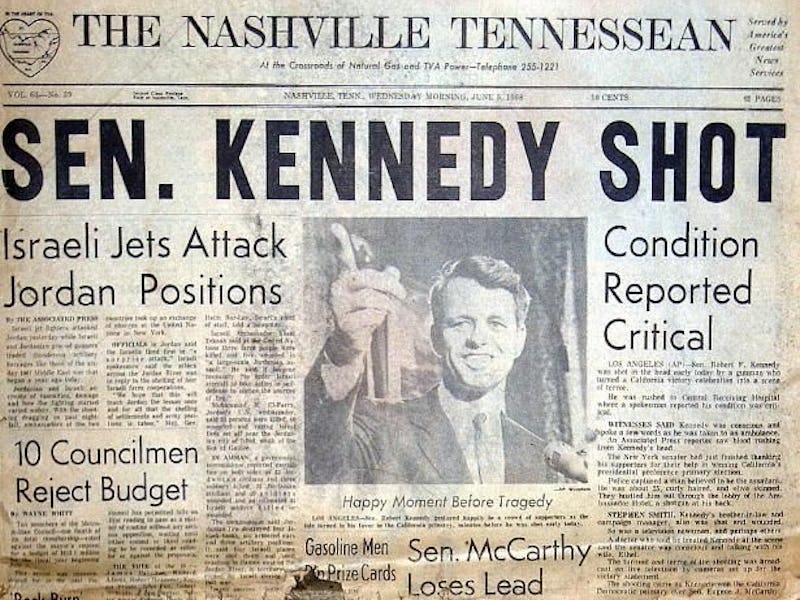

Neurosurgeons Reveal New Details About Robert F. Kennedy's Assassination

"If you could do it over, you would try to get him to the correct hospital."

On June 5 1968, democratic presidential candidate Robert F. Kennedy walked out of Embassy Ballroom in Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles. Within seconds, American politics changed irreparably as he was shot three times at point-blank range. Now, fifty years later, a team of neurosurgeons at Duke present another look at the facts of the case in the Journal of Neurosurgery. They want to know: Was there a way to save RFK?

“We write papers about assassinations or illness in famous public figures if they have never been reviewed from the medical point of view,” Dr. Theodore Pappas, a co-author of the new paper and Vice Dean for Medical Affairs at the Duke University School of Medicine, tells Inverse. “We try to find new facts that no one has heard of.” Pappas and his team of neurosurgeons at Duke have spent the past few months combing through the medical records and eyewitness accounts that survive from the day Kennedy was killed.

Their paper reads like something between a clinical review and a true crime story, reconstructing Kennedy’s emergency surgery minute by minute. This painstaking work paid off: They found that there were 45 minutes that could have been saved during Kennedy’s emergency treatment, and that although he was shot three times, only one of the bullets caused the fatal damage.

RFK delivering a speech in 1968, months before he was fatally shot

According to the publicly available medical records and the autopsy report, Kennedy hit the ground around 12:15 AM. Within minutes, his small security detail — consisting of a former NFL lineman, a Olympic decathlete, and the Los Angeles Police Department — had a choice to make: There were two hospitals within two miles of the Ambassador Hotel, the smaller Central Receiving Hospital and the larger Good Samaritan Hospital. An ambulance was dispatched to the smaller of the two, the researchers say, because of a critical miscommunication: the ambulance dispatcher didn’t know that Kennedy’s injury was a gunshot to the head.

At 12:32 AM, the senator arrived at Central Receiving Hospital, where a team tried to resuscitate him.

An artist's reconstruction of the team's data from the autopsy report.

The team’s analysis of what is known as “the perfect autopsy” because of its attention to detail showed that the fatal bullet entered Kennedy’s right cerebellum and right occipital cortex, near the back of his head. That wound scattered both bone and bullet fragments throughout the brain, severing a crucial artery. Fixing it would have required a craniometry, a surgical procedure that removes a small portion of the skull to access the brain. Unfortunately, smaller hospitals didn’t have the neurosurgery expertise on staff to treat injuries as severe as Kennedy’s, as Pappas explains.

“The fact that he was taken to a very small hospital first prior to being transferred to a hospital with neurosurgeons caused an unfortunate delay,” he says. “It’s obvious that if you could do it over you would try to get him to the correct hospital directly from the hotel where he was shot.” The team estimates that doing so would have bought back the 45 minutes that were wasted as Kennedy was transferred two blocks to the Good Samartian Hospital for surgery.

The LAPD's Rampart Station stands on the former site of Central Receiving Hospital.

However, even that amount of time may not have done much to save the senator’s life. Kennedy’s odds of survival were around 54 percent — odds that, they say, hold true for similar injuries today. They believe that RFK was given “aggressive and appropriate care in line with the standard from the day.” The important word to note here is “aggressive”: Pappas adds that most people would not have even received surgery given the nature of the injury and the fact that Kennedy never showed signs of consciousness after he left the first hospital.

“If he had not been a sitting senator, it is possible that some neurosurgeons would not have offered operation,” Pappas says.

It seems as though even modern-day tools would have done little to save Kennedy. But the fact that he received treatment at all allows for an important historical case study. The results aren’t highly technical; the findings can be boiled down to “Next time, pick the right hospital.” What it ultimately shows is the inevitability and consequences of human error, and Pappas believes that studying these moments can help us “learn about ourselves by understanding our past.”