"Sarawak Law": Follow Alfred Russel Wallace's Footsteps to Borneo's Jungle

Before the father of evolution, there was Alfred Russel Wallace.

The chirping of cicadas is deafening, my clothes are sticky and heavy with heat and sweat, my right hand is swollen from ant bites, I am panting, almost passing out from exhaustion — and I have a big grin on my face. At last I’ve reached my goal, Rajah Brooke’s cottage, at the top of Bukit Peninjau, a hill in the middle of Borneo’s jungle.

This is where, in February 1855, naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace wrote his hugely influential “Sarawak Law” paper. It’s as crucial to Wallace’s own thinking in disentangling the mechanisms of evolution as the Galàpagos Islands famously were to his contemporary, Charles Darwin.

Three years later, in 1858, two papers that would change our understanding of our place in the natural world were read before the Linnean Society of London. Their authors: Charles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace. In another year, Charles Darwin would publish “The Origin of Species by means of Natural Selection,” squarely positioning him as the father of evolution. Whether Darwin or Wallace should justly be credited for the discovery of the mechanisms of evolution has stirred controversy pretty much ever since.

Comparatively little has been written about Wallace’s seminal work, published four years earlier. In what’s commonly known as his “Sarawak Law” paper, Wallace pondered the unique distribution of related species, which he could only explain by means of gradual changes. This insight would ultimately mature into a fully formed theory of evolution by natural selection — the same theory Charles Darwin arrived at independently years before, but had not yet published.

I am an evolutionary biologist who has always been fascinated by the mechanisms of evolution as well as the history of my own field, and it’s like visiting hallowed ground for me to trace Wallace’s footsteps through the jungle where he puzzled through the mechanics of how evolution works.

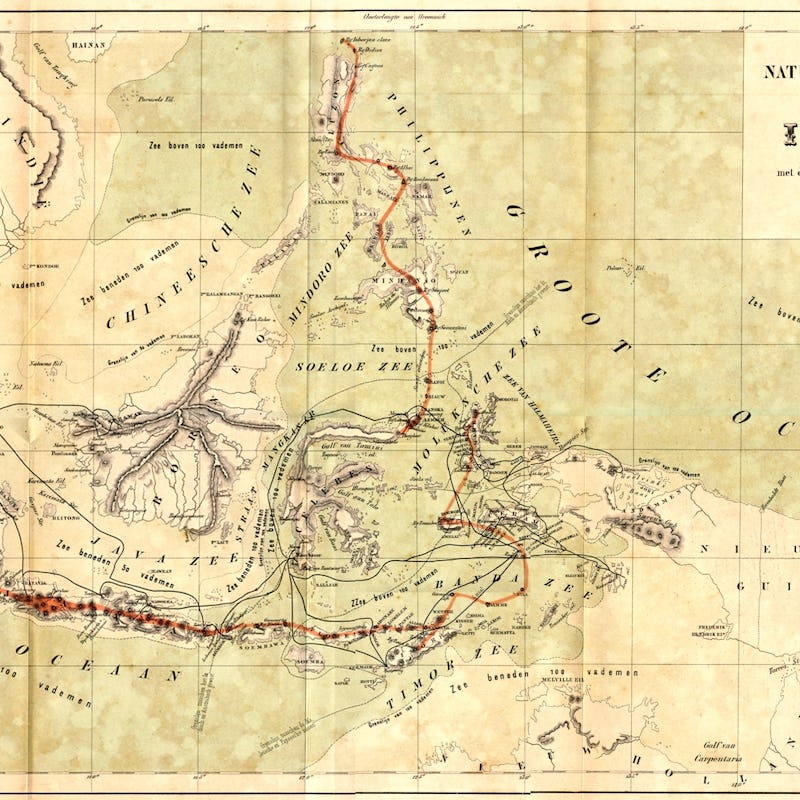

An 1874 map of the Malay Archipelago, tracing Wallace’s travels.

Forgotten Founder of Evolutionary Theory

Alfred Russel Wallace, originally a land surveyor from a modest background, was a naturalist at heart and an adventurer. He left England to collect biological specimens in South America to finance his quest: to understand the great laws that shape life. But his trip back home was marred by terrible weather resulting in his ship sinking, all specimens being lost and a near-death experience for Wallace himself.

In order to make back the money he’d lost in the shipwreck, he headed to the Malay Archipelago, a region to which few Europeans had ever ventured. Wallace spent time in Singapore, Indonesia, Borneo, and the Moluccas.

Portrait of Alfred Russel Wallace taken in Singapore in 1862.

There he wrote a succinct, yet brilliant, paper, which he sent to Charles Darwin. In it, he described how organisms produce more offspring than necessary, and natural selection only favors the most fit. The ideas he’d arrived at on his own were revolutionary — and closely mirrored what Darwin had been mulling over himself.

Receiving Wallace’s paper — and realizing that he might be scientifically “scooped” by this unknown naturalist — prompted Darwin to rush his own writings, resulting in the presentation to the Linnean Society in 1858. Wallace’s paper, now known as the “Ternate paper,” was an elaboration of his thinking, based on an earlier, first foray into the realm of evolutionary biology.

A few years earlier, when in Singapore, Wallace had met James Brooke, a British adventurer, who through incredible circumstances became the rajah of Sarawak, a large state on the island of Borneo. James Brooke would create a dynasty of Sarawak rulers, known as the white rajahs.

Upon their encounter, Brooke and Wallace became friends. Wallace fell in love with Sarawak and realized that it was a perfect collecting ground, mostly for insects, but also for the much sought after orangutans. He stayed in the area a total of 14 months, his longest stay anywhere in the archipelago. Toward the end of his sojourn, Wallace was invited by Brooke to visit his cottage, a place up on the Bukit Peninjau that was pleasantly cool, surrounded by a lush and promising forest.

Wallace described it in his own words:

“This is a very steep pyramidal mountain of crystalline basaltic rock, about a thousand feet high, and covered with luxuriant forest. There are three Dyak villages upon it, and on a little platform near the summit is the rude wooden lodge where the English Rajah was accustomed to go for relaxation and cool fresh air…. The road up the mountain is a succession of ladders on the face of precipices, bamboo bridges over gullies and chasms, and slippery paths over rocks and tree-trunks and huge boulders as big as houses.”

The jungle surrounding the cottage was full of collecting possibilities — it was particularly good for moths. Wallace would sit in the cottage’s main room with the lights on at night, working, sometimes furiously fast, at pinning hundreds of specimens. In just three evening sessions, Wallace would write his “Sarawak Law” paper in this remote setting.

Whether consciously or not, Wallace was laying the foundation for understanding the processes of evolution. Working things through in this out-of-the-way cottage, he started to synthesize a new evolutionary theory that he’d fully develop in his Ternate paper.

The birdwing butterfly Trogonoptera brookiana was named by Wallace for Sir James Brooke, the rajah of Sarawak.

Following in Wallace’s Sarawak Footsteps

I’ve been teaching evolution to college students for over two decades and have always been fascinated by the story of the “Sarawak Law” paper. On a recent trip to Borneo, I decided to try to retrace Wallace’s steps up to the cottage to see for myself where this pioneering paper was written.

Tracking down information about the exact location of Bukit Peninjau turned out to be a challenge in itself, but after a few mistakes and contradictory directions obtained from local villagers, my 16-year-old son Alessio and I found the trailhead.

The moment we started, it was obvious we had ventured off the beaten path. The trail is narrow, steep, slippery, and at times, barely recognizable as a path. The very steep incline, combined with the heat and humidity, make it difficult to negotiate.

The author with an Amorphophallus flower.

While much has disappeared since Wallace’s time, a huge diversity of lifeforms is still visible. In the thick of the jungle along the lower part of the trail, we spotted several stands of the tallest flower in the world, the aptly named Amorphophallus. Hundreds of butterflies were everywhere, along with other peculiar arthropods including giant ants and giant pill millipedes.

In some stretches, the trail is so steep that we had to rely on the knotted ropes that have been installed to help with the climb. Apparently, red ants love those ropes as well — and our grasping hands just as much.

The author on the former site of the Brooke cottage. Locals sprayed the area with weed-killer to reclaim the clearing from the jungle.

Eventually, after about an hour and a half of climbing and struggling, we reached a somewhat flat portion of the trail, not more than 30 feet long. On the right, a small path led up to a clearing, the former site of the cottage. It’s hard not to imagine Alfred Russel Wallace, thousands of miles from home, in complete scientific isolation, pondering the meaning of biological diversity. I was at a loss for words, though my teenage son was puzzled by the emotional meaning of the moment for me.

I walked around the cleared space where the cottage used to be, imagining the rooms, the jars, the nets, the moths and the notebooks. It’s an incredible feeling to share that space.

We walked down a slope to the huge overhanging rock where Brooke and Wallace found “refreshing baths and delicious drinking water.” The pools are gone now, filled in with natural debris, but the cave is still a welcome shelter from the sun.

The author in the spot where Wallace described ‘a cool spring under an overhanging rock just below the cottage.

We decided to climb to the top of the hill. Thirty minutes and buckets of sweat later, we arrived at a viewpoint where we could take in a view of the entire valley, unobstructed by the jungle. We saw oil palm farms, houses and roads. But my focus was on the river in the distance, used by Wallace to reach this place. I imagined what the primary forest, full of orangutans, birdwing butterflies, and hornbills, must have looked like 160 years ago.

In the midst of this gorgeous but very harsh environment, Wallace was able to keep a clear head, think deeply about what it all meant, put it down on paper and send it to the most prominent biologist of the time, Charles Darwin.

Like many other evolution aficionados, I’ve visited the Galàpagos Islands and retraced Darwin’s footsteps. But it’s in this remote jungle, far from anyone and anything — perhaps because of the physical difficulties of reaching Rajah Brooke’s cottage combined with the raw beauty of the surroundings — that I felt a deeper connection with that long-ago time, when evolution was discovered.

This article was originally published on The Conversation by Giacomo Bernardi. Read the original article here.