Since November 2014, scientists have used a global network of telescopes to detect tidal disruption flares, which are basically powerful explosions of X-ray radiation that occur when a black hole chows down on a star. Scientists now have a better idea of just how big the belch is compared to the bite.

A new study from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Johns Hopkins University have picked up radio waves that almost mirror the X-rays of the flare. This is evidence of a giant beam of energetic particles surging out of the black hole proportionally to how much stellar material is falling into it. Think of this as a sustained burp the black hole unleashes into the universe as it’s sipping on that star juice.

Join our private Dope Space Pics group on Facebook for more strange wonder.

“We found that the radio [waves are] actually an ‘echo’ of the X-ray light,” Dr. Dheeraj Pasham, lead author of this study, tells Inverse. “We know that the X-rays very likely come from the hot material that is falling into the black hole. The fact that we see the same emission pattern in radio roughly two weeks after is telling us that there is a clear connection with what is going into the black hole and what is emitted out.”

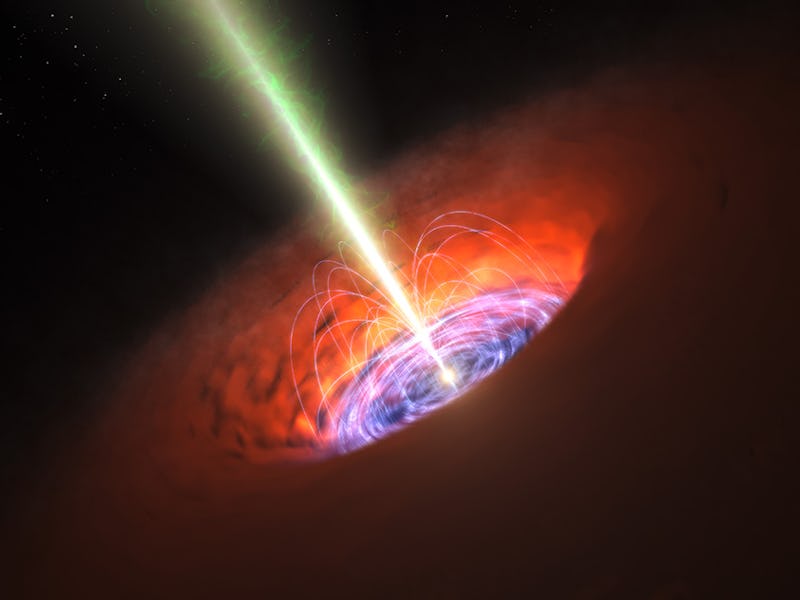

A hungry black hole eats a star. Chomp chomp chomp.

In a paper published in the The Astrophysical Journal Pasham and his colleagues provide answers to a question that has long eluded scientists.

A black hole’s gravitational forces are almost unimaginable. When a rogue star passes by one the black hole begins to stretch and flatten it until the star is completely torn to pieces, which it then completely devours.

This black hole feeding frenzy created bursts of optical, ultraviolet, and X-ray radiation that stem from insanely hot material pouring into the black hole. However, occasionally scientists would detect unexplainable radio waves.

“We know that the radio waves are coming from really energetic electrons that are moving in a magnetic field — that is a well-established process,” says Pasham in a statement. “The debate has been, where are these really energetic electrons coming from?”

Computer-simulated image of gas from a black hole shredding a star that wandered a little too close.

Pasham and his team have been able to link these once-mysterious radio waves to a jet of energy that the black holes begin to release once they’ve been munching on a star for a while. A lot how we humans belch after a good meal.

With this study under their belts, Pasham’s team can set their sights on understanding exactly what makes black holes so burpy, which could lead them to understanding even more about the universe as a whole.

“In the future events where a black hole gobbles up a passing star, we can train radio telescopes to understand how exactly black holes produce these very energetic jets some of which seem to even influence how their host galaxies evolve,” Pasham explained.

Who knew an intergalactic burp could be some informative?

Additional reporting by Rae Paoletta