Ancient Humans Started Drinking Wine 8,000 Years Ago, New Research Shows

Winos were slurping boozy juice much earlier than previously thought.

Today, 99.9 percent of the world’s wine owes its existence to the domestication the wild Eurasian grape. Ancient winos cultivated it in the South Caucasus region between Eastern Europe and Western Asia, which lead to the spread of wine culture to the Near East, Egypt, the Mediterranean, Europe, and eventually, the Americas.

More than a millennium of human selection and mixing of native wild vines led to the nearly 9,000 varieties of wine grapes we have today — a process that archeologists announced Monday likely began around 6,000 B.C.

In a new paper in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Science, a joint team of archaeologists from the University of Toronto and the Georgian National Museum reveal that through chemical analysis they determined that wine-making began at least 8,000 years ago during the Neolithic period.

Experts previously thought winemaking began about 5,000 BC in Iran — this announcement pushes back the emergence of winemaking by about 1,000 years at most.

During GRAPE (the Gadachrili Gora Regional Archeological Project Expedition) the archeologists excavated two Neolithic villages sites in the Republic of Georgia, where they collected fragments of ancient ceramic jars.

These jars, which are considered some of the earliest pottery found in the Near East, likely were fermentation, aging, and serving vessels. The fragments were sent off to the University of Pennsylvania, where chemical analysis confirmed the existence of tartaric acid and organic acids like malic, succinic, and citric in the jars.

A Neolithic jar possibly used for brewing wine found in Georgia.

These acids are the fingerprint compounds of grapes and wines. Their existence, combined with the archaeological data collected from the sites, confirmed to the archeologists that they had discovered the oldest example of growing grapevines with the sole purpose of producing wine.

“Our research suggests that one of the primary adaptations of the Neolithic way of life as it spread to Caucasia was viniculture,” said Stephen Batiuk, a senior research associate at the University of Toronto, in a statement. “The domestication of the grape apparently led to the emergence of a wine culture in the region.”

The Gadachrili Gora site, which was excavated.

And this culture was super into wine. Batiuk says that “as a medicine, social lubricant, mind-altering substance, and highly valued commodity” it permeated nearly all aspects of life for the Neolithic people who cultivated it, who placed it at the forefront of both business and religion. It’s believed that the Eurasian grapevine Vitis vinifera was grown abundantly around the excavation sites, in an environment that’s much like the regions of Italy and southern France where wine-grapes are famously grown today. Today Georgia, where the sites are located, still is a huge producer of wine and is home to over 500 varieties.

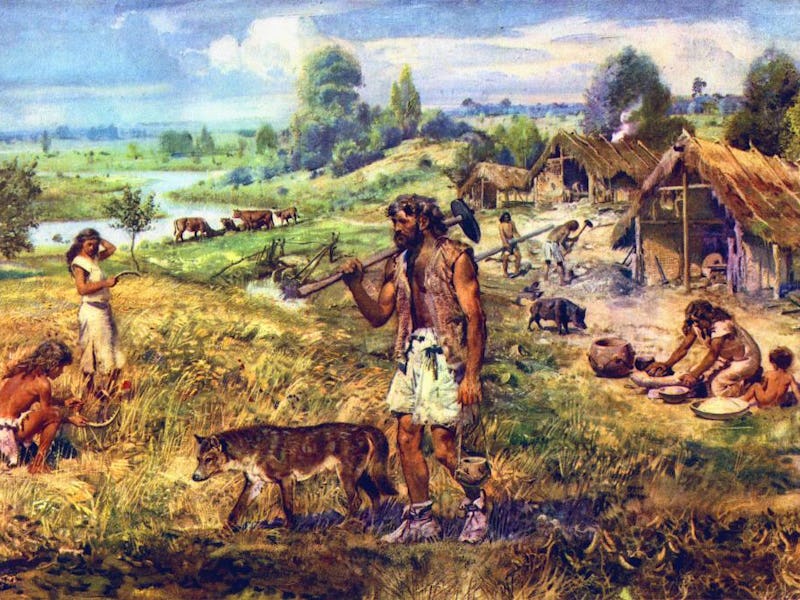

Grape-growing and wine-making fit into the larger picture of what we know about the Neolithic period, which is pegged as the time where humans first began to farm, develop crafts like pottery and weaving, and domesticate animals. Alongside the development of these practices, there was an advancement in art, technology, and culture. Today humans flock to drink White Girl Rosé at brunch — because advancement can only happen so rapidly over the course of a millennia.