On NASA's 60th Anniversary, Its Biggest Priority Is the One It Started With

Space history has come full circle.

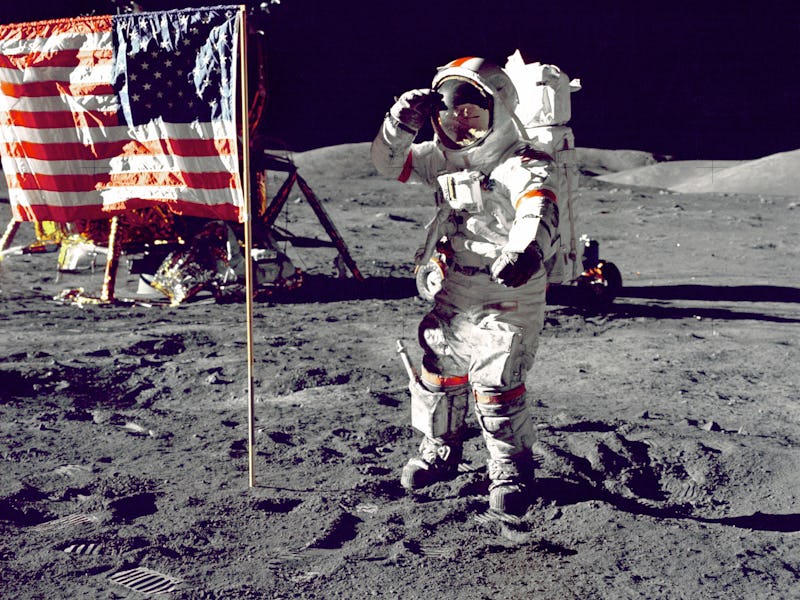

On October 1, 1958, the inauguration of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration marked the beginning of history’s first space race. The creation of NASA was a direct response to the launch of the Soviet Union’s first Sputnik satellite into orbit in 1957, but it wasn’t long before the race was on to get humans into space. NASA achieved that goal with four human spaceflight programs between 1959 and 2011, but since the Space Shuttle Atlantis was retired seven years ago, Americans haven’t been able to get themselves off the ground.

But US astronauts won’t remain flightless for much longer, predicts renowned space historian and “Dean of Space Policy” John Logsdon, Ph.D., thanks to renewed interest in deep space exploration, the deep pockets of private spaceflight companies, and, perhaps, an ongoing sense of embarrassment.

“I think that’s going to change in the next decade and NASA will be an agency focused on exploration — sending people beyond Earth orbit, back to the Moon, onto Mars,” Logsdon, also the editor of the new Penguin Book of Outer Space Exploration, tells Inverse.

“I think NASA has a potential for having a kind of renaissance, and I think a little more money. We’re going as we can pay for it. But I think the goal of the government human space flight program is now back to sending people away from Earth to go to explore new places.”

The Renewal of Interest

In recent years, Hollywood has reflected — and fed forward — a renewed public interest in space travel. Blockbuster films like Interstellar, Gravity, and Passengers could prove to be more prescient than their sci-fi roots suggest.

In late September, NASA unveiled its campaign to return to the moon, called the National Space Exploration Campaign. According to NASA, the campaign “calls for human and robotic exploration missions to expand the frontiers of human experience and scientific discovery of the natural phenomena of Earth, other worlds and the cosmos.

The Rise of Private Spaceflight

Of course, getting Americans back into space won’t be possible without money, which Congress hasn’t provided (NASA’s budget is currently around $20 billion.) “We’ve been working on it since 2010,” says Logsdon. “It’s taken too long because Congress has not provided adequate funding, but we’re very close.”

The reason Logsdon, who has chronicled NASA’s successes and failures over the past half-century, can be so optimistic is because the new era of human space exploration will largely be funded by the deep pockets of the private sector. “I think the renaissance will be very different. It will be the private sector doing ambitious things,” says Logsdon.

“SpaceX, Elon Musk’s company, and Boeing, within the next months, are supposed to demonstrate their new spacecraft that will carry crew to the Space Station.” In August, NASA unveiled its “Dream Team” of nine astronauts who will be the first to fly to the International Space Station on both Boeing’s CST-100 Starliner and SpaceX’s Crew Dragon.

The Embarrassment of Flightlessness

These days, whenever the US wants to send astronauts to the International Space Station, where America is the majority partner, it must cough up between $70 million and $80 million to Russia’s ROSCOSMOS for a ticket to ride on a Soyuz spacecraft. Since the space shuttle Atlantis was retired in 2011, NASA simply has no way of getting people into space, while Russia and China do.

“We’re supposed to within the next year regain that ability that we lost when we retired the shuttle in 2011,” says Logsdon. “But it’s a bit of an embarrassment [for a country] that thinks of itself as the leading space power not to have that capability.”