Researchers Have Developed a New Way to 3D Print Using Metal Composites

A very metal discovery.

Equally as important as the hardware and the software that powers them are the materials you put inside a 3D printer to bring your vision to life. All sorts of experiments are underway to find ways to improve upon the thermoplastic that’s typically used, which can be flimsy, from ceramics to metals to new materials entirely.

3D printing using metal is obviously one priority of researchers, who have long seen 3D printing’s potential to revolutionize prototyping, allowing inventors to rapidly iterate upon components and new parts and more quickly get them into the real world. But the methods we have so far are laborious and costly, requiring the use of powdered metals and elaborate support structures to mold your composite into the desired shape. Thankfully, a team of researchers working with a company called Desktop Metals think they have a workaround.

“We have shown theoretically in this work that we can use a range of other bulk metallic glasses,” explained Jan Schroers, a professor of engineering and materials science at Yale, in a statement. “[We] are working on making the process more practical- and commercially-usable to make 3D printing of metals as easy and practical as the 3D printing of thermoplastics.”

Their research was just published in the journal Materials Science.

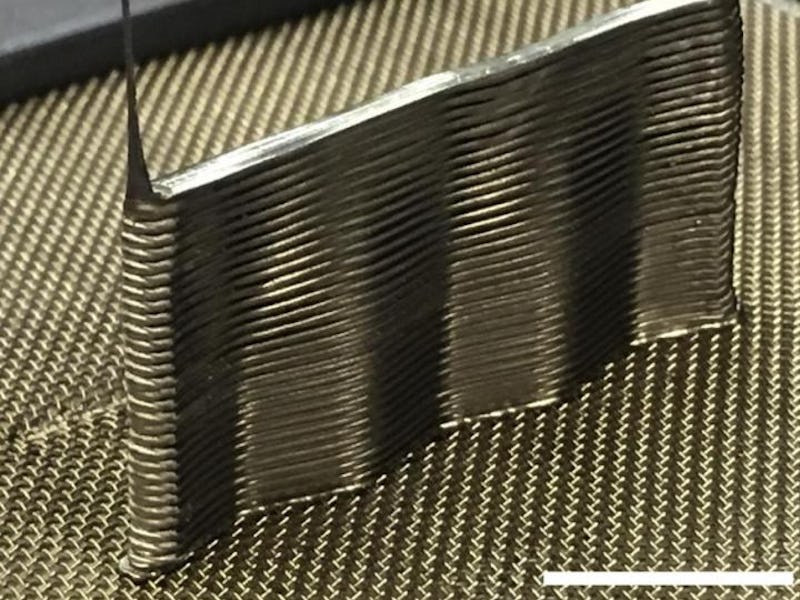

A new method for 3D printing structures using metal by quickly heating and cooling it as it gets incorporated into the greater structure.

Why Is 3D Printing With Metals So Hard?

There’s a reason why thermoplastic is the material of choice in 3D printing despite its shortcomings. It cools quickly, is super malleable, it doesn’t cost very much, and efforts are underway to make the composites even stronger. But they’ve obviously not nearly as strong as metals, which are super tough but can’t readily be “extruded” (the process of shaping something by forcing it through a shaped die, kind of like how fancy bakers make decorations by squeezing frosting through a piping bag).

This new approach gets around those problems by fusing metallic bulk glass filaments (also referred to as amorphous metals) into the metal objects being designed. Metallic glass is much easier to soften and manipulate than conventional metals. The study used a mix of beryllium, copper, nickel, titanium, and zirconium.

The metal was then heated up to an extrusion temperature of 460 degrees Celsius, and then fed through a heated mesh made from stainless steel to prevent crystallization from occurring to rapidly. The final parts of the extrusion process were then carried out by a robot.

In order for their method to enter the mainstream, researchers say that the raw materials they used should be made more widely available. Their technique also requires some refining, they say, before its ready for commercial use.