Cell Phone Use and Blindness Linked by "Toxic" Oxygen in New Study

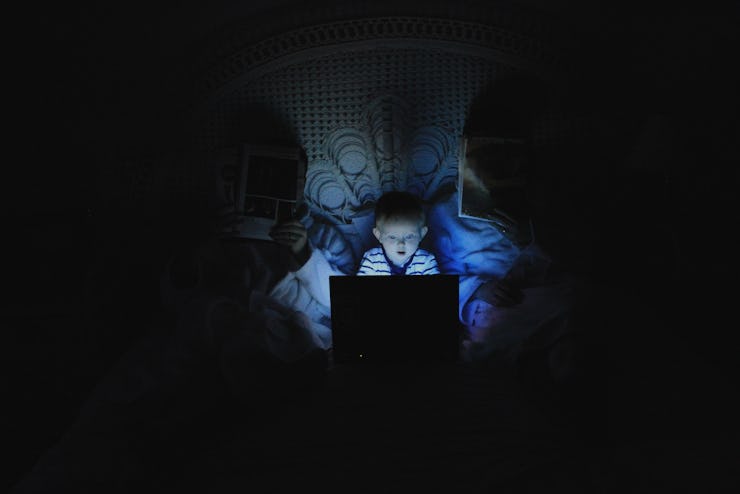

We're spending more time in front of screens than ever.

Scientists have found the chemical reason that blue lights are bad for our eyes. We know that blue light from phones, computers, tablets, and TVs mess with our sleep patterns, but it turns out they could also contribute to age-related macular degeneration, the most common cause of blindness in the United States. Unlike our ancestors, who most likely woke up with the sunrise and went to sleep with the sunset, LEDs and LCDs mean we don’t have to live like that. Unfortunately, the same technologies that enable us to live nighttime lives could also be contributing to long-term health problems.

In a paper published Tuesday in the journal Scientific Reports, a team of researchers outlined evidence that shows how blue light can cause long-term damage to our eyes. Researchers from The University of Toledo in Ohio show that when an essential chemical in the eye called retinal is exposed to blue light, it creates reactive oxygen species (ROS), free radicals that damage the photoreceptor cells in the eyes over time. The researchers say this process, which is induced by blue light from the sun as well from electronic screens, can contribute to macular degeneration.

The glow of a computer screen might mess up more than just your sleep schedule.

“Retinal is the light-harvesting antenna of photoreceptors in pretty much any animal, including humans,” Ajith Karunarathne, Ph.D., an assistant professor from UT’s Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry and the study’s corresponding author, tells Inverse. “That’s how a photoreceptor knows that light has hit it.”

In other words, the photoreceptor cells in the retina need retinal to translate light into visual information. For this reason, there’s a constant supply of the molecule in the eye. But unfortunately, when retinal is exposed to blue light, it produces toxic molecules that can permanently damage the photoreceptor cells, cells that can’t be regenerated. Karunarathne explains that the retinal absorbs the energy from blue light and transfers it to oxygen, which is abundant in the eye. This creates the various ROS that can damage photoreceptors.

“We are being exposed to blue light continuously, and the eye’s cornea and lens cannot block or reflect it,” Karunarathne said in a statement. “It’s no secret that blue light harms our vision by damaging the eye’s retina. Our experiments explain how this happens, and we hope this leads to therapies that slow macular degeneration, such as a new kind of eye drop.”

To reach this conclusion, Karunarathne and his colleagues treated some cells with retinal, exposed some to blue light, and exposed some cells to both retinal and blue light. “If you have retinal alone and keep cells in the dark nothing happens, or if you expose cells to blue light without retinal, nothing happens,” he says. But the combination of the two caused damage to photoreceptor cells as well as other body cells including cancer cells and nerve cells.

“These results indicate that prolonged exposure of cells to [blue light excited]-retinal leads to cell death,” write Karunarathne and his co-authors in the paper. “These findings suggest that retinal exerts light sensitivity to both photoreceptor and non-photoreceptor cells, and intercepts crucial signaling events, altering the cellular fate.”

One possible intervention for damage cause by blue light are these super cool Guy Fieri glasses.

For better or for worse, the cell death caused by blue light excited-retinal doesn’t usually happen until a person is about 50 or 60 years old, which is when age-related macular degeneration usually sets in. But there may be ways to protect your vision if you have to use screens, like using red-shifting features or protecting your eyes with blue light-filtering sunglasses.

Karunarathne says his lab’s next steps will be to explore which molecules can protect against the damage caused by blue light excited-retinal.

“We are trying to screen a library of molecules to see if we can identify any molecules that will reduce toxicity,” he says. The study identified a vitamin E derivative molecule that could protect against the ROS damage, so it’s possible that there are others too.

With people’s screen time rapidly increasing to over 10 hours a day on average, it’s possible that the effects of blue light excitement on retinal could be seen in younger people over time. But now at least we know how it works. The next step for researchers will be to find a way to protect against the consequences of our lifestyle.

In the meantime, Karunarathne recommends at least turning on a light if you’re using your phone at night. That way your pupils won’t be quite so dilated, and you can protect yourself from some of the blue light getting in.

This story has been updated to include further comments from Ajith Karunarathne.