Scientists Uncover Which Facebook Posts Might Be Signs of Depression

"Online language, just like offline language, often reflects who one is."

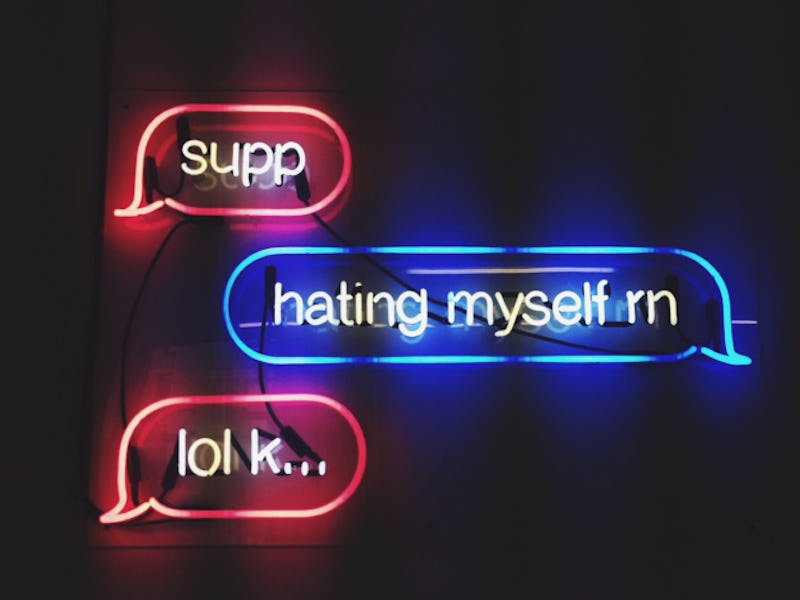

Every day, people post their most personal thoughts on their Facebook feeds, entrusting the internet with information they may never confide to an actual person. While those posts may seem like meaningless noise to other users, the authors of a new Proceedings of the National Academy of Scientists study discovered they were digital cries for help. Hidden in the language of these posts, they found a way to identify users struggling with depression, even if the users themselves don’t know it yet.

Now, when people cast their thoughts into Facebook’s void, an algorithm can listen in for meaning in their musings. The paper, written by Stony Brook University computer scientist H. Andrew Schwartz, Ph.D., and University of Pennsylvania post-doc Johannes Eichstaedt, Ph.D., describes how a new algorithm can predict future depression diagnoses by identifying certain key words and phrases that people use in their Facebook status updates.

“Depression effects many aspects of one’s life. I’m not so sure it’s people reaching out as much as it is just that online language, just like offline language, often reflects who one is or the state they’re in,” Schwartz tells Inverse. “The words indicative of depression suggests both that people are reaching out with how they feel, but there are also differences in style that seem less about reaching out, such as greater use of self reference (‘I’, ‘me’).”

Some of the most common words and topics found in the facebook posts of people 6 months before they were diagnosed with depression. Larger words indicate that they were more common.

They tested their algorithm by analyzing the Facebook posts from 683 users in an urban metropolitan area, 114 of whom were eventually diagnosed with depression by doctors, as medical records confirmed. In particular, they analyzed the content of the posts made prior to each user’s diagnosis to assess whether a person’s social media presence could predict who was already struggling with depression and to test whether the depression-predicting algorithm really worked.

In those records, they found changes in the way depressed individuals used social media. They tended to use more first-person pronouns (I, me, myself) more than those who were not diagnosed with depression. These people also often complained of physical symptoms through Facebook posts, commonly using words like “hurt,” “tired,” “head,” and “bad.” In addition, they used more words that indicated rumination, like “scared,” “mind,” and “worry.” Rumination is a marker of depression defined by obsession about details that eventually leads to persistent and crushing anxiety.

But perhaps most telling is the fact that the posts from depressed users tended to be far longer than those from non-depressed users. Per year, depressed users wrote an average of 1,424 more words across all posts.

Tools like this are powerful because they can prevent people silently struggling to keep their heads above water from getting lost in the anonymity of social media. The new algorithm doesn’t address people who would rather confide in a different platform, like Twitter or Instagram. but Schwartz says this algorithm can be adapted to other social media platforms as well.

“Facebook is used much more frequently by the average person in our population, so it provided more data,” he says. “On the other hand, there are methods to ‘adapt’ a model built on Facebook to other social media domains and we could train a model from scratch for that domain and, from past work, I would expect it to work nearly as well.”

Right now, they’re sticking to Facebook, looking to increase accuracy. But this trial run demonstrates one thing: the people have spoken. It just took an algorithm to really understand what they were saying.

Significance:

Depression is disabling and treatable, but underdiagnosed. In this study, we show that the content shared by consenting users on Facebook can predict a future occurrence of depression in their medical records. Language predictive of de- pression includes references to typical symptoms, including sadness, loneliness, hostility, rumination, and increased self- reference. This study suggests that an analysis of social media data could be used to screen consenting individuals for depression. Further, social media content may point clinicians to specific symptoms of depression.

You May Also Like: Your Brain On Social Media