Sperm Study Shows What Long-Term Stress Does to Their Swimming Speed

Another tough break for sperm science.

With so much bad news regarding falling sperm counts, stressed out dads, and fertility-related health problems, the sperm of the Western world hasn’t had much to celebrate. Adding to the pile of studies documenting the woes of modern sperm, new research presented at International Summit on Assisted Reproduction and Genetics on Wednesday shows a new problem: in some stressed-out men, sperm are getting slower.

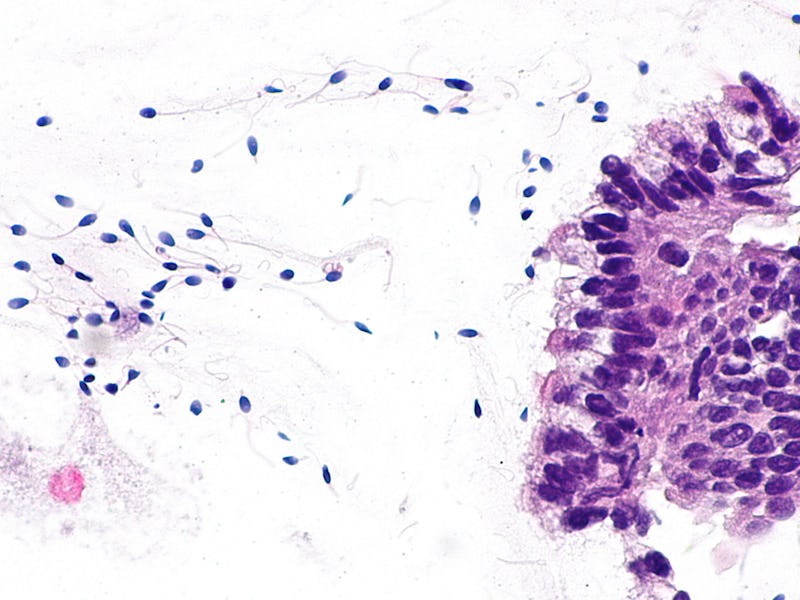

In the new study, Eliahu Levitas, Ph.D., of Israel’s Ben-Gurion University showed, using samples from people experiencing the ongoing Israel-Gaza conflict, that long-term psychological stress has a detrimental physical effect on the health of sperm. Levitas and his team collected 659 sperm samples from participants who had experienced prolonged periods of stress during the conflicts between 2012 and 2014. Of those samples, they found that 37 percent had low motility — an inability to swim — which they link to the participants’ experience of the prolonged psychological stress of constant warfare.

“Our reasoning was that even men who heard incoming rocket warning sirens during a conflict experienced stress throughout the day over a longer period,” Levitas in a press release published Wednesday.

Dr. Levitas' study found a relationship between psychological stressors of the Israel-Gaza conflict of 2012-14 and sperm motility

His research points out an important distinction in the field of sperm science: Recent studies on infertility have shown the effect of stress and environment on sperm count, but Levitas’s work reminds us that infertility can stem also from low sperm motility and, as a study in the New England Journal of Medicine called it in 2001, “abnormal morphological features.” In other words, you can have the highest sperm count in the world, but if sperm motility or physical health is low, infertility can still become an issue. Levitas’s study specifically documented the effect of psychological stress on sperm swimming speed, showing that the probability of having slow swimmers is 47 percent higher in men who are experiencing prolonged stress.

While the new study was more focused, many studies in the field of sperm science examine both motility and count as they search for an explanation. Studies have examined the damaging effect of air pollution on sperm count and quality. Another study, published in Human Reproduction Update in 2017, suggested that the persistent popularity of skinny jeans could potentially reduce sperm count.

Researchers from Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health really tried to go for the gold in their 2014 attempt to analyze all of these variables in one big sperm meta-study on 193 men. These researchers analyzed 10 categories of “life stress” and “work stress” variables,” including income-related stress, hazardous exposures, and race-related stress, to name a few.

“In this first study to examine all three domains of stress, perceived stress and stressful life events, but not work-related stress were associated with semen quality,” the researchers wrote.

The percentage of "normal sperm" versus the "perceived stress' of the Columbia study participants

The new analysis of declining sperm motility and psychological trauma was consistent with the “life stress” results of the Columbia mega-study. Levitas didn’t identify the occupation of his participants, so unless they were active military, the Israel-Gaza conflict wouldn’t qualify as “work stress.” But Columbia researchers warned that there is still a lack of consensus around the causes of the current sperm crisis.

In the meantime, researchers will just have to keep casting a wide net.