Boy Who Grew Up Missing a Chunk of His Brain Shows Incredible Plasticity

"This is very interesting."

The strange case of a young boy who had a large section of his brain removed shows just how good the human brain is at repairing itself — or at least making the most of a tough situation. Beyond being just a lump of tissue that named itself, the brain is also a kind of wonderful, wet computer that’s capable of rewiring itself in response to new experiences, like taking drugs, forming new memories, and making friends. In extreme cases, like that of a 6-year-old boy who had about one-sixth of his brain removed, the brain can even adapt to getting cut apart.

Doctors documented the boy’s case in a paper published July 31 in the journal Cell Reports. They report that despite the boy having a significant portion of his brain removed, including the portion associated with visual processing, the boy has developed into a healthy 10-year-old. And while he still can’t see in the left side of his field of vision, his brain has reconfigured some of the lost connections so that he is able to recognize people’s faces. All in all, the doctors see it as a successful procedure, as well as evidence of the brain’s plasticity — its ability to adapt — when it comes to higher-order functions.

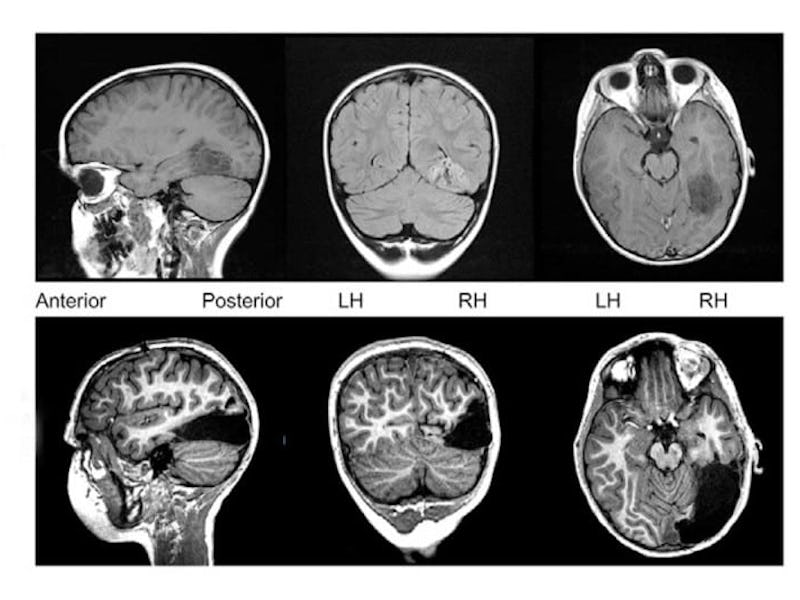

This image shows just how much of the boy's right hemisphere was removed. The black dotted lines show where there used to be brain matter.

“He is essentially blind to information on the left side of the world. Anything to the left of his nose is not transmitted to his brain, because the occipital lobe in his right hemisphere is missing and cannot receive this information,” Marlene Behrmann, Ph.D., a professor of psychology at Carnegie Mellon University and the corresponding author on the paper, tells New Scientist.

In the case study, doctors explain how, starting at age 4, the boy suffered from debilitating epileptic seizures. They soon discovered that the culprit was a slow-growing tumor in his occipital and temporal lobes in the right hemisphere of his brain, but he didn’t respond to any treatments to relieve him of his seizures. So nine months after his sixth birthday, doctors removed one-third of the right hemisphere of his brain, including some of his temporal lobe and his entire occipital lobe. While the occipital lobe is charged with visual processing, the temporal lobe also handles some degree of processing visual and auditory information, including, notably, facial recognition.

And even though the boy’s brain has not and likely will not recover the ability to process visual information taken in by his left eye, a “lower-order” task, doctors found that the left hemisphere took over some of the higher-order tasks lost in the lobectomy, including facial processing.

“His visual behavior is excellent, absolutely normal,” Behrmann tells Gizmodo. “Even though he only has one visual system, it’s been reconfigured to do the work of both hemispheres.”

The fact that they followed the boy for three years after the surgery helped them get a sense of just how well his brain adapted to the changes. They observed that his left hemisphere, which doesn’t usually handle visual processing in the way that the right hemisphere does, adapted to a region that usually processes words.

“We saw a kind of jostling in the left hemisphere between regions engaged in word and face recognition, which resolved and settled into a new organization,” Behrmann tells New Scientist.

Onder Albayram, Ph.D., a research fellow at Harvard Medical School who was not involved in the study but has done research on how cannabis induces plasticity changes in old mice, tells Inverse that the boy’s brain shows a remarkable ability to reorganize, one that may have been with us through our evolutionary history.

“This may be an evolutionarily conserved mechanism of how the brain evolved,” he says. “This is very interesting.”