RETRO GAME REPLAY | 'Space Harrier' (1985)

Yu Suzuki's run-and-gun is an onslaught of colors and skill.

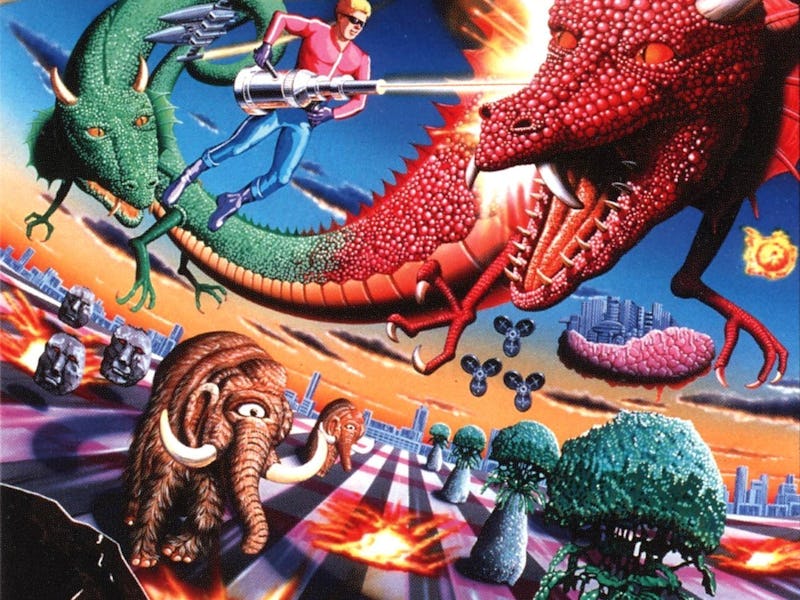

Imagine an acid trip through an ‘80s anime, a Robert Jordan novel, and early Silicon Valley binge coding sessions. That’s what Space Harrier looks like, the mid-‘80s rail shooter from Sega that set the foundation for the third-person shooter.

There’s a story to Space Harrier. It’s flimsy, presented in really weak scrolling text ala Star Wars and loaded with typos and grammatical errors, but Yu Suzuki and his team tried to have it make sense. And gosh darn did they try. Developed by Sega AM2 and released to arcades in 1985, Space Harrier portrays you as a super-rad human from Earth with “physic powers” (They meant “psychic”) as you shoot down cyclops mammoths and Chinese dragons against a virtual landscape wrecked by an evil presence threatening the “Fantasy Zone.”

And it’s pretty hard. The illusion that the game was 3D was powerful; Mr. Space Harrier (I’m guessing that’s his name) is continuously moving forward at a break-neck pace. In addition to shooting down enemies and dodging fire, you have to watch out for bushes, trees, and big-ass stones, pipes and… What kind of land is the “Fantasy Zone” really? It looks like daytime in Tron, but is it supposed to be Middle Earth too? Regardless, precise timing and a knowledgeable visual vocabulary of exactly what’s what is needed. If you’re not careful, you’ll confuse a fireball for an enemy who will fire fireballs at you anyway so just shoot the thing and keep moving.

Yu Suzuki, renowned for creating technically elegant games like OutRun and the Shenmue series, pushed the boundaries of the era’s technical limits to the fringe in Space Harrier. It was among the first to use 16-bit technology, which they used in conjunction with a signature of Sega’s, their “Super Scaler” that enabled pseudo-3D visuals at extremely high frame-rates. “Oh Suzuki, you’ve done it again,” I picture a refined, high-powered Japanese video game executive saying with a sitcom-esque tone, hands at his hips as a grinning Suzuki show off his game. Cue studio audience laugh.

Several versions of the arcade machine exists. There was the standard, standing-up model seen in every arcade ever, a static “sit-down” featuring a cock-pit and a joystick, and another one with a cock-pit and a joystick and it moves with you! I can’t imagine how that would be useful in playing, though. In fact, why sit? Your character is flying through the air, how is sitting an immersive game element?

My own encounter with Space Harrier wasn’t actually with any of those arcade cabinets, unfortunately. Mine came through Shenmue on the Sega Dreamcast.

It’s amazing how deep Shenmue from 1999 on the Sega Dreamcast actually was. It was already a huge, sprawling game, but there was still enough to fit in mini-games, one of them being Yu Suzuki’s own Space Harrier, a port from the Sega Saturn console. That’s how I first played it, not on a joystick on a cabinet like it was perhaps meant to be played, but on the very complicated and awkward to handle Sega Dreamcast pad. Still, it was Space Harrier, and it was awesome.

The legacy of Space Harrier is muted. It implemented many innovations of its day, and masterfully created 3D without actually rendering anything in 3D. 1985 saw the release of Super Mario Bros. on the NES, and it wouldn’t be for a few years until Sonic the Hedgehog on the Sega Genesis blew everyone away with such speed and gorgeously created environments.

But there was Space Harrier, running faster than the trend and shooting from the third-person before Gears of War made it great.