The 5 Next Steps for Space Exploration After Cassini

Cassini is dead. Long live Cassini.

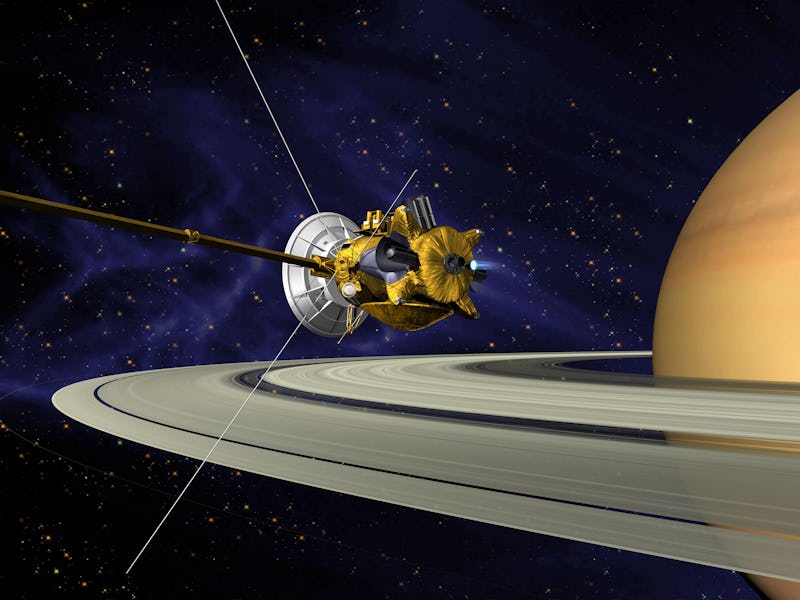

NASA’s Saturn probe Cassini is running out of the hydrazine fuel that allows it to change course and keeps its antenna facing Earth. As such, it’s about to be decommissioned after 13 years orbiting the ringed gas giant. It has entered the last two weeks of its final phase, its “Grand Finale.”

On September 15, after a distant flyby of Titan, Saturn’s largest moon, Cassini will descend into the planet itself, burning up while transmitting atmospheric data back to Earth. It will enhance our understanding of the Saturn system until the last possible second.

As with any ending, it’s only natural to look back at where you’ve been. If you could see the end of your life approaching, would you have regrets? How would you live differently, knowing what you know now? Would you do it all the same again, savoring every missed opportunity and misstep, since they made you what you are today? Or would you live differently, with less caution and more gusto, seizing every opportunity no matter how risky?

You’re not alone. In a teleconference with reporters on Tuesday, Cassini program scientist Curt Niebur, project manager Earl Maize, and project scientist Linda Spilker a shared few of their thoughts on the things they’d like to do now that Cassini is ending. Some ideas are wishful thinking for if they could do it all over again, while some are ways they’d like to expand in future missions on discoveries they made with Cassini.

Dive Into the Ring Gap Sooner

Cassini orbited Saturn for nearly 13 years before venturing into the gap between the planet and its signature rings. Only during the orbiter’s Grand Finale of weekly dives through the gap did scientists realize the truth about it. This region, which they predicted would be chaotic, turned out to be nearly empty.

“As it turned out, the dust we thought was [between rings and Saturn] was remarkably missing and we were able to relax our shielding,” Maize told reporters. “Given how benign this environment is, it’s something we could have jumped into much sooner in the mission. Now that we know, it’s a place we’d be very happy to spend more time.”

Explore Enceladus and Titan

In 2005, during Cassini’s earliest days, it sent the Huygens probe down to Saturn’s largest moon, Titan. There, Huygens captured video of Titan, showing humans a landscape shaped by flowing methane, littered with “rocks” of solid water. In April 2017, Cassini flew through the geyser at the south pole of the icy moon of Enceladus, where it detected molecular hydrogen, evidence of possible microbial life. These findings were just a sampling of the possible experiments to conduct on these moons, so it makes sense that the scientists would want to get another taste.

“If I could do another flagship, I’d want to go back,” said Spilker. “To explore Enceladus and Titan and do a Saturn probe. With modern instruments.”

Probe Saturn With Modern Instruments

That brings us to the next item on the Cassini Project Wish List: modern instruments. Launched in 1997, Cassini sported what was then state-of-the-art technology. But the art has changed a lot since. If they could do another Cassini mission, the scientists involved would update the tech and add a probe they could send into Saturn without ending the whole mission.

Send Probes to Uranus and Neptune

And while we’re sending probes to Saturn, why not Uranus and Neptune, too? Only Voyager 2 has ever visited the solar system’s most distant planets, and then only for brief flybys. A more extended stay at either planet would be a first.

“I’d send a pair of Cassini-like orbiters to Uranus and Neptune,” Spilker told reporters. “Sure, there’s a whole lot of stuff left to discover about the Saturn system, but it’s just one small part of our cosmic neighborhood.

“We can’t ignore the rest of the solar system,” said Maize. “It’s just too compelling.”

Find Out How Long a Day Lasts on Saturn

That being said, there’s still some information about Saturn that Cassini couldn’t tell us. Since Saturn’s magnetic pole and rotational axis are less than one degree apart, scientists haven’t been able to figure out the planet’s rotational period, meaning we don’t actually know how long a Saturn day is. This may seem basic, but it could remain an open question after Cassini’s gone. It could be a little while before we get another chance to answer it.

In the end, though, you can’t look back with too many regrets on a life well-lived. As Cassini prepares to plunge into Saturn, the scientists that worked on the project are satisfied with the more than 4,000 academic papers that Cassini’s data supported.

“It couldn’t be better. We have had exceptional performance and we couldn’t have asked for more,” said Maize. “It has been a phenomenal ride.”