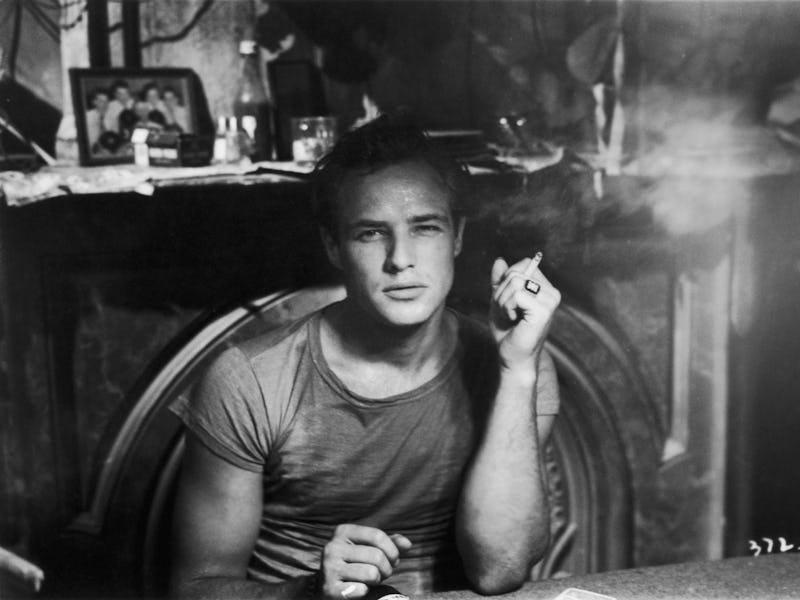

'Listen to Me Marlon' Gives Us Brando in His Own Words, No Explanations

How the filmmakers behind the documentary 'Listen to Me Marlon' wrestled with Brando's private life.

How do you put Marlon Brando in context? This is a question that has baffled more than a few scholars. Hollywood’s most dangerous leading man made it as hard as he could, treating the press, directors, and intellectuals with equal parts disdain, anger, and sensitivity while erecting a wall around his personal life. With Listen to Me Marlon, a film constructed from recently uncovered home recordings made by Brando beginning in the ‘50s until his death in 2004, Stevan Riley jumps that wall. But what he finds on the other side — philosophical musings, banal chit-chat, repetitious meditation — does little to cohere the Brando narrative. The tapes give us a portrait as contradictory as the public persona and the sense that this truly was a troubled artist.

Riley’s film is less eulogy than deep-dive into Brando’s psyche, told by the actor himself from the more than 200 hours of material the filmmaker and his team were given access to by the Brando family board of trustees. “I was terrified because it hadn’t really been done, telling a story in the voice of a deceased person,” Riley told me at the offices of Film Forum in New York. “We didn’t know how many tapes were going to come out. Nothing had been transcribed. We didn’t know what was on the tapes.”

As soon as he began listening to the tapes, the film began to take shape. “I thought it would actually be a cleaner way through the story and in answering that question, Who was the real Marlon Brando?” he said. “Who better than Brando to answer that himself?”

That angle helped Riley get over the stigma of potentially uncovering something the actor didn’t want to make public. “I mean, I’m pretty private. It’s a nightmare to think that someone would go and riffle through your stuff with or without permission,” he told me. “The only things that kept me going and really gave me a focus, in terms of my research and what to achieve with the film, was that Brando really did feel he had been misrepresented through his life.”

Director Stevan Riley

Riley: “The idea was that if Marlon had a bunker where he’d store all of his tapes or documents, the lot, that he was pulling it out of the bunker and trying to sort out his life in his house from beyond the grave and just figure out the person he was and how his life had arrived at that time.”

Riley edited the movie by using an Excel spreadsheet with more than 400 tabs to keep the theme of each tape in order. He came up with a poetic stream-of-consciousness form for the film — one that weaves and criss-crosses in a semi-chronological fashion that ties itself to the themes that defined, and haunted, Brando throughout his life. Fame, fortune, infamy, childhood. Nothing was left out.

Yet the big moment in the film that stands like a dark monument, marking the time later in his life when he became more self-reflexive than his earlier, more rebellious days, was the conviction of his son Christian for murdering his sister Cheyenne’s boyfriend, and her subsequent suicide. “After the tragedy, my dad had to find a way to deal. He had so much going on,” Brando’s daughter, Rebecca Brando, told me. “He had 10 children, and having to take care of an island, and take care of all the families, and his work, and dealing with many other different things in his life, he had to find a way to slow down.”

To the heartbroken Brando, going inward was the only way to cope, which was a contradictory move from someone whose controversial behavior on movies like Mutiny on the Bounty or Apocalypse Now made Hollywood shun him as much as he shunned it. But Brando’s daughter says it was an intentional move on her father’s part, whether he was conscious of it or not. “There’s the side of my dad who’s very mystical and an enigma, and there’s the side of him that he is in the public eye, she said. “So if you’re recording something, it’s obvious that somebody, somehow, someday is going to find it.”

The tapes were perhaps the only time Brando could wipe away the artifice of fame towards a feeling of clarity. “He was just so raw with how he was like, ‘Hey, you may think I’m this big great actor, but I’m just like you and I. I want to still be accepted, and approved, and validated. I am a contender,’” Rebecca Brando said. “And I thought that, for a man of his status and stature to say those very kind of insecure sort of things, you’re surprised.“

But that doesn’t necessarily mean he came any closer to the truth he sought. What makes Brando’s words and the film so resonant is his continued fight between the silver-screen titan and the dejected man talking, alone, to himself. “People will mythologize you, no matter what you do,” Brando says on one of the tapes in the film. And later: “It removes you from reality. I hate it.” There may not have been any easy answers, but there was catharsis.

“He says at the end that he feels like he’s come close to the common denominator of what it means to be human,” Riley said. “There’s this one thing that does reverberate through the film, that he just realizes the duality, the ability to hate, the ability to love, the ability of good people to do terrible things, and probably the idea that he wasn’t a bad person but he’d sinned in his life.” Riley saw the tapes as a way to balance his public versus private image. “How much control do we have? How much ability do we have to effect or own behaviors after nurture and genetics and all of this kind of stuff,” Riley said. “He was wrestling with it.”

The biggest misconception going into Listen to Me Marlon would be to assume it will provide easy answers. Rebecca, however, was hopeful that by creating such a personal record, he might inform others reeling from personal troubles.

“He always wanted to make a mark,” she said. “He always wanted to do something bigger than just being an actor, because he didn’t qualify that as being a measure of being just a great person. He really wanted to change the world, and so I think that by making this film, you could see the human side of him, and if it inspires people and gives them insight as to how to be okay with themselves, then that would be just enough for him.”

Listen to Me Marlon depicts Brando as a consummate artist. He constantly questioned human behavior, whether by rewriting an entire script to suit an onscreen character or by reminiscing in solitude in his living room before his death. The film ends with a sort of self-hypnosis from Brando, a repetitious call for calm amongst the unknown. It’s a perfect ending for a man who, even after this revelatory work of raw disclosure, remains a mystery.