Modern Artist Angela Palmer on Sculpting From Science

The incredibly talented British artist on her inspirations and goals.

Angela Palmer’s work relies on impeccable technique, but not the exacting strokes or a painter of the controlled touch of a sculptor. Palmer has to be even more process oriented and exacting than that because her subject is, on some level, science and engineering. She recreates and improves upon the innovations of others. She stays a step ahead.

A former journalist, Palmer attended the Ruskin School of Drawing and Fine Art at Oxford University, where she studied anatomical drawing and drew corpses “just as Leonardo did centuries before.” Ultimately, she became immersed in the science of the human anatomy. Though her preoccupations have shifted over the years, she remains fundamentally interested in dissection.

Inverse spoke to Palmer about how she approaches her work, and what she’s learn

What kinds of scientific concepts are you most interested in exploring through art? How does art allow one to delve into these worlds in ways that others can’t?

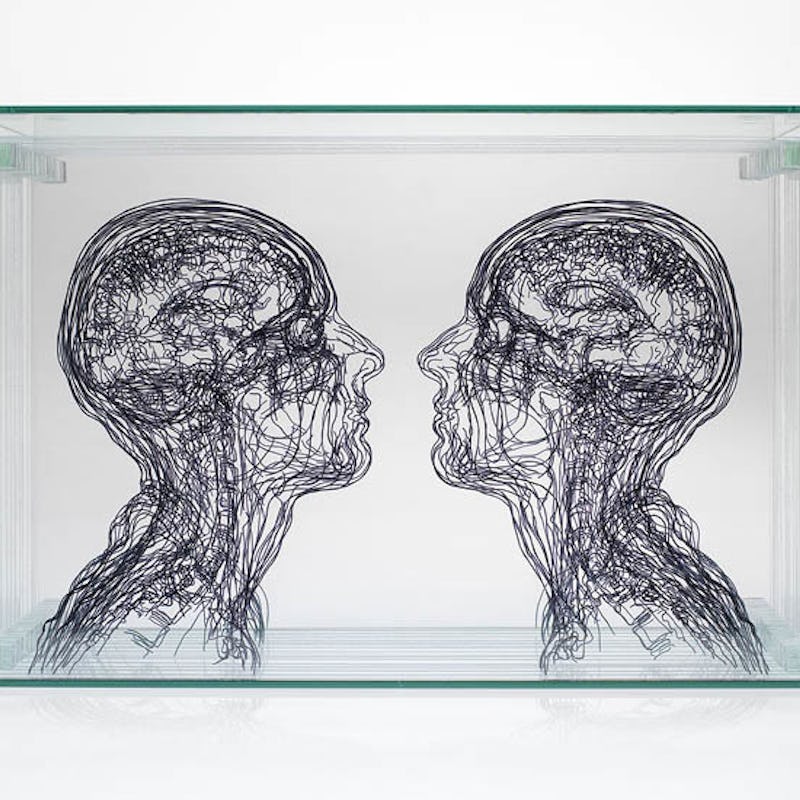

I’m interested in exploring what lies unseen below the surface and revealing the hidden architecture of not only the human form but other physical structures as well. MRI and CT scans allow me to peel back the layers and expose what is concealed below. I take details from the scans and engrave or draw the details onto multiple sheets of glass, creating a three-dimensional ‘drawing’ floating in a glass chamber.

Your website states that you have a “desire to ‘map’ at the core” or your work. Can you describe this more in depth? Do you view this drive as more an artistic pull, or a scientific one, or both?

Science allows to me to transform the scientific details contained in the MRI and CT scans into an art form so it becomes a natural and happy collision of both artistic and scientific worlds.

"Brain of the Artist," engraved on 16 sheets of glass, 35 x 30 x 14 cm

As for mapping, it is an area which has long captivated me, starting with ordnance survey maps in geography lessons at school. There’s a trigger in my brain which instantly responds to layering and mapping.

I’ve translated all manner of ‘maps’ to create three dimensional drawings, from the human form, including my own body, Egyptian mummies, cows, pigs, racehorses and an endangered green turtle to chunks of space using Nasa data, and most recently an life-size Formula 1 engine.

Through the desire to map, what have you been able to learn through the creation and completion of your works?

I’ve been introduced to a new way of seeing, and hopefully I’ve given that opportunity to others too. It has also thrown up some hitherto unknown information such as the medical condition we ascertained from the process of re-creating the Egyptian child mummy at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford. I’ve also learned that what lies below the surface, such as beneath our skin, is an architecture of extraordinary natural beauty.

How do you go about procuring access to different kinds of medical imagery and scientific artifacts?

All the work I create is a collaboration with scientists who have been incredibly generous with their time and expertise. I try to be meticulous in offering them a piece of work in recognition for providing the material. Without them the work would not exist.

Can you tell me a bit more about the work with the Ashmolean Mummy? What was that experience like — to be using modern imagery and technology to recreate a 2,000 year old mummy?

To realize the project, the child mummy was taken out of the Ashmolean in Oxford where he had lain since he was donated to the museum by the archaeologist Flinders Petrie in 1880. He was taken to be scanned by radiologists at the John Radcliffe hospital and I was given some 2,500 CT scans. I recreated him lifesize which meant I drew details of his form on 111 glass sheets in total. The project threw up fascinating details about the child — from dental and cranial evidence he was about 18 months old; he had hip dysplasia so would have walked with a limp; and an orthodontist I consulted declared the child ‘quite special’ as he was missing his baby side front teeth, a 0.04 per cent occurrence in children today. The glass ‘drawing’ now sits next to the real mummified child as a permanent exhibit in the museum, so we can show how the child looks without ever disturbing his bandages.

Part of the "Ashmolean Mummy" series

Adrenaline seemed to be a broader look at F1 that pulled these individual parts of the engine out, and presented them in a way that made the engine seem less like a convoluted piece of machinery, and more like objects that could be viewed with real aesthetic affection. Was this deliberate? Were there other goals you set out to accomplish through Adrenaline?

I wanted to apply the same to engines as I did to the human body: to peel back the layers and show what lies hidden below. Billions of us drive cars today, but few have any idea what a crankshaft or a piston looks like. I re-created the F1 engine lifesize in glass, and as a drawing floating in a chamber it takes on a totally different dimension. Again, it creates a new way of seeing.

I also took individual components of the engine and stripped them bare of their function to examine them for their sculptural qualities. I found for example the V8 exhaust fantastically anatomical, its intertwined pipes like part of the heart. I then upscaled some of the parts dramatically in different materials — for example the left exhaust is red hot orange, the colour it takes within seconds when it reaches temperatures of molten lava. It’s been an exciting project from the start, all thanks to the collaborative scientists at Renault’s F1 factory in Paris. I also wanted to capture the adrenalin and heightened sense of risk which drivers face at those dangerous speeds. To reflect this, I borrowed an F1 driver’s helmet and cast it in molten crystal. When I first saw the cast, I thought it looked like the membrane of the skull, which is precisely the vulnerability I was trying to capture.

"Red hot exhaust, Part 7," resin, 61, x 103 x 67 cm, Edition of 4

What’s next? What are you currently working on, or planning to work on?

I’m on a top secret project, and will reveal all by next October if it comes off!

You can see more of Palmer’s work at her website