An Eye Infection Found in Contact Lens Wearers Can Cause Blindness

"It's a shitty disease to get."

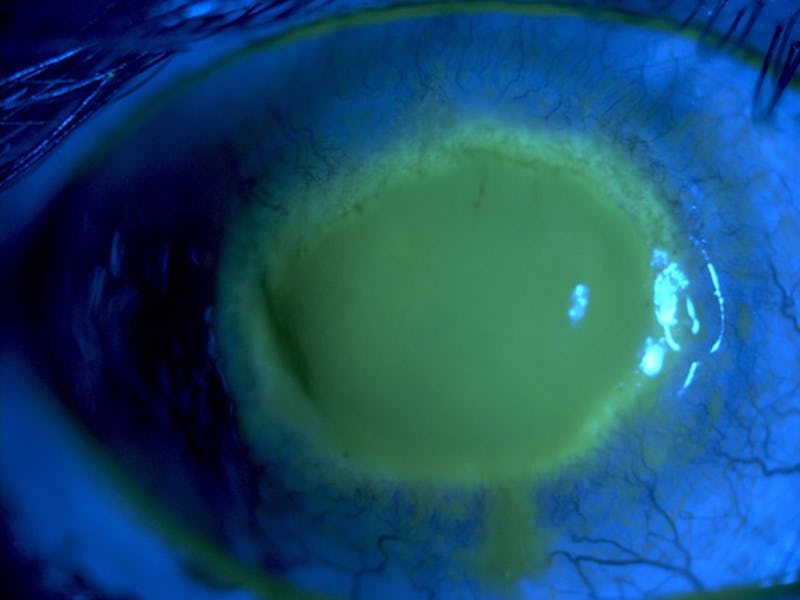

A group of ophthalmologists recently identified an outbreak of Acanthamoeba keratitis, a nasty amoebic infection that can cause painful cysts and eventually blindness. To avoid it, contact wearers should probably change up their morning routine, the doctors suggest in a paper published in the British Journal of Ophthalmology.

Acanthamoeba keratitis is a rare infection caused by exposure to Acanthamoeba — a microorganism that can survive between the contact lens and the eye, forming painful cysts. In about a quarter of Acanthamoeba cases, patients lose up to 25 percent of their vision or go completely blind from the infection, explains study co-author John Dart, MD, of Moorfields Eye Hospital in the UK.

“It’s rare, but it’s a shitty disease to get,” Dart tells Inverse. “We only get 70 percent cured in twelve months using the best available treatments. It’s one of the worst eye diseases to get, and they’re in all young people. It’s painful.”

Acanthamoeba keratitis can cause blindness in some severe cases

Data collected in the new paper shows that the number of patients at Moorfields with this infection has nearly doubled in recent years: in 2011 there were 36 reported cases, but by 2013 this number had spiked to 65. Elsewhere in London, other practitioners noticed it too:

“We have a sort of corneal group here and an email went around saying ‘We think we have a problem’. We realized when we started looking at our own figures that there was indeed an outbreak,” he says.

In England, these amoeba tend to thrive in water tanks, hot tubs, and swimming pools, basically anywhere that a biofilm — a slimy colony of cohabitating bacteria— can stick to a hard-to-reach section of pipe. So imagine this: Each morning you put in your contacts and jump in the shower. When you turn on the tap, you may be welcoming these tank-dwelling amoeba into your home.

“We think it’s likely that it’s the water exposure,” Dart says. To avoid contaminating your lenses, avoid washing your face, or at least dry your hands before handling your lenses, Dart says. “Don’t shower in them or go swimming in them or sit in a hot tub. If you do, take them out and throw them away. If you do those things, we think 90 percent of cases would probably go away.”

Dart is also adamant that contact solutions touting disinfecting ingredients are far from enough to stop the spread. Most contact solutions do include an effective Acanthamoeba-killing ingredient, Polyhexanide (PHMB) but there are some bacteria and amoeba that may survive that PHMB purge.

“These disinfectants are not sterilizing agents. In a contact lens case, that bacteria can build into a slime layer,” he says, also adding that often one or two amoeba will likely survive a bath in disinfectant solutions if the case is old or already dirty.

Cases of Acanthaamoeba keratitis at Moorfields Eye Hospital in London

That’s why Dart and his colleagues suggest that the best way to avoid this infection is to keep your contacts water-free — or switch to daily lenses where, even if they do get infected, you dispose of them before the amoeba have time to take root.

They’ve also created a “no water sticker” campaign that they hope will eventually be adopted onto all contact lens packaging. While most contact lens providers provide inserts in their packaging that list potential risks, Dart says he would like to see the dangers of water contamination take the forefront.

“It’s a simple sign, a tap with a cross through it, to draw people’s attention to the fact that they should avoid water when using contact lenses,” he says. “That’s what all manufacturers are telling everybody because they’re aware of our research, but they won’t make this clear.”