Scientists Learn Why Some Animals (But Not Humans) Still Have a Penis Bone

It's a shame we lost ours.

Of all the euphemisms we have for an erection, “boner” is one of the most common. It’s also, at least for humans, an egregious misnomer. Any person who’s ever encountered an unexcited human penis before knows that it has no bone. Some animals, however, do have bones in their boners, and a new study in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B offers a compelling explanation for the function of the penis bone, or baculum, in those species, shedding some light on why humans have lost theirs.

In the paper, Manchester Metropolitan University researcher and lead author Charlotte Brassey, Ph.D., uses 3D computer models of animal penises to argue that the animals that do have a baculum have one because of a particularly impressive characteristic of their sex lives. While previous research on the baculum suggested that the bone evolved to help relatively large penises get into relatively small vaginas, the work of Brassey and her team shows that it’s far more useful in helping the penis safely stay put once it’s in — occasionally for quite long periods of time.

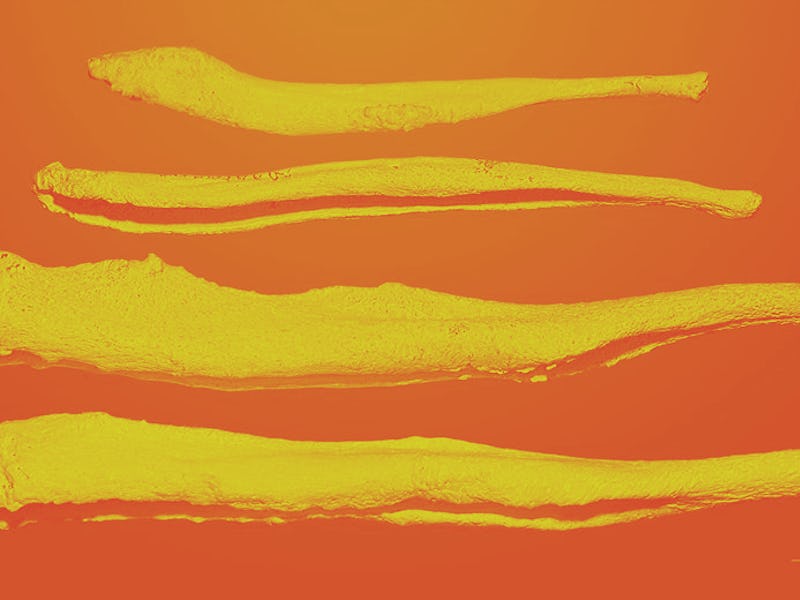

The baculus of a sloth bear.

“The ‘vaginal friction’ hypothesis,” Brassey explains to Inverse, referring to one theory for the function of the baculum, “is based on the idea that the rigid baculum bone might help stiffen the penis and assist with the males overcoming the friction associated with a smaller female vaginal tract.” But her new data on baculum strength, which didn’t show much of a difference in species where the male is much bigger than the female, don’t support this theory. Rather, her data support a different theory called the “prolonged intromission” hypothesis.

It is what it sounds like: Prolonged intromission refers to the amount of time a penis is in a vagina. Brassey’s work suggests that the baculum’s size and shape developed in order to help penises stay in place, avoid getting the urethra squished, and help sperm delivery during longer intromission durations. More broadly, the stronger the baculum, the longer the intromission. (Some animals, like the coati — a member of the raccoon family that definitely has a baculum — have an intromission duration as long as one hour.) The data suggest that the physical characteristics of the baculum evolved to help the penis stay in throughout the duration of copulation.

Coatis: Have long sex and a strong baculum.

Collecting this data involved creating virtual animal bacula and seeing whether they (quite literally) folded under pressure. “In the past, authors have only looked at metrics such as length and diameter. Our study is unique in considering the behavior of the baculum as a whole single ‘entity,’” says Brassey. “[We] create 3D models of the whole structure, including any bizarre ridges, curves, grooves that they possess.” After that, she says, they “virtually crash-test” the modeled bacula to see how they behave when forces (say, the walls of a vagina) are applied to them.

Taken together, the team’s data show that the longer a species’ intromission duration, the greater the strength of its baculum. “Our results support the notion that the size and shape of the carnivoran baculum have evolved in response to selective pressures on the duration of copulation and the protection of the urethra,” they write.

Compared to that of the impressive coati, human intromission duration is pretty short: In a 2005 study in the Journal of Sex Medicine of 500 couples around the world, the median duration was 5.4 minutes — though the range, admittedly, was pretty huge (one couple reported 44 minutes). It’s too early to say, however, that our quick finishes led to the loss of our bacula. “The reasoning why humans don’t have a baculum is still a bit of a mystery,” says Brassey.

A walrus baculum.

All the other apes have a penis bone, she explains, but even theirs are only about the size of a grain of rice and occur only in the head (glans) of the penis. “However, during erection, the glans is not as blood-filled as the ‘shaft’,” she continues. “So this means in species with much larger glans (such as dogs and bears), they rely more on the rigid bony support of a large baculum, compared to the hydrostatic ‘blood based’ rigidity of the shaft during erection like in humans.”

In 2017, another paper in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B similarly argued that the baculum evolved for prolonged intromission duration. However, the authors of that study took the argument a step further by theorizing that the reason humans lost their bacula is because they developed monogamous relationships, and so a human male no longer needed to resort to a literal bone to make sure his penis stayed in his mate long enough to get her pregnant.

The baculum largely remains a mystery, just as it did when Brassey first started her work. “Honestly, I was sat in a scientific conference and during their talk, one of the speakers briefly mentioned the baculum as an aside, and the fact that no-one could agree on what the baculum is actually used for,” she says.

“This just struck me as fascinating, the fact that there could be a bone that is so common across mammals, but we can’t figure out how it functions. With my background in 3D modelling and anatomy, it seemed like the kind of question I could help answer!”