The NBA's Heart Disease Problem Is a Race Issue, Say Doctors

Heart problems disproportionately affect African American players.

Over the past couple of years, a remarkable number of former NBA players have died from heart disease or heart attacks. Sean Rooks died of a heart attack at age 46, Moses Malone died of heart disease at age 60, Darryl Dawkins died of a heart attack at 58, and Anthony Mason died following a heart attack at age 48. The list goes on.

It’s not that these players live especially unhealthy lives after they retire. The root of the heart disease problem seems to be the physical training involved in being a basketball player, Columbia University Medical Center researchers write in a paper published Wednesday in JAMA Cardiology. Doctors in the NBA have known this for a while, but the problem is that they don’t know how to identify players that are especially at risk.

Since highly trained athletes — especially the physically large players in the NBA — experience physical changes to their hearts as a result of their intense training, it can be hard for doctors to determine whether their hearts are abnormal or simply athletic. There do exist some heart health guidelines for athletes, but in the new study, a collaboration with the NBA, the researchers report that these aren’t exactly useful for athletes in the NBA. One main problem with the existing guidelines, cardiologist Sanjay Sharma notes in an editorial commentary, is that they were not created with black athletes in mind.

Over the course of two years, NBA-affiliated physicians collected electrocardiograph (ECG) and stress echocardiogram data on 519 NBA players and draft prospects, which gave them an idea of how well each player’s heart was functioning as well as a literal picture of the heart, which was used to check for abnormalities in shape and size. The average age of the players was 24.8 years, and 78.8 percent of them were African American.

The researchers assessed the test results against three sets of currently established athlete-specific criteria for “normal” hearts. These criteria, referred to as “Seattle,” “refined,” and “international,” all have slightly different cut-offs for what count as abnormal test results.

Pooling this data, they found that 462 (89 percent) of the athletes showed physiological changes in their hearts related to athletic training. The heart health criteria, however, didn’t seem to take these heart changes into account in its guidelines for what a normal ECG should look like. As a result, the criteria suggested that a significant number of the players had abnormal ECG results — even when that wasn’t necessarily the case.

These faulty criteria make it hard for NBA doctors to identify which players actually have heart problems and which ones are simply exhibiting training-related changes.

“Despite the improved specificity of the international recommendations over previous athlete-specific ECG criteria, abnormal ECG classification rates remain high in NBA athletes,” write the study’s authors. It’s especially high in African American athletes, notes Dr. Sharma, since early heart health criteria were established with white athletes in mind.

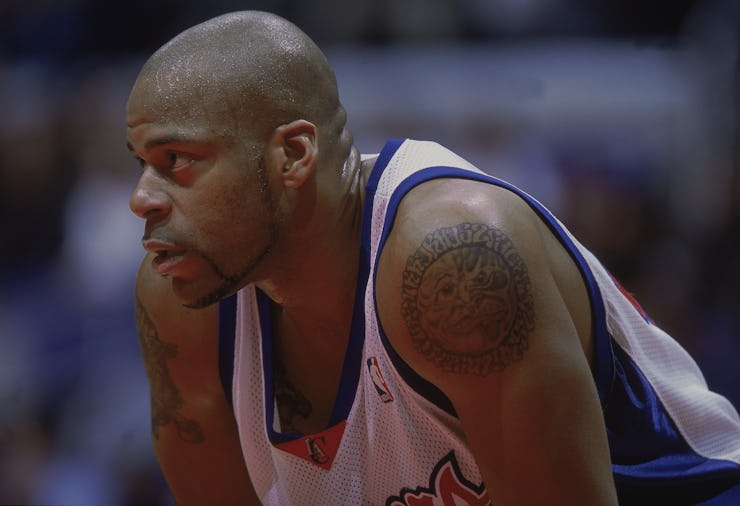

Former NBA power forward Anthony Mason died following a heart attack at age 48.

In an editorial commentary on the article also published Wednesday, Sharma says that revising heart health criteria for basketball players is especially important in light of the fact that existing criteria are way more likely to give false positives for African American athletes than for white athletes.

“Despite several modifications in ECG interpretation criteria, these findings are more frequent in black athletes than white athletes. Using the refined criteria, abnormal ECG results are reported in 11.4% of black athletes compared with 5.3% of white athletes,” he writes.

“To my knowledge, the international recommendations have never been assessed in a large cohort of black athletes before.”

Retired NBA player Moses Malone died at age 60 of heart disease.

Long story short, while many heart health factors are the same across ethnic groups, there are some minor differences in African American athletes’ hearts when compared to white athletes’ hearts that suggest these athletes should have different criteria when evaluating them for the risk of heart disease or death.

“This study is an important contribution to sports cardiology,” Sharma writes. “It emphasizes the need for more detailed investigation in larger cohorts of black athletes to … help predict more precisely which black athletes might be at risk of cardiac disease or death.”