30 Years of Satellite Data Reveal Unexpectedly Bad News for the Ozone Layer

The holes at the poles are no longer our biggest concern.

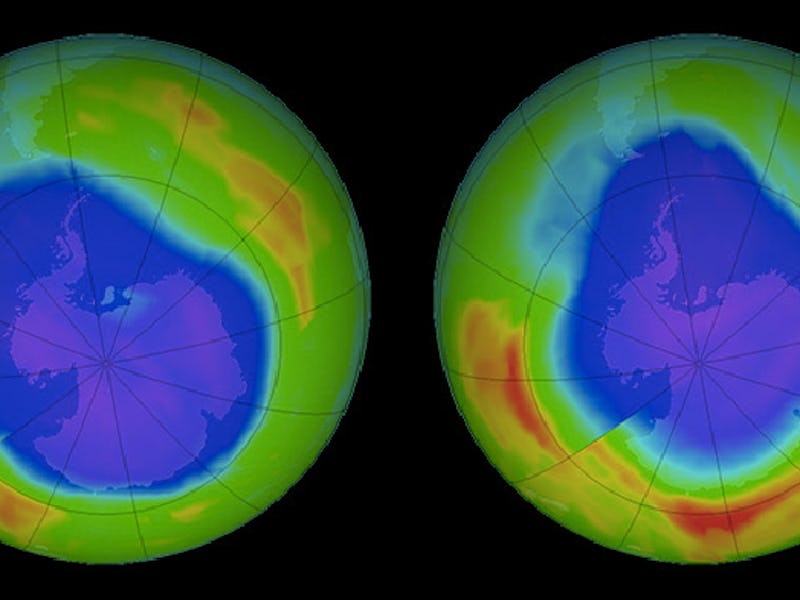

In June 2016 scientists announced that there was evidence of the “first fingerprints of healing” in the ozone layer above Earth’s poles. This was great news: We need the ozone layer to absorb UV radiation from the Sun, and holes mean that radiation can pass through and damage the DNA of plants and animals. Closing them up meant we were finally doing something right for the environment.

On Tuesday, however, an international team of researchers scaled back the excitement with a grave announcement in Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics: Despite the progress at the poles, the swath of the ozone layer at lower latitudes — a region covering London, New York City, and Buenos Aires, and many other big cities — is not recovering. This huge stretch of the globe, they write, not only covers the most highly populated regions but also gets the most intense sunshine.

It is “not a good signal for skin cancer,” study co-author and Grantham Institute for Climate Change co-director Joanna Haigh, Ph.D., told The Guardian on Tuesday.

Ozone forms in the stratosphere and we live in the troposphere.

What’s most concerning is that the Haigh and her team don’t really know why recovery is stalling at lower latitudes.

“The finding of declining low-latitude ozone is surprising since our current best atmospheric circulation models do not predict this effect,” co-author William Ball, Ph.D., said in the statement. “Very short-lived substances could be the missing factor in these models.”

The success we’ve had at closing up the ozone holes at the poles has been attributed to the Montreal Protocol, a United Nations agreement passed in 1987 ordering the phase-out of chemicals called CFCs. These chemicals, found in refrigeration systems and aerosols, drift into the stratosphere, release chlorine, and destroy ozone, a highly reactive gas. It’s not clear why these interventions have had more success at the poles than at lower latitudes.

The researchers have some theories: One thing driving the continuous decline in ozone is that climate change is altering the pattern of atmospheric circulation, shifting ozone further away from tropical latitudes. Another possibility is that very short-lived substances (VLS), chemicals that are used as solvents, paint strippers, and degreasing agents, may also be destroying the ozone in the lower stratosphere.

NASA's prediction for ozone concentration levels.

The researchers noticed the slowly recovering areas after examining satellite data collected since 1985, which allowed them to create a 30-year record of atmospheric ozone and how it’s been measured over the years. Analysis of the ozone levels between the 60th parallels — as far north as Alaska and as far south as the bottom tip of Argentina — revealed impaired ozone recovery in those regions.

This bodes poorly for us humans, said Haigh, explaining in the statement that “the potential for harm in lower latitudes may actually be worse than at the poles” because in these regions UV radiation is more intense and more people live there.

The next step for the researchers is gathering more precise data on ozone decline and determining exactly what is driving the impaired ozone recovery. They might want to do so sooner rather than later: Budget threats to United States satellites that monitor the changing climate could seriously endanger the progress of their research.