What Life Could We Find in the New Martian Lake?

"We’re talking microbial life."

On Wednesday, a team of Italian scientists announced that they’d found evidence of a large reservoir of liquid water beneath the surface of Mars. If true, this finding adds to the growing body of evidence that Mars is not the cold, dead place we once thought it was. Of course, whenever scientists announce they found something on Mars, one of the first questions that comes to everyone’s minds is Does this prove there’s life on Mars? And as usual, the answer is No, not really. But this is a huge discovery, offering perhaps one of the most promising signs that Mars could be the past, current, or future home to life. And in our effort to spark curiosity about the future, Inverse is here to address just what form life on Mars might take if we were to find that it’s really there.

“We’re talking microbial life,” Paul Niles, Ph.D., a planetary geologist and analytical geochemist at NASA’s Johnson Space Center, tells Inverse. Niles wasn’t involved in this most recent discovery, but in December 2017 he co-authored a paper in which he and fellow scientists argued that the best chance to find life on Mars is below the surface. And well, this latest discovery by the Mars Express spacecraft just added a big heap of evidence to Niles’ team’s argument. But still, he emphasizes that we’re not talking about some kind of subterranean city below the surface of the red planet.

“We’re not in a position where we’re going to have anything more complex than that, I think,” he says. “Microbial life or evidence of past microbial life is what we’re looking for.”

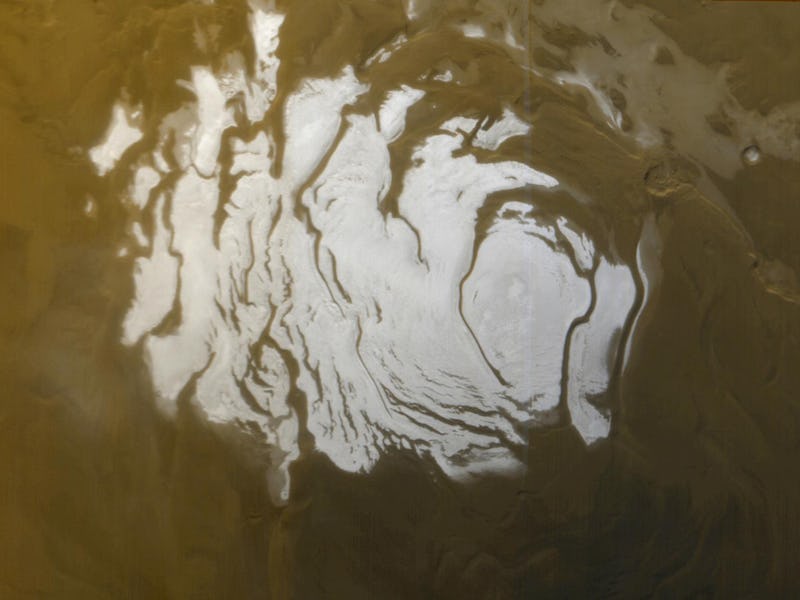

According to the team behind the new Mars findings, ground-penetrating radar shows strong evidence that there’s a large body of water almost a mile beneath the Planum Australe, a plain at Mars’ south pole. Based on previous findings of perchlorate salts in the Martian soil, it stands to reason that this water could very well be in a liquid state, since salts lower the freezing point of water.

Niles points out that whether life could survive in that water would depend greatly upon just how salty it is. And to find that out, we’d probably need to find out the temperature of the water.

“The reason temperature is important is that it can tell us how salty the water needs to be to be a liquid,” he says. “If it’s too salty the possibility of finding life is greatly reduced.” He says that it’s hard to say just how salty is too salty, but if we use Earth as any indication, our oceans approach the upper limit for salinity while still being able to support life (at least as we know it). For instance, there are microbes in salty habitats on Earth that can live at salinities much higher than those found in our oceans, but depending on what we find out about Mars’ water, it could exceed even that high level.

And while the latest Mars finding suggests the presence of saltwater, Niles says there’s a possibility that this could mean there’s freshwater elsewhere, especially if there are other subterranean reservoirs in other parts of the planet where it’s warmer — like near areas of geothermal activity.

“If you’ve got liquid water, it will flow. And if you’ve got some magma body in the crust, what can happen is the water will boil, steam will rise up into higher levels of the crust, that steam will condense and now you’ve got fresh water,” he says. “You end up with the possibility for forming a range of environments when you have warmth and liquid water present.” And not only would freshwater support a range of microbial life, it could also support human colonists on Mars in the future.

Of course, this is all highly speculative. But scientists will soon have more opportunities to explore the Martian surface, and perhaps even the subsurface, to find out how right or wrong we are: The Mars InSight lander that launched in May and the Mars 2020 rover will pick up where past missions left off. In the case of the latter rover, the landing site is still the subject of debate, and scientists will convene this fall to make their cases.

As far as Niles is concerned, previous rovers already explored the surface’s delta environments enough to conclude that Mars wasn’t home to photosynthetic life. He says the subsurface is where it’s at, and this latest discovery adds some fuel to that fire. Come fall, we’ll find out if others agree that’s where the next rover should go.