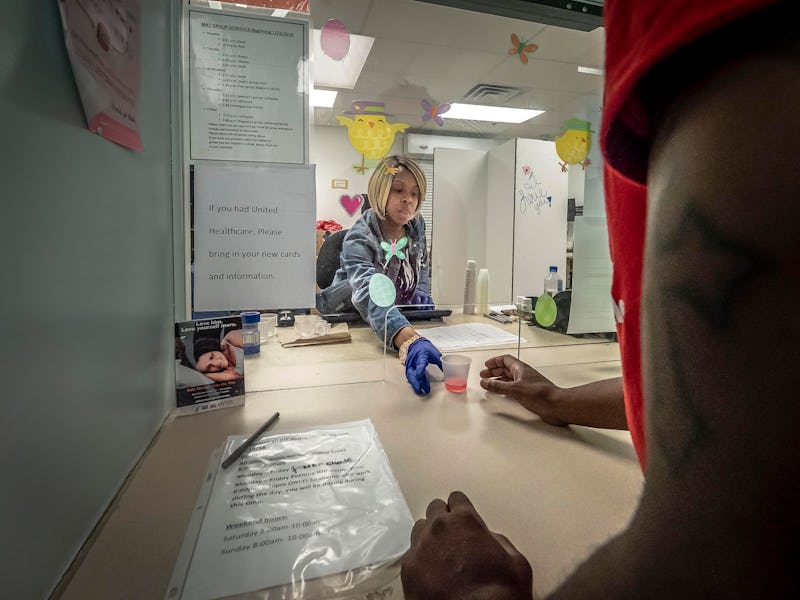

Methadone Helps Give Opioid Dependent Ex-Offenders a Second Chance at Life

"Recovery from addiction is something that everybody should expect."

Methadone, an old-school treatment for opioid dependency, may get new life as researchers examine its potential for helping ex-offenders get back on their feet. The opioid crisis continues to worsen in the United States, with overdoses rising steadily and illicit opioids like fentanyl pouring in from overseas. And though the situation isn’t quite as bad in Canada, public health researchers there are still deeply concerned. While some doctors are focusing on creative solutions, a team in Canada has highlighted that methadone, which has been around for about eight decades, could still be an effective tool in the fight against opioid overdose deaths.

In a paper published Tuesday in the journal PLOS Medicine, a team of researchers at Simon Fraser University in British Columbia shows that convicted offenders were less likely to die over a 17-year period from all causes if they were prescribed methadone. The researchers found that, out of the 14,530 people whose records they tracked from 1998 to 2015, those who were on methadone were five times less likely to die from infections and three times less likely to die from an opioid overdose, as long as they were actively getting their methadone prescriptions filled. This is significant because it provides empirical support for a major point made by harm reduction advocates: that people with opioid use disorder should have greater access to medication-assisted treatment.

Initially, the researchers were motivated by investigating the connection between methadone and overdose, but they ended up finding a broader connection between methadone and all-cause mortality.

“There’s sort of a common-sense hypothesis that if people are not taking methadone then they’re very likely to be taking opiates illicitly, and so we were interested in knowing if people are receiving methadone then how consistent are they in their use of methadone,” Julian Somers, Ph.D., a professor of health sciences at Simon Fraser University and the senior author of the study, tells Inverse. “And we found, as we expected, that there was a very strong relationship between taking methadone and protection against mortality from overdose and a variety of other causes.”

And even though government policy often doesn’t always seem to be based on science, in this case, the public health research matches up nicely with public health policy. In June the National Institutes of Health announced that expanding access to medication-assisted treatment is among its top strategies for fighting the opioid crisis in the US. But that should just be the beginning. Somers says that long-term strategies for helping people who come into contact with the criminal justice system, experience homelessness, or live with substance abuse issues should include a holistic approach that recognizes the ways these different factors interact and reinforce one another. And without a broader approach, methadone is just a bandage on a bullet wound.

Fentanyl, a synthetic opioid, is increasingly showing up in heroin, leading to accidental overdoses. And so are other synthetic opioid analogs of fentanyl.

“Methadone clearly plays an important role in protecting people against death, but in order for us to get the full benefit from methadone, we need to have available other forms of support like housing, like support for the treatment of mental illness, so that we’re able to properly treat people whose needs are not limited exclusively to opiate dependence,” says Somers. “We recognize that for many many people, opiate dependence occurs alongside other crucial areas requiring support, and if we don’t support these interrelated needs, we are not even coming close to realizing the benefit of an investment like methadone or other kinds of opiate agonist treatments.”

C. Michael White, Pharm.D. the department head and professor of pharmacy practice at the University of Connecticut who was not involved in the study, says that this study provides an important look at the role of methadone in helping people with substance use disorder, and he echoes the concern that methadone can’t be an end-all solution.

“For many people, methadone maintenance doesn’t get them off of opioids,” he tells Inverse. “It just shifts the opioid they are using to methadone.” He also points out that, in an observational study like this one, it can be hard to tease out confounding factors. Nonetheless, it’s a strong start. “Given the opioid epidemic, this type of data can be very heartening because it shows that there is a way forward for opioid addicted people that can provide a longer life.”

Somers acknowledges that, though this paper shows the potential of methadone as a tool in fighting the opioid crisis, it’s just one tool, and it won’t work unless local governments help people who need a little more help. He points out that mental illness, drug addiction, homelessness, and contact with the criminal justice system are deeply intertwined, with each factor reinforcing the other, and only by addressing them all will any of them get better.

“These crises are in some ways one interrelated crisis,” Somers says. “One of the big things that I hope comes out of this is publicizing the fact that recovery from addiction is something that everybody should expect.”