Earth's Oldest Biological Color Discovered Under a Billion-Year-Old Rock

It's pleasantly bright.

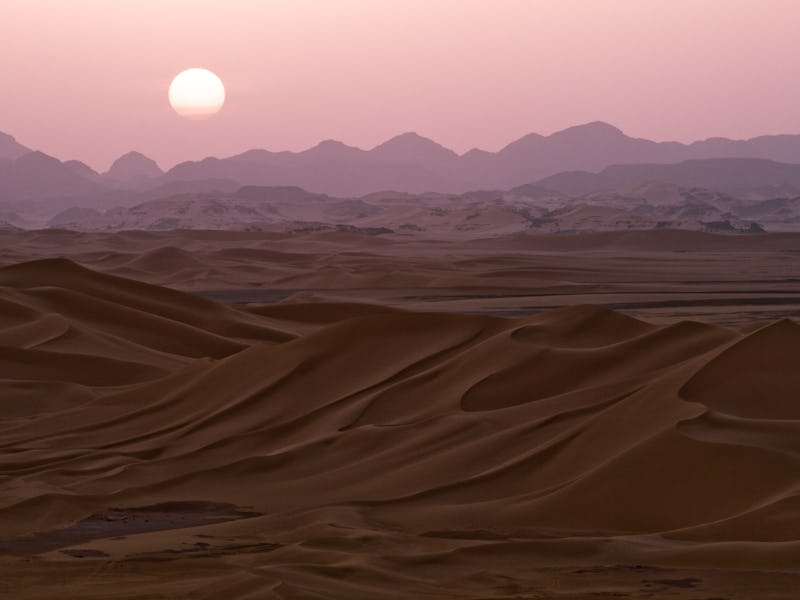

About 10 years ago, an oil company dug up a marine shale deposit in the Taoudeni basin of the Sahara Desert. When scientists at the Australian National University dated the black, sedimentary rocks, the shale was shown to be over 1.1 billion years old — a striking discovery in itself. But within the rocks, they discovered something far rarer, and shockingly bright, within the black stone: Earth’s oldest biological colors found to date.

Crushing the rocks into a powder released bright pink pigments, the remnants of ancient fossils trapped in the shale. In a study published Monday in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the team writes these colors are 600 million years older than previous pigment discoveries. ANU researcher Nur Gueneli, Ph.D., explained in an accompanying statement that these pink pigments are the “molecular fossils of chlorophyll that were produced by ancient photosynthetic organisms inhabiting an ancient ocean that has long since vanished.”

These pigmented, molecular fossils are technically known as porphyrins, a class of compounds that also include heme, which makes blood red. Co-author Amy Marilyn McKenna, Ph.D., explains to Inverse that these are “very unique molecules that have to be painstakingly assigned manually from the background oil signature, so if you are not careful, you would miss them.” At over half a billion years old, the new porphyrins, says the self-described “porphyrin junkie,” are the oldest porphyrins ever found.

A vial of pink porphyrins extracted from the 1.1 billion-year-old rocks.

The ancient pigments confirm that billions of years ago, the ocean was dominated by tiny cyanobacteria, which are characterized by the ability to obtain their energy through photosynthesis, which requires chlorophyll. While we usually associate chlorophyll with green organisms, different subtypes of chlorophyll can have different colors; the type that these ancient bacteria carried ranged from blood red to deep purple but looked hot pink when the powdered fossils were diluted.

The preeminence of cyanobacteria in the oceans helps explain why bigger animals didn’t exist a billion years ago. The emergence of large organisms, the scientists explain, is dependent on whether there is a supply of food available — and cyanobacteria didn’t make for good meals. Cyanobacteria also tended to create low-oxygen zones in the water (as they do today), which made it difficult for other forms of life to thrive.

Dr. Gueneli running the samples at the National High Magnetic Field Laboratory.

“Although the shales contained eukaryotic microfossils, a lack of detected sterane fossil molecules that would indicate eukaryotic contribution to biomass suggests that algae may have played a minimal or insignificant role in the oceans around a billion years ago,” says McKenna. “These results suggest that a lack of large primary producers in the mid-Proterozoic oceans, along with low oxygen levels, may have hampered the development of animal life.”

Algae, a much richer food source than cyanobacteria, began to spread through the oceans 650 million years ago, and the cyanobacterial oceans subsequently vanished. That allowed for life to evolve, consequently filling the planet with much more than just hot pink hues.