Three Ancient, Unheard-of Species Are North America's Lost Primates

Their kind doesn't exist in North America today.

Millions of years ago, San Diego was without shopping plazas, surfers, and burritos. But it was warm — even more so than it is now. During the Eocene epoch, some 45 million years ago, San Diego’s hot climate ushered in lush forests across what would become the beach city and deeper into North America. Those forests were home to ancient primates, three of which researchers had never heard of, report scientists in a recent study in the Journal of Human Evolution.

University of Texas at Austin graduate student Amy Atwater and anthropology professor Chris Kirk, Ph.D. announce in the paper that these three extinct primates died between 42 and 46 million years ago and disappeared in the sandstones and claystones of San Diego County’s Friars Formation. Scientists have been unearthing primate skeletons in this geological formation since 1933, but those old bones are only now being identified. The specimens at the heart of the new study were collected in the 1980s and 90s by San Diego Museum of Natural History paleontologist Stephen Walsh, Ph.D. but only now have been identified as newly discovered species.

“This research personally fascinates me because today there are no primates that naturally live in the United States and Canada,” Atwater explains to Inverse. “The fact that around 45 million years ago there were small early primates hopping around North America is very exciting to me, as well as how these early primates relate to living today.”

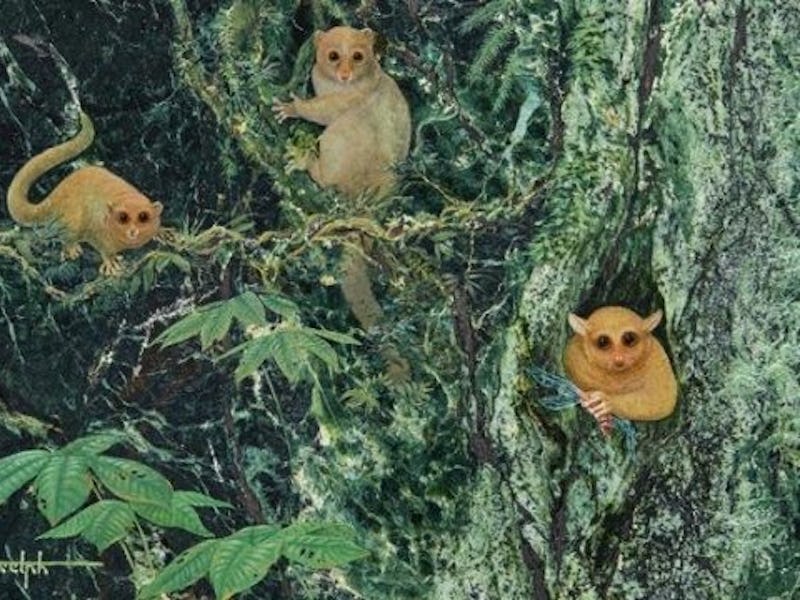

These very tiny primates, which range in size from 113 to 796 grams, are named Ekwiiyemakius walshi (after Walsh) Gunneltarsius randalli, and Brontomomys cerutt. Atwater and Kirk concluded these were unidentified species by examining their teeth and comparing them to other living and fossilized primate samples. Ekwiiyemakius walshi was comparable in size to a modern bushbaby, while the other two were closer to lemurs in size.

The *Ekwiiyemakus walshi* weighed between 113 to 125, similar to the living bushbaby seen above.

The scientists identified these animals as omomyid primates and their discovery moves up the total number of known omomyid primates from the middle Eocene from 15 to 18. While some scientists are divided on the subject, Kirk and Atwater believe omomyoids are probably the earliest known fossil representatives of the Haplorhini — a primate suborder group that includes living tarsiers, monkeys, apes, and humans.

“Omomyoid adaptive diversity is breathtaking and the group can therefore offer key insights into how independent adaptive radiations of primates have occurred in the past,” explains Kirk to Inverse. “Furthermore, since humans are also haplorhines, the evolutionary history of omomyoids should be of interest to anyone who wants to learn about the earliest stages of human evolution.”

When we think of primates, we usually think of the chimps and gorillas we see today, but primates of all other varieties have spread throughout Earth for the last 60 million years. Today there are about 350 species of living primates, but there used to be far more. Kirk says that we should anticipate “many more species of fossil primates” to be discovered in the years to come, and he’s working to describe several new species right now.

“Given their broad geographic distribution and the long period of time over which primates have been evolving, it’s pretty much a given that many more species of primates have existed in the past than are alive today,” says Kirk.

San Diego County used to be covered in a lush forest.

These omomyoids and other Eocene primates likely went extinct because of a change in climate and a loss of habitat, which are factors that threaten live primates today. While the beginning of the Eocene was very warm, a cooling trend spread across the planet about 34 million years ago. This rapidly expanded the polar ice sheets and caused the lush forests that the primates called home to disappear.

Currently, climate change affects primate environments in all regions where primates make their homes. These effects are demonstrably real, but it is difficult for scientists to predict how these changes can be mitigated and primates protected.

“Almost all primates today are threatened by extinction,” says Atwater. “We have a fossil record of primates going extinct in North America about 34 million years ago, and I wanted to understand the factors that lead to the extinction of Eocene primates to better inform conservation efforts for primates alive today.”