Everyone’s favorite solar system — besides our own, of course — is chock full of mysteries, and apparently, water. Probably.

According to the researchers on a new study set for publication in Astronomy & Astrophysics, some of the seven discovered planets in the TRAPPIST-1 system could hold more water than what we’ve got on Earth. The European Southern Observatory (ESO) reports that based on newly discovered information about these planets, five percent of their mass may be water, which translates to “about 250 times more than Earth’s oceans.”

Though scientists announced the discovery of seven TRAPPIST-1 planets back in 2017, new observations from various telescopes, such as the SPECULOOS facility at ESO’s Paranal Observatory, NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope, and the Kepler Space Telescope have now helped scientists pinpoint the densities of these worlds. Models based on this data suggest the planets closer to their host star — an ultracool dwarf, located 40 light-years from Earth — likely have a denser atmosphere than their more distant relatives. The planets farther from their sun probably have icier surfaces, but all seven appear to be rocky, according to the researchers’ computer models.

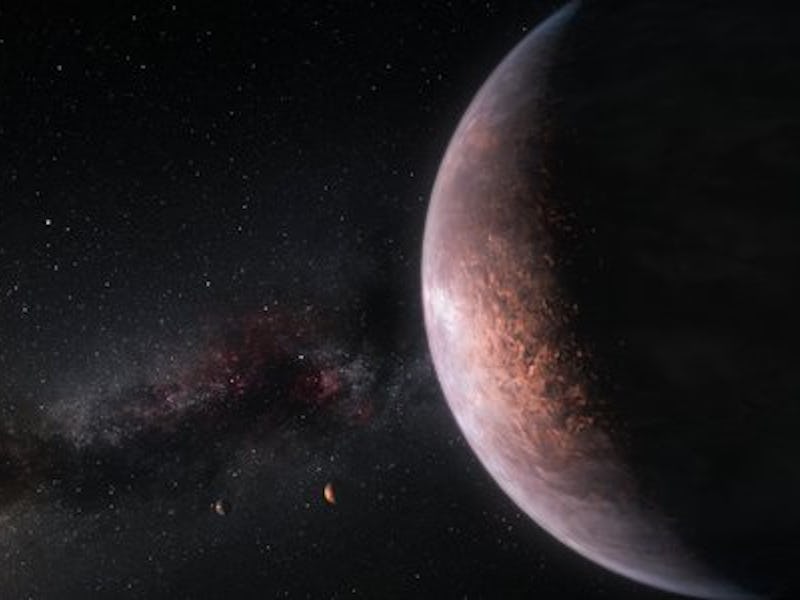

Artist's rendition of the TRAPPIST-1 planets.

The scientists on this study posit it’s possible that any of these Earth-like worlds could contain water. That said, the fourth planet out from the sun seems particularly interesting based on its size, density, and the radiation it receives from its host star.

“It seems to be the rockiest planet of the seven, and has the potential to host liquid water,” the ESO writes in a press release.

Clearly, this is an exciting development in the ongoing search for life outside Earth. It’s not a promise of E.T. or anything, but hey, it’s a nice, wholesome thing that scientists and the rest of us tinfoil hat believers can hold onto.

“Densities, while important clues to the planets’ compositions, do not say anything about habitability,” one of the study’s co-authors, Brice-Olivier Demory of the University of Bern, says in a press release. “However, our study is an important step forward as we continue to explore whether these planets could support life.”