Is Space Cooperation Keeping the U.S. And Russia Together?

NASA and Roscosmos have never been closer or more under threat.

The U.S. and Russia are currently at odds on almost every global issue. But the two superpowers (okay, superpower and a half) remain close allies on one non-global issue. We’re still friends in space.

This year marks the twentieth anniversary of the first joint U.S.-Russia space missions, which dispatched space shuttles to the Mir, an important precursor to the International Space Station. In February 1995, not long after the end of the Cold War, the Russian cosmonaut Vladimir Titov flew to Mir on a U.S. space shuttle in a symbolic event that served as the “dress rehearsal” for the many collaborative flights to come. With America taking a hard stance against Russia’s military activity in Ukraine and Putin’s irresponsible foreign policy generally, NASA and the Russian space agency Roscosmos continue to propose new cooperative projects. But is space collaboration the only thing keeping these countries together and will it be enough?

When Russia annexed the autonomous Ukrainian peninsula of Crimea in March of last year, the U.S. responded by imposing sanctions on Russia’s financial, energy, and defense sectors. Russia officials almost immediately pointed out how badly the sanctions could affect their space program — an ominous hint that NASA might be the next to suffer. And that’s a problem if you’re the U.S., which ended the Space Shuttle program in 2011. The only way for American astronauts to get to the ISS is to buy seats on Russia’s Soyuz spacecraft.

“We’re in a hostage situation,” former NASA administrator Michael Griffin said in an interview with ABC News. “Russia can decide that no more U.S. astronauts will launch to the International Space Station, and that’s not a position that I want our nation to be in.”

The situation seemed especially bleak when, commenting on the sanctions, the Russian Deputy Prime Minister Dmitry Rogozin tweeted the following: “After analyzing the sanctions against our space industry, I suggest to the USA to bring their astronauts to the International Space Station using a trampoline.”

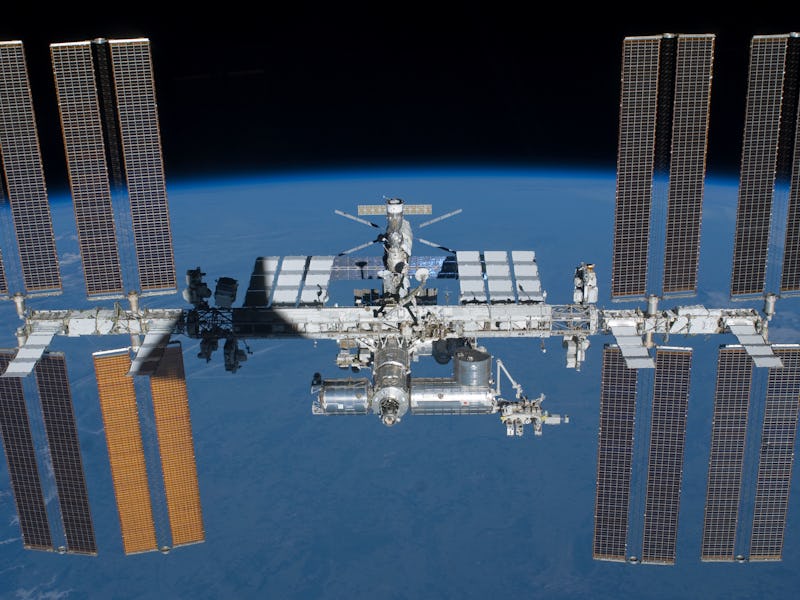

And yet, despite the ever-worsening situation between the two countries, NASA and Roscosmos have managed to continue their collaborative relationship. Even as the U.S. and Russia began one-upping each other’s sanctions last year, with NASA being forbidden from contacting the Russian government, one big exception was made: the operation of the ISS was allowed to continue. The ISS is a $100 billion project that is physically split into two sections: the Russian Orbital Segment and the US Orbital Segment. There’s a lot of interplay between the two sections — sharing power, staff, and cable connections — and so far, there haven’t been any issues surrounding their cooperation. They seem to get along just fine.

Just this past March, NASA and Roscosmos hit another important milestone in their relationship: they sent an astronaut and cosmonaut, Scott Kelly and Mikhail Kornienko, to the ISS for an unprecedented year-long mission to conduct research for future trips to Mars. “This is not Russia’s first venture into having people stay in space a year or longer,” Kelly said during a preflight news conference. “But the big difference with this flight is that it is the first time we’re doing it with an international partnership, which I think is one of the greatest success stories of the International Space Station.” And not long after Kelly and Kornienko left for the ISS, NASA and Roscosmos made another landmark announcement: They had agreed to collaborate on a future space station to replace the ISS once it’s retired in the 2020s, with the future goal of launching a mission to Mars.

In light of the ever-worsening relations between Russia and the U.S., things seem relatively rosy for NASA and Roscosmos. It’s unclear, however, how much of their relationship stability can be chalked up to sheer good will and how much is a result of financial and scientific co-dependence. It’s no secret that private companies like Boeing and Elon Musk’s SpaceX are developing spacecraft to bring American astronauts to space without Russia’s help, but until they succeed in creating one that won’t blow up, the U.S. is dependent on the Soyuz spacecraft to get their astronauts to the ISS. The U.S. relies on Russian technology for its space projects outside of the ISS, too; Atlas V rockets, for example, are powered by Russian-made engines. And Roscosmos, apparently, is a little strapped for cash, so it probably doesn’t hurt to have NASA around to buy $60 million seats on their shuttles to the ISS. Until China finds a way to cooperate in ISS missions, the U.S. and Russia are pretty much stuck with each other.

Even though their countries constantly threaten to sever the relationship between NASA and Roscosmos once and for all, those threats have — as of now — come to nothing. Only time will tell whether their shared interest in a new space station and Mars missions will be enough to keep them together as politics tries to tear them apart.