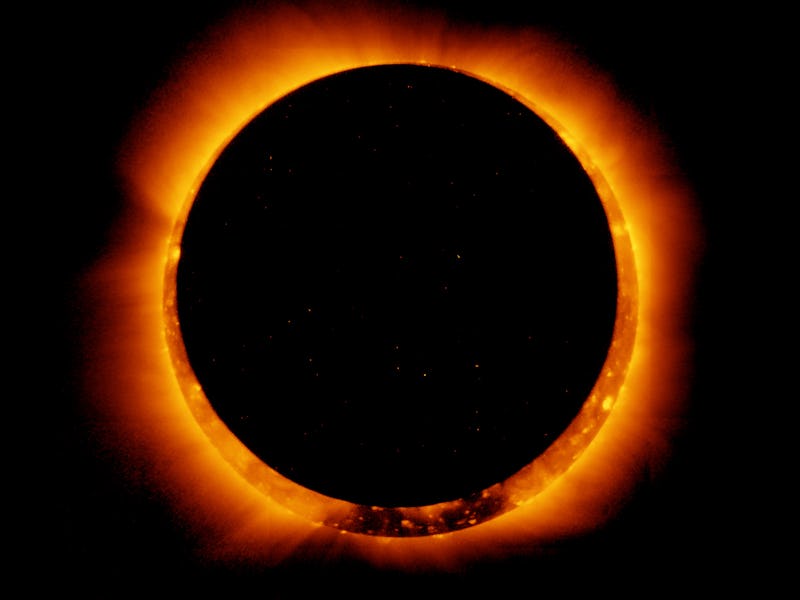

Last year’s solar eclipse stunned millions as it passed over the contiguous United States, but the space-bound spectacle was more than just a pretty light show that freaked out the pets. NASA’s chief scientist explained on Tuesday how the agency used the unique conditions during the eclipse to conduct critical experiments for Mars trips.

A quick refresher: A solar eclipse occurs when the moon passes between the sun and Earth, blocking the light and causing a shadow. Jim Green, who appeared on NASA TV to commemorate the one-year anniversary of the eclipse, explained how the agency started planning three years beforehand to make the most of the unique conditions the eclipse would produce. Most notably, it was expected to create conditions that resembled Mars in part of the Earth’s atmosphere, which would allow them to test the viability of certain life forms. The August 2017 eclipse was the first in 99 years to cross the US, meaning it was a golden opportunity for the agency to use the whole country as “our entire playground.”

NASA's contraption that flew to 120,000 feet contained microbes, pictured with the eight dots on a black card.

See more: Here’s How the Eclipse Looked from the ISS

NASA released 50 balloons as part of their research plan. These latex balloons floated to around 120,000 feet, stayed there for one or two hours, and then expanded and popped. During the eclipse, conditions at that altitude roughly simulated the temperature and pressure of Mars, enabling the team to consider how microbes planted on the balloons would act during future missions — ideal for Lockheed Martin’s Mars-bound “RV in Space” or SpaceX’s manned BFR mission.

The team studied a notably resilient microbe, regularly found in scientific clean rooms, that measures just 1.81 micrometers by 1.64 micrometers. As Green explained, “we want to know our spacecraft will land and return clean.” The team placed business card-sized sample holders on 30 of the balloons, with the sample placed on one of eight white dots, along with a control held on Earth. Students launched the balloons and used GPS to retrieve the attached gondolas after they popped and returned to the ground.

Unfortunately, it’s going to be a while before the results come through. Describing microbiology as a “tough science,” Green estimates the team will have results to share by the end of the year.

Just in time for the first BFR test flights.