, and how this body of work has developed over time are related,” Manning says. “Interest in a different story of a different event at a different time, or in a different place, would, I would argue, have resulted in a different overall body of work — at least with different emphases.”

Confirmation bias also played a role: The narrative that spread and the research that resulted from it easily slid into a worldview that people wanted, rather than one that existed.

Manning and her colleagues note in their paper that from the 1960s onward, the American Psychological Association called for psychology to promote human welfare and contribute to social life.

At the same time, the suburbs of the 1960s boomed, while social commentators became consumed with concern over an “urban crisis” and the moral heart of the American people.

“I think it’s absolutely right that the ‘moral’ of the myth [of the 38 witnesses] suited a narrative that journalists and social scientists wanted to tell,” Cook says. “It seemed to explain something about urban life — how neighbors in the cold, unfeeling city would watch someone die and make no effort to help.

“The way Rosenthal interpreted, and the Times played it on the front page two weeks after the crime, led to ‘apathy beats’ at other papers, and, of course, the story is still widely understood as a case of apathy on the part of Kitty’s neighbors.”

Kitty Genovese’s story continues to inform the public. Manning notes the presence of the 38 witnesses in many introductory psychology textbooks is problematic, because in the context of a textbook, “such stories tell us about the kinds of problems in the social world that we need to address.”

She suggests the ubiquity of this story has limited the range of phenomena that social psychologists tend to examine in relation to helping behavior.

While there have been many studies conducted on pro-social behavior, a large amount of them operate under the assumed understanding that the presence of others has negative results.

Research on this phenomena, Manning argues, hasn’t necessarily led to practical applications or a broader positive contribution to human welfare. It mostly reinforces what we’ve already presumed.

The discipline of neuroscience, however, could help change the belief that bystanders react similarly. Ruud Hortensius, Ph.D., is a neuroscience and psychology research officer at the University of Glasgow.

He explains to Inverse that for decades, the opinion of the scientific community has been that everyone experiences bystander apathy to a similar extent.

Recent research, including his own, shows that bystanders have different reactions, because they are different people. Refusing to help isn’t a sign of some urban moral failing; it means that a person’s brain processes emergencies differently.

Hortensius explains that the likelihood people will help is a consequence of two opposing cognitive systems, which each lead to different behavioral reactions. The first system becomes active when we see an emergency, typically resulting in inhibition and a freeze-like response. Helping is not very likely. This freeze-up is followed by a slower system that’s not linked to distress but to sympathy for the victim. That’s when a person helps.

The strength of these two systems and reactions is different for each person, as is the balance between the systems.

An emerging view, Hortensius explains, is that the medial prefrontal cortex plays a crucial role in determining whether an individual will help or not. It provides the link between a situation and a response, and signals the appropriate action.

This means that the bystander effect is a result of a reflective action system rooted in an evolutionarily conserved mechanism in the brain, not an apathetic reaction.

"Bystander apathy is not due to a lack of responsibility."

“These studies tell us something different than decades of research on bystander apathy have told us,” Hortensius says. “Bystander apathy is not due to a lack of responsibility, or fear of being judged, or a belief, but a consequence of reflexive emotional reaction.”

Research on bystander apathy, he argues, has ignored what goes on in the mind of the the bystander. When you read that a man told the police he didn’t help Genovese because he “didn’t want to get involved,” it’s easy to make presumptions about his — or urban society’s — failings. But we don’t actually know what was going on under the surface of his consciousness. We are, meanwhile, beginning to understand that he doesn’t reflect the rest of us.

Genovese’s story can still inform and influence our lives, but it needs to be the right story. Manning explains that the purpose of her paper was to “broaden the imagination around the social psychology of helping, and stimulate different ways of thinking about it.”

Scientists argue that it’s important to critically interrogate the information we’ve taken for granted, especially in areas that have a potential for application. At the heart of it all is a senseless tragedy and the death of a 28-year-old woman 55 years ago. But people will always be called on to help, and we’re still in the process of understanding if and why that help will come.

Email the author: sarah@inverse.com