Ancient Skull Shows Evolutionary Link Between Humans and 'Lucy' Hominins

"It represents potentially the oldest evidence of hominin evolution in South Africa."

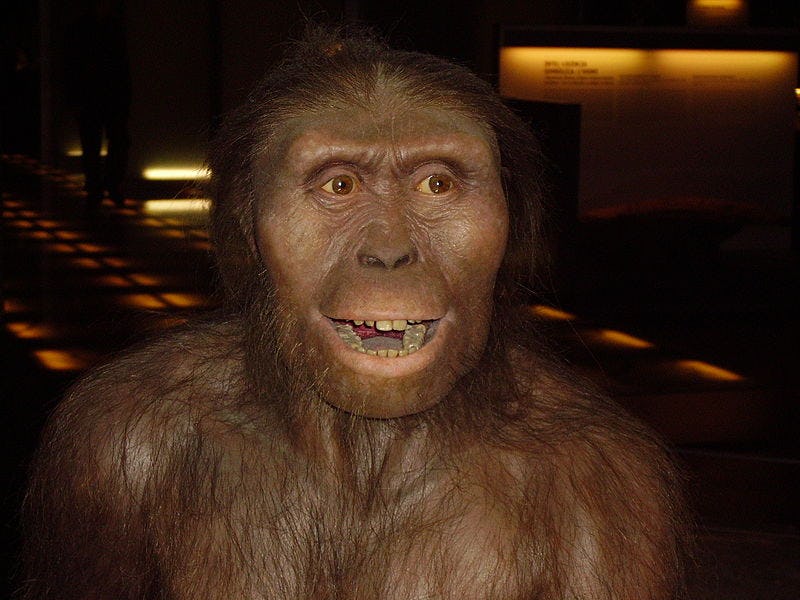

Long before Neanderthals or Homo erectus wandered the Earth, there lived an early human species called Australopithecus afarensis. Most famously represented by the specimen known as Lucy, these ancient hominins lived around 3 million years ago in Eastern Africa and survived for more than 900,000 years. Lucy looks quite different to modern humans, but a new study on the cranium of one of her kin suggests that the two species are more alike than we realized, suggesting it’s time to reconsider our evolutionary tree.

In a paper published in the May edition of the Journal of Human Evolution, a team of South African scientists re-evaluate a four-million-year old Australopithecus skull that was originally found in 1995 in the Sterkfontein Caves, a paleoanthropological treasure trove north-west of Johannesburg, South Africa. The Jacovec cranium, as it’s known, has a fragmented brain case, which made it hard for researchers to study it in the past. But with a new technology called X-ray microtomography, the team was able to take a very revealing look at the ancient skull.

Co-author and University of Witwatersrand researcher Amélie Beaudet, Ph.D. tells Inverse that “this specimen was of primary interest to us, as it represents potentially the oldest evidence of hominin evolution in South Africa.”

Original picture (left) and virtual rendering (middle) of the Jacovec cranium.

With X-ray microtomography, Beaudet and her team were able to quantify the skull’s cranial thickness and composition. Because there is little evidence of the brains of our ancestors, she says, what we know about them comes from studying internal casts of brain cases. That’s why she and her team hypothesized that the “exploration of the inner anatomy of the cranium may provide additional evidence for learning more about the cerebral condition in fossil hominins.”

Sure enough, their analysis affirmed that the specimen met the taxonomic qualifications to be an Australopithecus and, importantly, demonstrated that this ancient hominin had a cranium that was thick and composed of spongy (or cancellous) bone — much like living humans. The presence of spongy bone indicates that the blood flow in the brain of Australopithecus may have been comparable to ours.

Dr. Amelie Beaudet with the cranium.

In turn, this indicates that the brain case of the Australopithecus may have played an important part in protecting its evolving brain. Shara Bailey, Ph.D., an associate professor at New York University’s Center for the Study of Human Origins that did not work on the new study, tells Inverse that an increase in blood flow means an increase in oxygen traveling to the brain, which suggests a brain that needs more fuel.

“It seems that the increase in blood flow to the brain exceeds what would be expected for the brain of a primate our size,” Bailey says in regards to this new study. “This could be indicative of a greater number of neural connections.”

While this is an interesting discovery, Bailey says, it’s too soon to say that human-like craniums were a wide-spread trait among Australopithecus populations.

“The issue with making sweeping statements from a single individual is that we do not know what is idiosyncratic and what is ‘typical’ for that species,” says Bailey. “There are other reasons why cranial bones may be thickened, including pathological explanations.”

In an effort to gather more comparative samples, Beaudet says that her team will collect additional evidence from cranial remains, teeth, and long bones — samples they’ll need to “reconstruct the biology and evolution of our ancestors and their remains.” Over 800 hominin fossils have been gathered in the Sterkfontein Caves since 1936. Now, with the help of new technology, scientists can evaluate them in a way that results in a broader understanding of human evolution.