Discovery of Missing Stern From WWII Destroyer Reveals a Forgotten US Grave

"The entire Aleutian Campaign has been a forgotten battlefield of WWII."

Seventy-one American servicemen disappeared into Alaska’s frigid waters when the USS Abner Read hit a Japanese mine on August 18, 1943. For nearly 75 years, their final resting place remained unknown. The Aleutian Campaign, fought in the remote, fog-cloaked waters of the Bering Sea, is not often mentioned in popular accounts of World War II. But the recent discovery of the Abner Read’s stern off the coast of a remote island in the Aleutians puts the campaign back into the spotlight, bringing one of its unsolved mysteries to a long-awaited close.

The thing about the Abner Read is that it didn’t sink — at least not on that cold night in 1943. When it struck the mine, a 75-foot portion of its stern was blown straight off, killing 71, but the surviving members of the ship’s crew managed to keep the hull watertight. Eventually, the ship was salvaged, says study co-author and University of Delaware School of Marine Science and Policy director Mark Moline, Ph.D.. “After the Abner Read hit the mine and lost the back end of the ship, it was towed to port and repaired,” he tells Inverse.

“History usually highlights the loss of the ship itself and not necessarily the loss and damage of the stern from the mine.”

The Abner Read journeyed on to fight many more battles in the war, but its stern and fallen crew remained frozen in time.

“History usually highlights the loss of the ship itself and not necessarily the loss and damage of the stern from the mine.”

Onboard the research ship Norseman II, Moline and a team from the University of Delaware and the University of California San Diego hunted for evidence of the Abner Read — a site he says was “high on our list” — guided by declassified historical documents. He is the co-founder of Project Recover, a partially NOAA-funded endeavor that uses modern marine technology and historical documents to locate the underwater sites where American soldiers died during and after WWII.

The documents showed that there had been a lot of action during the Aleutian campaign around Kiska, a remote island southwest of Alaska. Part of Alaska’s Rat Island archipelago, Kiska is a long way from the mainland, about 1,368 miles from Anchorage. The waters there are deep, vast, and unexplored.

“The land areas of Kiska Island had been well documented from a historical and archeological perspective, but the underwater portion had not,” he says.

Kiska Island

The crew onboard the Norseman II set sail toward Kiska from the city of Adak, Alaska in July, becoming the first team to conduct a full investigation of the waters around the abandoned island. “The entire Aleutian Campaign has been a forgotten battlefield of WWII despite the fact that it was the only time that a foreign power occupied US territory for 200 years,” says Moline.

Currently, Kiska has a population of zero, but during WWII, it was manned by a group of ten Americans who, with their dog, constituted the US Navy Weather detachment. Japanese forces captured them and the island in June 1942, marking the moment that US territory officially became occupied by enemy forces.

That winter and spring, American bombs rained down on the island in attempts to set it free. Finally, on August 15, 1943, an Allied invasion force landed there, only to find that the Japanese forces had already secretly fled. But the threat was not over, as the mine that maimed the Abner Read three days later illustrated. Kiska’s freedom had come with grave costs.

“This was one of the major events that led to the loss of a number of US servicemen,” says Moline, explaining how his team decided to search in that area.

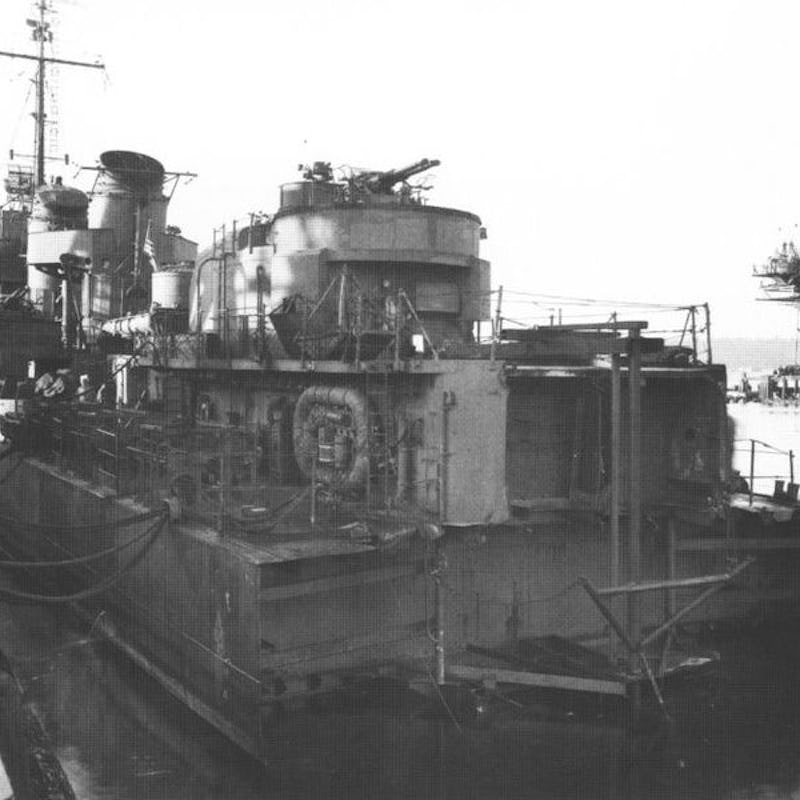

The Abner Read in June 1943.

The team first glimpsed the stern through the eyes of a remotely operated vehicle they lowered into the water. They had settled on a location after maneuvering, “lawnmower-style,” through square regions of the sea, using the Norseman II’s multibeam sonar to detect a potential target.

Because the sea off the coast of Kiska was too deep for the ship to anchor, the captain of the Norseman II had to hold station amid the blustery wind and waves while the ROV dove downward.

Multibeam sonar image of the stern section of the USS Abner Read.

The ROV’s camera showed that, over the past 74 years, the destroyer’s stern had become encrusted with vibrant gardens of branching corals and obscured by schools of brightly colored fish. But the ship’s old logbooks and reports made it clear the team had found what they were looking for.

“There was no doubt,” said expedition leader Eric Terrill, Ph.D. an oceanographer at Scripps Institution of Oceanography and Project Recover co-founder. “We could clearly see the broken stern, the gun and rudder control, all consistent with the historical documents.”

It was an emotional moment for the crew. “Needless to say, it was a humbling experience for all onboard as the ROV glided alongside and above the wreck site, clearly imaging the broken stern section, stern gun, and rudder control of this watery gravesite for the Sailors who had been lost for close to 75 years,” Terrill wrote in a blog post.

The wreckage of the Abner Read.

The researchers onboard the Norseman II have no plans to move the stern or alter the site in any way. American military wreckage is protected against removal or damage by the Sunken Military Craft Act of 2004, and besides, collecting historical artifacts isn’t the point of Project Recovery. Moline and his team do what they do to honor the past.

Wrecks like Abner Read are protected from activities that disturb, remove, or damage them or their contents by the Sunken Military Craft Act of 2004, though exceptions can be made for activities that have archaeological, historical or educational purposes. The twisted metal and sharp edges of sunken military wreckage can pose life-threatening risks to divers, but according to the Naval History and Heritage Command, there’s a more important reason to protect sites like the Abner Read. They are often war graves, recognized by the U.S. Navy as the fit and final resting place for those who perished at sea.

We thought it was not only important to document for history, but to share with the public for recognition of their service and the service and sacrifice made during the Aleutian Campaign in general.

To bring their mission to an end, the team held a memorial ceremony on the Norseman II, playing “Taps” while placing a wreath of remembrance on the site and folding a US flag in honor of the 71 servicemen who were lost in 1943.

“This finding confirms the historical accounting of this loss,” says Moline. But perhaps more importantly, it also “possibly provides some closure for the families of the lost servicemen who likely until now have not known the full story.”