Drake, Meek Mill, and Hot 97: A Brief Guide to Hip-Hop’s Lamest Beef

Last night, the public dispute between Drake and Meek Mill took a turn for the absurd.

We at Inverse have been respectfully avoiding covering the controversy surrounding last week’s claims, made by Philadelphia rapper Meek Mill on Twitter, that Toronto rapper and former Degrassi star Drake frequently uses ghostwriters. The ensuing debates and clap-backs have remained steadfastly boring for days. However, in the past 24 hours, the tedium has transformed itself into self-parody, so it felt like the right time to give it a look.

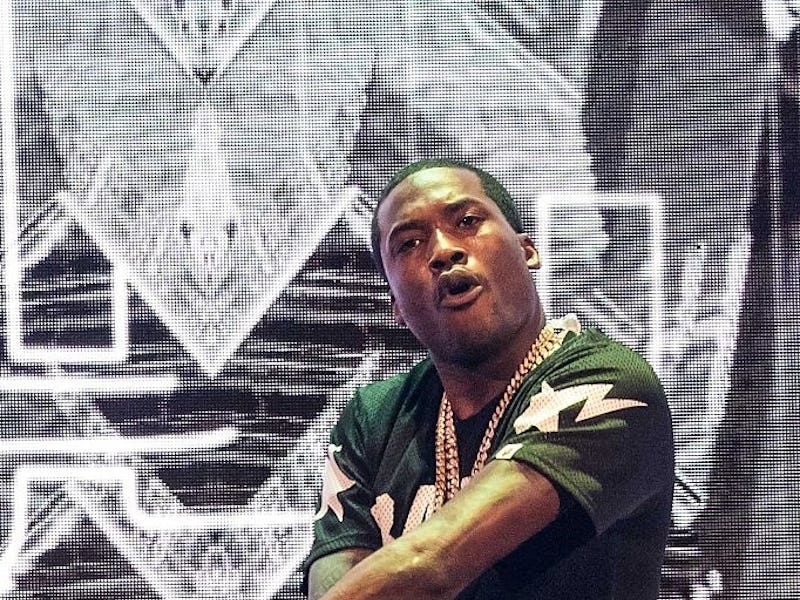

Mill’s accusation came amidst one of those not-infrequent diatribes about the State of the Rap Game Today and Reals vs. Fakes, which periodically crop up — usually, on the timeline of some aging East Coast rapper who wants all the Bill Cosby slander to stop and thinks that Joell Ortiz is the greatest working MC. Meek Mill, on the other hand, is one of the most technically gifted and high-profile street rappers in hip-hop today. He recently released a relatively successful new album and is now on tour supporting his girlfriend, Nicki Minaj.

Mill’s takedown, therefore, made headlines; Drake, after all, is Minaj’s labelmate and frequent collaborator. Meek’s most astonishing claim was that the verse Drake contributed to his new album (“R.I.C.O.”) had been written by someone else. If he had known at the time, Meek said, he would have scrapped it.

The casual accusation set off a minor social media shitstorm. The fallout included a response from Drake’s producer and co-architect of the Drake brand, Noah “40” Shebib, who disputed the emerging claims that rapper Quentin Miller (aka “Q”) was a ghostwriter for Drizzy. He concluded by shaming #TeamMeek for “questioning [his] brother’s pen.” Q himself then denied his involvement as anything other than a marginal collaborator.

What became painfully clear was that Mill was just not using the term “ghostwriter” accurately. Drake’s collaborators are rigorously credited in his liner notes. Perhaps Meek was simply making the point that no one reads liner notes these days, so that the effect, in essence, was the same as ghostwriting — a fair point.

Of course, Meek’s argument plays into a institutionalized view of the locus and ideals of hip-hop music. However, ghostwriting has been prevalent in rap since the days of the Sugarhill Gang and Rapper’s Delight, the record that was hip-hop’s big international breakthrough. On the song, member Big Bank Hank delivered lines borrowed uncredited from Bronx MC Grandmaster Caz. There were larger “authenticity” issues also: Sugarhill Gang was a group formed by a record company, after all, not a unit pulled straight from New York-area MC parties.

There have been countless other minor scandals. There was Ice Cube’s ghostwriting for Eazy-E’s N.W.A., and a collaborative authorship that produced The Chronic. Later, one of hip-hop’s post-Golden Age icons, Notorious B.I.G., received a musical tribute from his impresario and collaborator — the artist formerly known as Puff Daddy — in the form of a Police-interpolating song which was actually scribed by low-profile rappers Sauce Money. This would go on to hold the record for longest-running rap single on the Hot 100.

But blah and blah: These examples have been debated before. It’s part of what makes the fallout from Mill’s accusations so mindnumbing. It makes sense that Meek would uphold the importance of untarnished self-expression in hip-hop; his is a particularly potent brand of “reality rap” that speaks to his own experiences growing up in Philadelphia. These stories have distinguished him as an artist. Authenticity is part of his specific ethos and enhances the potency of his work.

But what has been most humorous here has been observing the supposed public faces of New York/”real” hip-hop uphold or debate Meek’s worldview, as if it should be accepted as objective fact. Storied DJ on NYC’s Hot 97, Funkmaster Flex, a few nights ago, came out with guns ablazing against Drake, claiming to have “reference tracks” for several of the rapper’s songs and disparaging him for his non-transparency. “This ain’t about Meek or Drake… This is about an art!” he tweeted in the midst of a generally confusing rant. “Dre, Diddy, Kanye, Drake, Timbaland !!!!! In that fucking order!!!!” he ended, as if Flex was providing the definitive ranking of the ghostwritten rap figures. It was impossible to know what he was talking about.

Last night, Meek was to drop by Flex’ show to drop a diss record in response to Drake’s holier-than-thou and periodically sexist subtweet record “Charged Up” (whose most incendiary line, perhaps, was apparent Nicki reference “Rumor has it, I either fucked her or never could”). Rap devotees tuned in to the station for two to four hours waiting for the fire-spitting response from the MC whose signature is spitting fire (see the aging “Meek Mill rap like…” meme). Meek did not attend Flex’ show, but took to Twitter to release a short video of him playing a 15-second clip of hyena-like laughter entitled “Beautiful Nightmare”:

The prank incited a bizarre slew of responses. New York rap conservatives disparaged Meek’s dismissive gesture. NYC producer Statik Selektah called it representative of the “social media gossip non rapping ass era” and some “love and hip hop shit.” Trad-minded podcaster Taxstone excoriated the Hot 97 staff on Twitter (morning show host Ebro lied about his wife going to Harvard! What a bunch of fakers and cheats!). A charge.org petition emerged, arguing that Funkmaster Flex should step down at Hot 97 because he had “[lied] to everyone for ratings and downloads.”

Hot 97 has had a rough past year and a change. The personality that contributed the most to the station’s exalted standing in the hip-hop community — host and interviewer extraordinaire Angie Martinez — left for rival station Power 105.1 after almost thirty years of service last June. Longtime DJ Cipha Sounds followed suit in January (he was fired after publicly criticizing the station).

Part and parcel to Flex’ legacy has been premiering new music exclusives — diss tracks and otherwise — as well as holding down one of the most popular hip-hop mix shows in history. Last night’s events again raised the question, which has been percolating in all corners of the hip-hop community for some time: With programming on Hot largely determined by Clear Channel stats and focus groups, and New York no longer hip-hop’s most influential hub, what is the real use of Flex, or any of them? Power 105.1’s staff from DJ Envy to Charlamagne da God — who gave Funkmaster Flex his traditional “Donkey of the Day” award for his fakeout with the Meek track — took the opportunity to gloat about their rival station’s latest misstep. Hot 97’s Ebro dismissed Power with the time-tested auto-response: “When anything important in hip-hop happens, it happens on Hot 97.”

As a humorous epilogue, the world was gifted with an unambiguous, full-throttle diss track from Minaj’s former boyfriend Safaree, reacting to the controversy, and shots Meek had taken at him in the past. The track recalled the aftermath of Kendrick’s verse on Big Sean’s “Control” in 2013, in which he declared facetiously that he was the “King of New York,” and a slew of minor rappers who Kendrick had not mentioned in the song — and probably had never heard of — came out with stodgy and unintentionally comic response freestyles.

In the Meek diss, you could practically hear the moments Safaree imagined his audience letting loose an “Oh shiiiiiit,” (anything from “My dickprint, lil n——, you can never match” to “Here’s an iron, n——/ ‘Cause you look preeeeessssed”) but probably more of his audience was too busy Googling him.

Some people measure the quality of hip-hop by the “bar,” and others by the standards of almost any other popular music: the final, overall product. The idea that there is one way to view the core of any art form, or ascribe value, is a misunderstanding that has cropped up and caused tension throughout history. This debate in particular brings to mind the Wynton Marsalises and Stanley Crouches of the world who deemed (or still deem) Miles Davis’ brash, rock-festival-ready electric music of the ‘60s, ‘70s, and ‘80s non-jazz. Jazz, to them, is measured in units of “chops” — by the power and unity of the “solo.” But Miles, like Drake and hip-hop’s most reliable vanguardist and avid collaborator, Kanye, envisioned the overarching sound first and foremost. These artists assume a role as bandleader more than anything else; the trumpet player or the rapper becomes just another sonic puzzle piece.

This is not to claim that the Drakeians are more “right” than the Meekians; there is no “right” when it comes to matters of taste, and I don’t even think Meek would agree with most of the “Meek”ians. There is discourse, and then there is sound itself, which is manifold and irreducible. Beefing over musical epistemologies makes mostly for good comedy. It’s easy to see the standpoint Meek was coming from by sidestepping the whole debate with his joke track, even if he did start the whole thing in the first place.